The Chinese Financial System and Global Economic Stability III

The Silk Road Project

The Silk Road – does it not conjure up images of famous and exotic exploits? The travels of Marco Polo from 1271 to 1295 with a land crossing from Venice to Beijing and a sea passage for much of the way back, are recorded in his Travels.

On a much larger scale, the great Chinese admiral, Zheng He, commanded seven great naval expeditions between 1405 and 1433, visiting Brunei, Java, Thailand, Southeast Asia, India, the Horn of Africa and Arabia. His first expedition consisted of 317 ships, holding almost 28 000 crew, making the voyages of Vasco da Gama and Christopher Columbus look provincial by comparison.

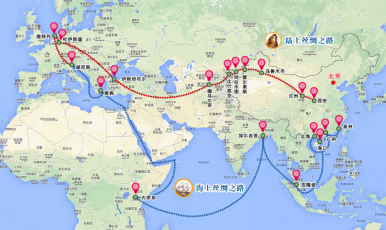

The Chinese government released in May 2014 the map below indicating the extent of a New Silk Road vision. This map is reproduced below. There is a land based road and a sea based road. The land base road stretches across China, through Central Asia, to northern Iran, Syria and Turkey. From the Bosporus Strait it runs northwest through Europe to Germany and the Netherlands and then south to Venice.

The sea based road links Chinese provinces, heads towards the Malacca Strait, then to Kolkata and on to the Kenyan coast, before turning north round the Horn of Africa to Athens and Venice. Together with internal Chinese land routes, the circuit of the two roads together is complete.

In March 2015, the Ministries of Commerce and Foreign Affairs released a document entitled Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Belt and Road.

What does China hope to achieve?

Its 2015 document puts the matter thus:

Countries should work in concert and move towards the objectives of mutual benefit and common security. To be specific, they need to improve the region’s infrastructure, and put in place a secure and efficient network of land, sea and air passages, lifting their connectivity to a higher level; further enhance trade and investment facilitation, establish a network of free trade areas that meet high standards, maintain closer economic ties, and deepen political trust; enhance cultural exchanges; encourage different civilizations to learn from each other and flourish together; and promote mutual understanding, peace and friendship among people of all countries.

The New Silk Road is a broad outline of goals, being filled in with projects as they are developed, and as negotiations with target countries allow. The NSR is not a start-up from scratch, but builds upon and extends a number of existing projects.

In pursuit of NSR goals, President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang have visited over twenty countries, and signed memoranda of understanding with some of them. It has launched the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank with 52 participating countries and an initial capital of US $ 100 billion, and a US $ 40 billion Silk Road Fund. It is also reinforcing the investment function of the China-Eurasia Economic Co-operation Fund.

What’s in it for China?

Diversification of its huge foreign assets. China has an estimated US $4 trillion of foreign reserves[1]. In May 2015, China owned US $ 1 270 billion of US Treasury securities, more than any other country, though Japan comes a close second. Related is the use of spare capacity in Chinese industry, built up by decades of massive investment.

Development, via the land route, of its poorer and sparsely populated northern and western provinces. China can be divided by a straight line (the Hu Huanyong line) running from Aihui in the north east to Tengchong in the south west. The 2010 census indicated that 94% of the population lived to the south and east of the line. To the north and west lie Xingjiang, Tibet, Qinghai and Ningxia provinces, most of Inner Mongolia and Gansu provinces and part of Sichuan. Under this head can be included the development of more eirenic relations following culturally based strife between Tibet, Xingjiang and the rest of China.

Development of stronger economic ties with Russia’s Asian land mass. There are gains from a strong comparative advantage, with Russia having the advantage in resources and China in technology. China has been taking advantage of recent tensions over Ukraine between the US and Europe, on the one hand, and Russia, on the other.

Development of stronger economic ties with Europe, drawing in resources from the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. There will be attractive opportunities for European investment in Central Asia, but tension in southeastern Europe will need to be lowered if these are to be fully realized.

Projection of geopolitical influence. This will be a long and subtle game. It has to negotiate several obstacles:

Competition with Russia for influence in central Asia;

Negotiation of divisions along the land road, especially the tensions between India and Pakistan, and between Sunni and Shia Islam. In the case of India, there is historical baggage to be overcome: unresolved border disputes, India’s close relationship with the US and Japan, the implications of China’s growing relationships with Japan. On the other hand, India and China are both involved in the BRICS Development Bank. None of the obstacles are insurmountable, but they will not be removed overnight;

The mess in the Middle East;

Counter moves by the United States to contain Chinese influence.

What are the risks?

Overextension. A project such as this requires the overcoming of externalities – social costs inhibiting market-led growth. Given very long lines and a piecemeal approach, connecting up the elements will not be easy. Cost and breaks in the circular road may push costs up and profitability down to unsustainable levels.

Possible emerging weaknesses in the Chinese economy. On this, see the first and second briefs in this series.

A long standing Chinese oscillation between engagement with the rest of the world and introversion. After the end of Zheng He’s seventh expedition, during which he probably died, the fleet was broken up. Nothing like it was to occur in later Chinese history.

***

The Chinese Financial System and Global Economic Stability IV

The Chinese-South African Economic Relationship

South Africa’s economic relationship with China can be summed up under three headings: trade, asset holdings in each other’s economies and China’s economic interest in South Africa.

1. Trade

The table below sets outs the fundamentals of South African merchandise trade with China since 2010:

|

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015* |

|

SA exports to China (US$ million) |

8 065 |

12 507 |

10 316 |

12 059 |

8 758 |

|

|

SA imports from China (US$ million) |

11 458 |

14 222 |

14 612 |

16 007 |

15 457 |

|

|

Exchange rate (Rand per yuan) |

1.08 |

1.12 |

1.30 |

1.57 |

1.76 |

2.01 |

|

IMF Metals dollar price index (2005=100) |

202 |

230 |

191 |

183 |

164 |

136 |

Notes: Data from the South African Revenue Services, the Reserve Bank’s Quarterly Bulletin and the IMF. The 2015 exchange rate refers to the position on 17 August and the metals price index to the second quarter.

The Rand has depreciated by nearly half against the yuan in the last five years. The dollar value of exports to China will depend on commodity prices, particularly metal prices. Just over two-thirds of South African exports fell into the single category of ‘mineral products’ in 2014. The current severe ‘commodity bust’ is the single most important factor currently in the evolution of SA exports to China. There may be a modest further depreciation of the yuan and some slowing in China’s growth, which influence our exports in opposite directions. The IMF’s economic outlook project China’s growth in 2016 at 6.3%, compared with 6.8% in 2015 and 7.4% in 2014.

On the other hand, imports from China will depend on South African economic growth and the rand-yuan exchange rate. Nearly all our imports consist of industrial inputs and final manufactured goods. Just under half consisted of machinery, which has become considerably more expensive in rand terms.

2. Asset Holdings

The pattern may be summarised as follows:

South African liabilities and assets in relation to China mainly take the form of direct investment. Portfolio investment both ways is very low and financial holdings each way are roughly similar;

South Africa assets in China greatly exceed Chinese assets in South Africa. Moreover, South African assets in China have been growing fast. In dollar terms, the value of Chinese assets in South Africa flat-lined at about US $7.5 billion between 2011 and 2013, while South African assets in China have risen from US $ 16 billion to US $ 46 billion over the same period. At this level, we have a greater stake in the Chinese economy than they have in ours.

3. China’s economic interest in South Africa

Some have sought to discover a ‘Beijing economic consensus’ as a counterpart to the ‘Washington economic consensus’. They have searched in vain: such a contrast betrays Cold War thinking, of which the Washington consensus, now obsolete, was the last enchantment. We are now in a diplomatic world akin to the nineteenth century, where countries have permanent interests, but not permanent friends. In the context of China-South African relations, fraternal greetings between the communist parties in the two countries may be part of diplomatic politesse, but they count for nothing in relation to economic interests.

Chinese economic interests in South Africa have two main components:

Minerals, especially those in which South Africa has a large share in known international reserves. The facts of geology are constant, but knowledge of it increases and known reserves increase. Moreover, exploitable resources change with economic circumstances. For now, the current travails in the mining industry which make it inefficient are not in Chinese interests.

Financial, in so far as South Africa opens up financial relations with sub-Saharan Africa. Hence the acquisition of a stake in Standard Bank. But China is pursuing other opportunities in other countries, and will adjust its stakes in line with performance. South Africa either delivers, or it will be outflanked.

R W Johnson is right to observe that the current fecklessness in South African economic policy - graced as the intensified second phase of the first stage of the national democratic revolution – is creating its nemesis in the form of structural adjustment down the line.

The ever greater search for rents, the hollowing out of state owned corporations and public institutions, deterioration in indices of corruption and undermining of property rights essential to support production – and all this, when the warning lights on the South African economic dashboard are lighting up – is creating a mess which is not in Chinese interests.

They will not bail such a configuration out, either through the BRICS bank, or in any other way. Instead, they will join a growing international movement in support of South Africa policy reform. To suppose otherwise will mean joining the tradition of the Melanesian cargo cult of the late nineteenth century, with as little prospect of success.

Charles Simkins is Senior Researcher at the Helen Suzman Foundation.

This article first appeared as an HSF Brief.

Footnote:

[1] The Financial Times of 16 August reports a current total of US $3.65 trillion and that US $315 billion has been used in the last twelve months of capital flight .