TOWARDS AN ECONOMIC REVOLUTION: A COGENT PERSPECTIVE ON THE FINANCIAL SERVICES SECTOR TRANSFORMATION.

A discussion of this nature requires frankness and openness and should be premised on the understanding that real and genuine transformation of South Africa’s economy will not come through substituting white capitalists with black capitalists who continue to treat the majority of our people as nothing but suppliers of cheap and easily disposable labour or as fodder for exploitative credit. It is overdue because 23 years since the end of legislated racism, the economic and social marginalisation and impoverishment if not exclusion of the black majority persisted and been reproduced.

In summary, this perspective focuses on the financial services sector and cogently proposes that since economic exclusion of the black majority was first a colonial conquest and more practically a legislated reality, economic inclusion should be legislated and enforced into reality as well.

South Africa needs to pass enforceable legislations and laws that will guarantee black economic ownership and control, largely due to the reality that the sunset clauses, laws and agreements that were cobbled up in the early 1990s, and the ways in which they have been implemented in practice, have failed dismally to transform South Africa’s economy.

Enforceable economic legislation is the most correct way of beginning to achieve economic inclusion because the record of social contracts and compacts aimed at achieving black ownership and control of the economy have failed dismally for the vast majority while enriching a black elite to be found across both the economic and political domains.

This perspective of the imperative of major transformation of finance, and the economy and society more generally, is one of the most important contributions within South Africa’s political economic discourse, and should therefore not be viewed through narrow political partisan telescopes, which often re-affirm the class composition of current South Africa’s economic ownership, and control. This is an important contribution because it moves from the premise that the black majority and particularly Africans should never be apologetic in their quest of owning and controlling South Africa’s wealth and economy in a manner that is proportionate to their population size, if not more.

Section 9(2) of South Africa’s Constitution says, “Equality includes the full and equal enjoyment of all rights and freedoms. To promote the achievement of equality, LEGISLATIVE and other measures designed to protect or advance persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination MAY BE TAKEN”. The perspective adopted here is that to promote the achievement of equality, LEGISLATIVE and other measures designed to protect or advance persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination MUST BE TAKEN.

Financial sector

The financial sector is one of the most important sectors in South Africa’s economy and includes the banks, the insurance companies, and investment funds, which play a critical role in the economic life of our country. Any economic transformation programme that overlooks the financial sector will dismally fail because the reality is that while South Africa’s economy base is what is correctly characterised as a minerals-energy-complex, it has since the end of apartheid been highly financialised. The period post-1994 witnessed massive financialisation of the South African economy, which means the country’s economy is now appropriately characterised as the minerals-energy-finance complex.

From the perspective of transformation for the majority, the Financial Services sector remains little different than it would have been under a continuing apartheid. It is a sector, nevertheless, that is perceived to have massively increased its contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) in the period post-1994, in light of the growth of financial services. Despite the financial sector’s qualitative and quantitative expansion in the post 1994 period, it is largely reflective of the colonial-cum-apartheid past, and its racial composition would have been the same even if it expanded pre-1994.

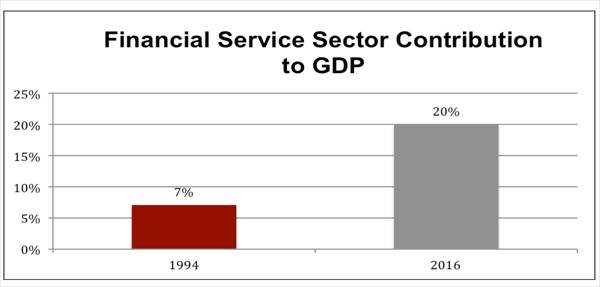

In 1994, Financial Services sector contributed 7% to the total GDP, in 2016 the share of Financial Services sector to GDP has increased to 20% making it the highest contributor to GDP followed by Trade and Government both contributing 17% (See diagram 1). According to the 2015/2016 World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Survey South Africa is ranked 8th in Financial Sector Development, out of 140 countries.

Figure 1: Financial Services sector contribution to GDP comparison between 1994 and 2016 – Source: StatsSA

BANKS

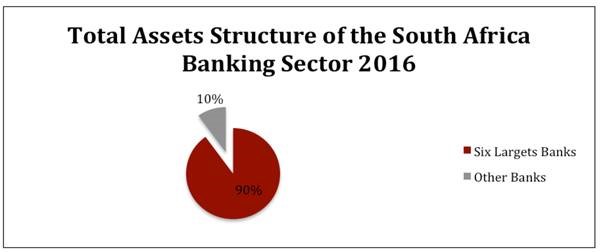

At the core of the financial services sector are banks. Banking and banks in South Africa are dominated by the big six largest banks i.e. Barclays Africa Group (also known as Absa), FirstRand (FNB and Wesbank), Nedbank, Standard Bank, Investec and Capitec which constitute more than 90% of the total market share with total assets of R4.8-trillion by the end of 2016 (See figure 2).

Figure 2: Total assets structure of the South Africa Banking Sector – Source South African

Reserve Bank

The level and extent of black ownership in the banking industry has collapsed to around 1% from 10% in the last four years due to sell-off of black economic empowerment stakes in major banks by black investors if we put aside institutional investors such as the Public Investment Corporation (PIC). The only arguably black owned bank accounted for just 1% of total assets.

Note: if we consider that UBank is the only wholly black-owned bank.

There are of course mutual banks such as the not so wise, but scheming, Venda Building Society (VBS) Bank, whose asset value and significance in the banking sector is inconsequential. VBS and some of the mutual banks owned by the Government Employees Pension Fund (GEPF) are not systemically important financial institutions (SIFI), and their discontinuation will not affect South Africa’s economy in the same way the huge banks and insurance companies do.

Banks can be very important instruments and vehicles in driving socio-economic development and meaningful industrialisation that will lead to inclusive growth but they can also be speculative and parasitical as is the overwhelming case in South Africa to the extreme, as well as elsewhere is the world as has become apparent in the light of the Global Financial Crisis and the responses to it. Without control of the banking systems and banks, real economic inclusion through industrial expansion and social development will not be possible.

Banks play a central role in people’s access to land, education, housing, cars, food, clothing, and many other essential services, as well as in their relations to government. Banks run and control many people’s lives. Just 450 multinational companies dominate the world economy of which 300 are financial companies.

While the big business of finance takes place beyond the reach of the ordinary citizen, black or white, its scope and influence also reach into daily lives not only in setting the trajectory of the economy but also in dependence on credit to meet consumer and other needs.

So, in addition to lack of transformation in the past 20 years, banks continue to use race as a mechanism of granting black people access to mortgage and other forms of finances, not only reproducing and keeping alive economic apartheid but using access to credit to shape human settlement spatial patterns in terms of access to properties, facilities, education and lifestyle choices. Banks and South Africa’s financial system place almost all black people in debt and have designed a cartel-like system that makes it impossible for black people to own valuable property, yet gives cheaper and easily accessible credit for perishable goods.

Insurance companies

By the end of December 2015, the market capitalisation of the JSE-listed insurance sector securities was R517.3-billion. The majority of insurance policyholders, particularly short-term funeral policies and vehicle insurance, are black people in South Africa, yet licence conditions, high audits and actuarial fees, excessively demanding standards and a heavy regulatory burden excludes black players in the market. There are very few black-owned and controlled insurance companies in South Africa (includes Workers’ Life, Bophelo Life, Union Life, and Nestlife) and they account for less than 1% of the insurance industry.

Top biggest insurers i.e. Santam, Hollard and Old Mutual account for more than 45% of the market share. Existing legislation had not facilitated black participation in the insurance industry. Hence Parliament cannot just pass legislation dealing with compliance only but it must prioritise transformation, and inclusion of black people in the insurance space. Insurance companies and funds must be designed in a way that should benefit policyholders in the short term in a meaningful way.

The exclusion of blacks from benefiting from the insurance industry is not only at ownership level but also in downstream opportunities. The short-term insurance industry is worth approximately R95-billion a year in terms of procurement of which only R1.5-billion a year goes to black tow truckers and small-scale panel beaters and contracts. Otherwise, black people do not benefit from the insurance business as it is predominantly white-owned and controlled. The cost of acquiring an insurance licence in South Africa is also prohibitive, and there exists no mechanism to facilitate meaningful participation of black companies.

Asset managers

Pension fund assets management is collection and investment of pension monies on behalf of workers to ensure financial security of pension plans benefits, to ensure that when employees retire, there is sufficient money available for regular payment. For example, the Public Investment Corporation (PIC), a wholly South African government owned asset management company, invests pension, provident, social security and guardian funds collected through Government Employees Pension Funds in diversified class of assets from listed equities, capital marketed, money markets and properties. To date, the PIC has assets work more than R1.6-trillion.

In the private sector, there are predominantly white-controlled asset management companies of various pension funds. The recent BEE.conomics report issued by 27 four Investment Managers illustrates that by September 2016, Assets Under Management by South African Asset Management companies are R8.9-trillion, and assets managed by black assets managers are R408.3-billion, just under 5% of the total value assets.

Most of these asset management companies are linked to the big banks and financial conglomerates such as Investec, Standard Bank, Absa, Nedbank, etc. These asset management companies belong to an organisation called the Association of Savings & Investments South Africa (ASISA), which says in its self-description that “ASISA operates as a non-profit company and is empowered by a mandate from an industry that manages assets of nearly R8.6-trillion (as at December 31, 2015)”. This figure appears astounding, particularly when viewed from the reality that South Africa’s GDP stands at R4.2-trillion, but this will be explained from a different perspective.

In March 2017, Business Day quoted a representative of Alexander Forbes who says, “None of the top 10 asset managers are black-owned”. The Business Day article illustrates that, “The top 10 managers at June 2016, ranked in order of total assets under management, were: Old Mutual Investment Group, Coronation, Investec Asset Management, Allan Gray, Sanlam Investment Management, Stanlib, Investment Solutions, Prudential, Futuregrowth and Sanlam Multi-Manager International”.

Interestingly, the Business Day article further notes that, “While 68% of SA’s asset management firms held a Level 1 or 2 broad-based black economic empowerment (B-BBEE) rating, this did not equate to adequate transformation”. This reveals the fact that B-BBEE legislation and codes of good practice are weak instruments to guarantee and ensure meaningful participation of black people in the economy.

A view that argues that black people are incapable of asset management does not hold water. The government owned asset management company, PIC, is managed by black people, and is one of the best asset managers in the world, and yet the private asset management in South Africa is more than 90% white owned and controlled. The inclusion of black people into meaningful and massive asset management will not be a voluntary contribution of the existing structure; it must be legislated into law.

Stock exchange

Johannesburg Stock Exchange is currently ranked the 19th largest stock exchange in the world by market capitalisation and the largest exchange on the African continent with almost 400 companies listed including some of the world biggest such as British American Tobacco, Glencore Xstrata and BHP Billiton. However, more than 20 years into democracy, it is estimated that blacks only own 10% of the market capitalisation mainly through government employees pension fund PIC. Without considering the PIC, the figure drops drastically to an estimate of 3%.

At the current rate of transformation of the JSE, with blacks only owning 10% of the market capitalisation, it will take more than 80 years to get to a desirable minimum of 50% black ownership of the JSE market capitalisation, and another 50 years to get more than 80% which is a true demographic reflection of who should have control over the economic interests of South Africa. As a result, blacks own or have direct influence just over a R1-trillion of more than R13-trillion invested in the JSE.

The hidden history of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) is that for a very long time under colonial and apartheid governments, black people were not allowed to own shares in the Securities Exchange. The scars of systematic economic exclusion still haunt South Africa in the JSE’s main board because none of the Top 50 companies is wholly or majority black owned and controlled. These are vestiges of apartheid economic exclusion which can only be reversed through decisive and enforceable legislation.

Observations

Now, these realities reveal a sordid and certainly insupportable reality that South Africa’s economic resources will never be transferred to the majority of the people, or deployed for their benefit, unless decisive steps and actions are taken to address these crises of economic racial inequalities in the financial sector. White owners of the economy reproduce themselves alongside racial lines, and this system of racial exclusivity in terms of ownership and control of key sectors of the economy was legislated into reality by the colonial and apartheid governments. It has only been modified, not least through finance itself, through the marginal inclusion of a small black elite.

If the pace of economic transformation continues its current path, racial inequality and white economic supremacy will remain a vivid reality in South Africa even when all people who are currently alive in 2017 are no longer with us. If anyone doubts this, just consider the reality that all people who were alive in the 19th century when diamonds and gold were discovered and black people were excluded from economic ownership and forced into waged labour by the Chamber of Mines are no longer alive, but the system established then is still representative of South Africa’s present reality. Young adults of 20 years or so of age will not have experienced apartheid directly but this is no reason to overlook its continuing impact.

In this light, the current Black Economic Empowerment discourse and policies are a diversion from the real foundation of ownership for and by black people. The convulsion of black ownership of the economy to include issues that had be to separated into BEE compliance only provided an escape clause for white-owned and controlled companies to continue as such. There are so many white owned companies in South Africa that are Level 1 or Level 2 B-BBEE compliant. As if that is not horrible enough, more than 40 of the 50 B-BBEE Verification companies are white-owned and controlled.

Black economic ownership has been drowned under a load of requirements which could be legislated separately from genuine economic empowerment of black people. The clarion call is made here for a Black Economic Ownership Act, which should strictly speak to the extent and quantity of black ownership of each industry and economic sector, and these other B-BBEE aspects treated importantly but in a separate legislation.

A BEO Act should define the content of black ownership, placing workers and communities at the centre and guaranteeing a minimum of 50% participation by women in all ownership schemes. This will help in avoiding the challenge of substituting white with black capitalists. Those who wish to be black capitalists must not staff-ride businesses, but must venture into real wealth creation and expansion of the productive forces.

What is to be done?

South Africa needs to introduce three categories of enforceable legislation, and one major onstitutional change. It is important to highlight the importance and centrality of legislation because of the correct emphasis by Blackstone, Sanders and Parekh in a book, Race Relations in Britain, in arguing that,

“Legislation alone cannot create relations or change attitudes. But it can set clear standards of acceptable behaviour and provide redress for those who have suffered in the hands of others. If law can play a repressive role by sanctioning racial segregation and discrimination as it has done in Nazi Germany, the American South, Rhodesia and South Africa, it can operate with equal force in the opposite direction by declaring that, equality of opportunity, regardless of race or colour, is to be pursued as a major social objective. It is a statement of public policy by Parliament intended to influence public opinion.”

Unsurprisingly, once the situation of political power has changed, those that benefitted under apartheid, and have inherited those advantages, not least through the racist legislation and policies of the past, are all too ready to proclaim by appeal to the principle of sanctity of private property and market principles and the like, that similar interventions to favour the disadvantaged are inappropriate, unjust and inefficient even for those it is intended to benefit. It is on this basis that South Africa should pass economic legislation to redress the balance. These are the laws that should be considered as part of this programme. Section 9(2) of South Africa’s Constitution says,

“Equality includes the full and equal enjoyment of all rights and freedoms. To promote the achievement of equality, LEGISLATIVE and other measures designed to protect or advance persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination MAY BE TAKEN”.

1. Laws for economic inclusion to share in current patterns of ownership.

The BEE Charters tried to achieve black inclusion into existing economic interest but they were not enforced and therefore meaningless. Therefore, legislation should be passed by Parliament that prescribes that all legal businesses in SA must be a minimum of 50% owned by black people or the State, and content of such ownership must not be black male elites. The content of black ownership must include workers, communities and must always be gender balanced. Gender inclusion in all economic platforms must not be a “by the way” aspect of transformation, but should underpin all forms of economic ownership and control.

It is important to highlight State ownership in certain sectors, and collective ownership in others, because the Reserve Bank, the mines and other strategic sectors of the economy must have at least 51% of State ownership. The Reserve Bank model of limitation of shares held by one person and their associates could still apply to the remainder of the shares, whilst 51% is under direct State ownership and control.

A separate wholly owned State bank should exist to serve as a means to guarantee the majority’s access to cheaper financial services, mortgage, vehicle and enterprise finance and many other essential financial services. State-owned banks have played an important role in the economies that had to catch up with the first industrialisers in the world. This is essential and articulated cogently in the Founding Manifesto of the Economic Freedom Fighters, which carries the most clear vision on what should constitute economic transformation in South Africa.

It must be highlighted that the proposed economic inclusion legislations should be decidedly dissimilar from the set of BEE Laws and Charters that had no meaning to different industries. The new set of legislations to guarantee economic inclusion must be enforceable laws with consequences for those that try to operate outside the law. The new set of laws should place black economic ownership at the centre of the economic transformation programme.

2. Laws about set-asides

The principle about set-asides is that if 100 Insurance licences are going to be issued, 60 must be given to local black South African insurance companies. We need new legislation that will facilitate black participation in the economy, not as minority shareholders in established companies of white people. BBEEE and the so-called black empowerment laws in South Africa since 1994 have largely been about staff-riding few black male elites into established white companies, who often fall off to be replaced by new politically relevant male elites in the future.

The reality of black economic staff riding is reflected in the fact that there is no massive black-owned corporation in South Africa, even if a list of the Top 100 were to be produced. The late attempts to produce black role players in the economy through the so-called black industrialist programme is laughable, with only R500-million allocated to produce 100 black industrialists. Those who understand the nature and scope of South Africa’s economy will know that such an approach and allocation will not achieve anything meaningful.

3. Reform Procurement Legislation

Currently, the majority political party in South Africa’s Parliament has an election manifesto that commits to ensuring that a minimum of 70% of goods it consumes are locally produced. The only political party that advocates for real economic inclusion in SA’s Parliament, the EFF, advocates localisation and extends this principle and practice to the private sector’s sourcing of consumable goods for retail purposes. This must be law and must be included in the PFMA and MFMA. Companies that provide goods and services to the State must be a minimum of 70% local-owned and 50% black-owned.

This will create a solid platform for the creation of new wealth because the current economic system only provides for the importation of so many finished goods and products. As a matter of fact, South Africa’s top 10 exports to its biggest trading partner, China, are raw and semi-processed natural and mineral resources, while the top 10 imports from China are finished goods and products. A sophisticated trade and investment policy can be developed to achieve this without upsetting forces of globalisation (neoliberalism).

The economic exclusion of black people in South Africa was legislated, and its atavistic remnants are still vivid, and the only way to reverse these is legislative. Social consensus on issues that relate to economic interests does not work. Capitalists do not go around making friends for the sake of it, they make friends for the sake of profits and always seek to adapt to new legislative and material conditions to continue making profits. That is why capitalists always seek to influence and control political power because they know political power can sustain their narrow class interests.

Of course, there are attempts to legislate transformation like in MPRDA legislation, which prescribe the minimum targets of ownership and procurement and enterprise development to enable meaningful economic participation and contribute towards creation of sustainable black owned business. The legislation, particularly the amendments to the MPRDA, also places obligations on producers of minerals to offer a percentage of minerals or form of petroleum resources for local beneficiations and subjecting of granting of mining or fishing licences to compliance with industry respective charters dealing in social and labour plans.

These kinds of legislation must have teeth and enforceability to the extent that those who do not comply with them or cheat the requirement of black ownership must be discontinued from operation or expropriated without compensation. Eggshell-walking around issues of real economic revolution will only serve to preserve the status quo and should not be an option. Black people must stop being apologetic on black ownership and control of the economy.

Such legislation is an important foundation and is legitimate because the Constitution commits to redress and equity. As said above, Section 9 (2) says, Equality includes the full and equal enjoyment of all rights and freedoms. To promote the achievement of equality, LEGISLATIVE and other measures designed to protect or advance persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination MAY BE TAKEN”.

The constitutional changes are long overdue as is removal of the compensation requirement for land restitution and redistribution. Without land, there is no economic policy that will survive. The proposed legislative interventions will be meaningless if the land remains in private hands. The State should take custodianship of all land in the same manner as it is a custodian of all mineral resources, and the necessary political consensus should be relatively easier to achieve because black political parties that can hold to this view have the required majority to amend the Constitution.

The current economic inclusion policies have proven very weak in principle and practice. BBBEE Codes just provide for black people to be indebted economic staff riders, who borrow money from the banks, buy shares and do not genuinely participate in many economic activities in a meaningful sense. Majority or all of the BEE beneficiaries are staff riders in white companies and do not even know how the companies are run.

Conclusion

We need a radical economic revolution programme premised on the consensus of all political parties in South Africa. This contribution serves as a very important foundation for thorough political deliberations on how we should all strive to include black people into the economy. We carry individual and collective responsibility and obligation to undo the economic justices of the past and to build equitable economic and social development for the future. This needs dedicated focus and commitment to succeed. The argument made here is that legislation and other measures designed to protect or advance persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination MUST BE TAKEN.

Floyd Shivambu is Deputy President of the Economic Freedom Fighters. This article first appeared on his weblog and in the Daily Maverick.