Minister Blade Nzimande’s remarks in the portfolio committee for higher education and training on Stellenbosch University (SU)

3 September 2015

Background

The commitment of the democratic government is to transform higher education, thus a range of initiatives seeking to effect institutional change are introduced into the system. These include the restructuring of higher education landscape and institutions; new policies; new funding formula; the remodelling of institutional governance; and the enactment of new laws and regulations.

The White Paper 3: A Framework for the Transformation of Higher Education (1997) seeks to guide programmes and processes aimed at transforming the post-apartheid education system, with a vision of a transformed, democratic, non-racial and non-sexist higher education system that will “support a democratic ethos and a culture of human rights by educational programmes and practices conducive to critical discourse and creative thinking, cultural tolerance, and a common commitment to a humane, non-racist and non-sexist social order”.

There has been marked progress following the collapse of apartheid in that rigid racially exclusive universities no longer exist. It is a reality, however, that some of the historically white institutions remain inherently conservative and resistant to change. Racism, sexism and class discrimination continue to manifest themselves in the core activities of teaching, learning and research, as well as in the social activities and spaces of the institutions.

In his assessment, Badat observes that “Institutional cultures at historically white institutions may, in differing ways and to varying degrees, compromise equity of opportunity and outcomes. The specific histories of these institutions, lingering racist and sexist conduct, the overwhelming predominance of white academics and administrators and male academics, the under-representation of black and women academics and role-models, and the continuing challenge of appreciating diversity and difference could all combine to reproduce institutional cultures that are experienced by black, women, and working class and rural poor students as alienating and exclusionary” (Badat, 2010).

Despite the policies and programmes designed by institutions to address issues of transformation, some of the practices are persistent. There is still a need for institutions to create an enabling environment and an institutional culture which is welcoming to all; embodies the values of democracy; affirms diversity; and uproots deep-seated racism and sexism that create barriers to meaningful participation in learning and campus life.

Language Policy

Language is critical to higher education transformation as it impacts on institutional culture, access and success. “The challenge facing higher education is to ensure the simultaneous development of a multilingual environment in which all our languages are developed as academic/scientific languages, while at the same time ensuring that the existing languages of instruction do not serve as a barrier to access and success.” (section 6: Language Policy for Higher Education)

In November 2002 the Language Policy for Higher Education was promulgated. Its main aim is to promote multilingualism in the institutional policies and practices of individual institutions of higher learning. The Language Policy acknowledges the linguistic diversity of university student populations; points to the declining enrolments in language programmes; and mentions that there are limited African language training requirements in university programmes. The policy:

-highlights the need to promote South African languages for use in instruction in higher education and the need to develop strategies for promoting proficiency in languages of tuition;

-recognises the retention of Afrikaans as a language of the academy, while supporting different strategies, including dual and parallel medium approaches, to ensure equity and diversity;

-recognises the need to build South African languages and literature and commits the Ministry, through planning and funding incentives, to encourage the development of programmes for South African languages;

-recognises the cost of doing so in relation to overall student numbers and proposes regional collaboration frameworks;

-encourages the development and study of foreign languages, particularly those that are important for the country’s cultural, trade and diplomatic relations.

-encourages all institutions to consider ways of promoting multilingualism and requires institutions to indicate in their plans what strategies have been put in place, and

-requires institutions to develop their own language policies.

The Stellenbosch University policy states that the institution regards all official South African languages as assets and they should be used to develop the human potential of the country. Against this principle the institution is committed to contribute to the development of Afrikaans as an academic language together with English and isiXhosa. Inclusivity is advanced specifically by using Afrikaans and English in teaching and engagement.

The following are the different language options for students at SU in the teaching context:

-parallel medium (class group is divided into two streams, one Afrikaans and one English)

-Educational interpreting between Afrikaans and English

-double medium (Afrikaans and English are used in the same class)

-Only Afrikaans or only English (in a minority of cases)

Study materials such as module frameworks, study guides, assessment assignments (e.g. tests) are offered in Afrikaans and English. The mixed language model produces graduates who understand and are able to function in the multilingual context. The policy also states that the institution recognizes the importance of isiXhosa as a local (social) language and as a developing academic language and intends, within the limitations of what is possible to contribute to its development.

While the Language Policy may comply with the requirements of equity under section 29 of the South African Constitution, the issues that the students are raising cannot be ignored. Despite having good policies, we have observed that many institutions seem to struggle to build a sense of social cohesion in which all members feel equally valued.

The Constitution does not prohibit any university from teaching students in Afrikaans, however, the language must not be used to exclude non-Afrikaans speakers or deprive them from quality teaching and learning. As articulated in the Departmental Language Policy for Higher Education, Afrikaans as a language of scholarship and science is a national resource and must therefore be retained as a medium of academic expression and communication in higher education. However, it cannot be used as a basis for the advancement of racial separation.

Demographics

One of the major focus areas of the transformation agenda is to ensure that the composition of the student body progressively reflects the demographic realities of broader society. Institutions are therefore required to develop their own race and gender equity goals and plans.

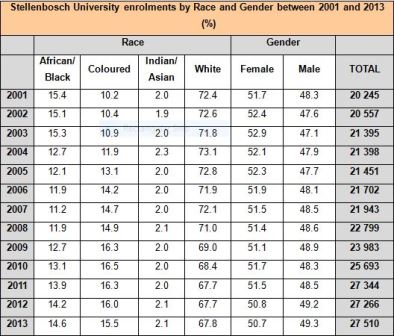

With respect to the student profile of Stellenbosch University, Higher Education Management Information System (HEMIS) data shows that the racial profile within the institution is still mainly white (see table below).

In percentage terms, the number of Africans/Blacks enrolled at the university declined from 15.4% in 2001 to 14.6% in 2013. Surely this is not incidental but engineered. There has also been a decrease in enrolments of White students from 72.4% in 2001 to 67.8%. The two declines, however, cannot be compared as that of White students is on a large composition of the institution.

The student demographic profile clearly does not match the racial demographics in the country. The 2014 mid-year population estimates released by Statistics South Africa show that the Black Africans constitute approximately 80% of the total South African population, followed by Coloureds at 8.8%, Whites at 8.4%, and the Indians/Asians at 2.5%. Given that Stellenbosch University is in the Western Cape, it should be expected that there should be a higher percentage of Coloured students.

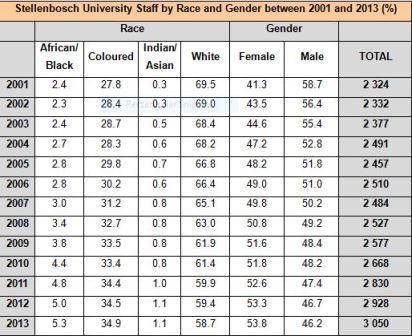

In 1994, academics at South African universities were overwhelmingly white (83%) and male (68%). Over the past two decades the academic workforce has become a little more equitable, though in 2012 the full-time permanent academic staff of 17 451 academics remained largely white (53%) and male (55%).

Although there has been a gradual decrease of white staff members since 2001 at Stellenbosch University, and a proportional increase of Black African and Coloured staff, the staff profile remains largely white. The following table provides information on the demographic profile of SU staff from 2001 to 2013.

The department is concerned that the staff at universities have not transformed sufficiently over the past 20 year. The Department is implementing the Staffing South Africa’s Universities Framework (SSAUF), a programme aimed at revitalising and transforming the academic profession within our institutions.

Ministerial Committee on Transformation and Social Cohesion and Elimination of Discrimination in Public Higher Education

Following the Reitz incident in March 2008 at UFS which received wide media coverage in the country and internationally, the former Minister of Education, Ms Naledi Pandor, appointed a Ministerial Committee on Transformation and Social Cohesion and Elimination of Discrimination in Public Higher Education, headed by Prof Crain Soudien, to “investigate discrimination in public higher education institutions, with a particular focus on racism and to make appropriate recommendations to combat discrimination and to promote social cohesion”.

The Report noted serious disjuncture between policy and real-life experiences of both students and staff, particularly in learning, teaching, curriculum, languages, residence-life and governance. The Committee concluded that the experience of feeling discriminated against, in racial and gender terms in particular, is endemic within our institutions, and that the state of transformation in higher education was painfully slow.

The Report includes some recommendations for the Ministry and the higher education institutions on policies, strategies and interventions needed to fight against discrimination and to promote inclusive institutional cultures for staff and students. The following recommendations were made to the higher education institutions:

-Additional sources of funding to be sought for supporting and mentoring staff members upon their entry into academia.

-The VCs of the institutions to be held directly accountable for the achievement of employment equity targets.

-Council should take direct responsibility for monitoring employment equity by establishing an employment equity sub-committee, chaired by an external member of Council.

-Abolishment of de facto racial segregation and discrimination that result in racially defined room allocations.

-Establishment of processes to ensure that residence committees are demographically representative.

-Review of student orientation programmes to ensure their appropriateness in terms of addressing issues of inclusivity and diversity.

-Banning of all initiation ceremonies and activities, irrespective of whether an activity causes bodily harm or not; and an establishment of a toll-free (and anonymous) complaints line to allow students to register infringements of this policy.

-Development of transformation charters and clear transformation framework, including transformation indicators, accompanied by targets, which should form the basis of the VC’s performance contract.

-Establishment of independent Ombudsman offices, for dealing with all complaints relating to discrimination within the institution.

Recent Incidents on Racism

In 2014 and 2015, four of the historically white universities, namely North West University (NWU), University of Pretoria (UP), University of the Free State (UFS), the University of Cape Town (UCT) and the Stellenbosch University made headlines due to incidents of racism and discrimination.

In February 2014, two white students allegedly deliberately knocked down a black student with a bakkie at the UFS campus. Apparently, when he approached them, he was violently attacked and called a “kaffir”.

In February 2014, a group of NWU students "dressed in uniforms, marching in unison like troopers and, most disturbingly doing the “Nazi-style fascist salute" was reported.

In August 2014, hate speech pamphlets inciting violence against Afrikaans people were circulated at NWU. The pamphlet read: "Attention comrades. Time to take back the NWU. Kill the boer, Kill the racist, Kill Afrikaans. Uhuru anakuja [Freedom is coming]".

In the same month, a picture surfaced on social media of two UP female students with their faces painted brown, wearing domestic worker attire. It is said that the theme of their dress code was about, "what they would not like to be in life".

Following the above-stated UP incident, two white male Stellenbosch University students caused a huge uproar on social media after they posted images of themselves in black-painted faces and dressed up like the Williams' sisters in September 2014. Needless to re-state what was in the public domain after the passing of Professor Russell Botman, of allegations of resistance to transformation by the council which surfaced at the University of Stellenbosch and that his passing away was due to stress incurred due to such resistance and that he was to be subjected to a vote-of-no-confidence.

In September 2014, an alleged racist incident that happened outside a UP residence was reported. White students at the Taaibos residence were racially abused by two black students from the Kollege Tehuis residence.

On 9 March 2015, an independent group of students, workers and staff started a protest movement on 9 March 2015, originally directed against a statue of Cecil John Rhodes at UCT. This brought to surface existing and justified rage of black students against institutionalized racism and patriarchy at the institution, and perhaps at other institutions as well. What started as a protest action against a statue grew into a national debate on transformation at universities and colonial symbols in a democratic South Africa. The reality is that the campaign would not have started if the university was successful in bringing about significant transformation-related change over the past two decades.

Recently, students at the Stellenbosch University released a documentary #Luister which contains interviews of mainly black students describing their encounters relating to incidents of racism and discrimination inside and outside lecture rooms at Stellenbosch University. These are clearly incidents reminiscent of the old apartheid South Africa. Most disturbingly, these incidents of racism and discrimination are seemingly taking place unabated at one of the highly rated institutions of higher learning in our country. The issue is not only about Afrikaans as a language of instruction at the University, but this provides a basis for harbouring racist attitudes among some white students and academics at the university, clearly depicted in the interviews.

These incidents of racism and emerging movements are indicative of the issues of intolerance and hatred among racial groups that the higher education sector still grapples with.

The Meeting of the Minister with the Historically Afrikaans Universities

On 16 April 2015, the Minister met with representatives of Councils and management of the former Afrikaans universities, which included Stellenbosch University. A wide range of issues relating to institutional transformation and acts of racism and discrimination were discussed in a constructive dialogue. Institutions shared their current experiences and exchanged their ideas and plans to advance transformation. The institutional leadership valued the opportunity to learn from one another’s experiences and to engage with the Minister and the Department.

All these universities agreed to deal clearly with issues of social inclusion and cohesion, language and admissions policies. Although these institutions indicated that they are working on these matters, the student experiences show otherwise, thus some of the institutions are still regarded as bastions of the old South Africa.

Universities have designed programmes and set up units to address transformation, but there is a need to move beyond policy formulation and to create an observable shift in institutional cultures. In other words, meaningful change has to be seen in the academic, social, economic, demographic and cultural domains of institutional life.

The University appointed Professor Wim De Villiers as the Rector and Vice-Chancellor, following the sudden death of Professor Russel Botman. He was appointed by the University Council on 1 December 2014, and was inaugurated on 29 April 2015. The Minister is advised to acknowledge the efforts and initiatives that the Professor Wim De Villiers, is making to rid the institution of the culture of discrimination and bring forth transformation and social cohesion. These are the establishment of a transformation office and transformation committee.

While the Department welcomes and supports these initiatives, they require speedy actions which have to yield quick and sustainable results. The university council and management must work on the culture and attitudes of the whole of its community and constituency, as everyone must be treated equally and have a fulfilling experience at the university. The university must be welcoming to all who would want to study at an institution of higher learning.

Higher Education Summit

The Minister will be hosting a Higher Education Summit on 15 - 17 October 2015. The main theme of the summit is the transformation of higher education, and he urges higher education stakeholders to participate in a spirit of constructive debate, openness and very honest introspection of the sector. The aim of the summit will be to develop clear concrete strategies for deepening transformation and tackling difficult questions about the roles and nature of universities in South Africa today, with clear and implementable outcomes.

The Transformation Oversight Committee

The Department is in the process of establishing a Unit to support the Transformation Oversight Committee so it can fulfil its mandate, which is to:

-Study and evaluate the transformation frameworks/charters and annual reports of all universities, including their transformation indicators and set targets and use this as a basis for the development of a transformation charter and benchmarks for the entire university sector;

-Determine the effectiveness and efficiency of institutional transformation frameworks/charters, policies and strategies;

-Produce an annual report on policies and practices impacting on transformation within universities, including both achievements and challenges;

-Suggest a reporting mechanism by institutions on the set institutional and national transformation targets and benchmarks;

-Identify best practices and challenges in the area of transformation policies and practices;

-Bring to the attention of the Minister any major problem areas or incidences affecting universities’ transformation;

-Advise the Minister on policy and strategies for the promotion of transformation and any other matters it may deem necessary, important and relevant for development and transformation of the sector.

The existence and the work of the Oversight Committee is clearly an important one in accelerating transformation and eradicating acts of racism and discrimination in the higher education institutions.

Thank you.

Statement issued by Blade Nzimande, minister of higher education, 3 September 2015