The crisis in South Africa's trade union movement

Over the past two years, South Africa lost nearly double the number of work-days due to strikes and work stoppages (about 16 million in each year) than under the peak of rolling mass action under apartheid (9 million in 1988). The World Economic Forum (WEF), the world's most influential body of investors and employers, ranks South Africa as the 8th worst country in the world (132nd out of 139 countries) in terms of labour/employer conflict.

Industrial conflict is not the only or even the most important issue: the WEF cites restrictive labour laws and a poor national work ethic among the most problematic factors for doing business in South Africa. But growing trade union-related protests have a special significance.

On a practical level, they disrupt business activities and cause businesses to renege on supply commitments to their customers, which are mostly other (and increasingly foreign) businesses. On a political level, they create the impression that workers are highly disgruntled with their pay and working conditions and that worker rights are widely flouted.

Where trade unions have been successful is in raising wages. Between 1995 and 2011, after-inflation remuneration in the non-agricultural formal sector has increased from R9,378 per month to R12,564 per month. In the 15 years since the Labour Relations Act (LRA) was introduced, after-inflation wages increased by 28.8%, which is nearly treble the increase in the preceding 25 years.

Per unit of productivity, real wages have increased at an astonishing average annual rate of 7.6% - or 200% in total - since the LRA was introduced. But even higher wages have been a mixed success, since they have occurred at a cost of lost jobs and, by implication, falling union membership. In 2011, it took 36% fewer workers to produce a given level of output than it did in 1960, mainly due to the economy's sharply rising capital intensity.

Where trade unions have failed is in the area of labour relations. Certainly union claims of poor working conditions are not borne out by other statistics. In 2010/2011, the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) received 156,000 referrals from disgruntled employees through its network of about 200 venues across the country. About 62% of referrals were settled in favour of employees, against employers.

The CCMA only deals with serious cases where employees have been unable to resolve their complaints directly with their employers: 81% of referrals relate to a dispute concerning an employee's dismissal. The Labour Court and Labour Appeal Court, where the most difficult cases are dealt with, made 2,042 decisions in the last year, and roughly one-half of judgments were in favour of employees.

The long-term trend of CCMA and Labour Court records shows that workplace conflict has been largely unchanged over the past decade. If these figures are a guide, then on average 1.2% of the total South African workforce formally raises disputes in a given year, and 0.7% have sufficiently convincing arguments leading to a settlement in their favour. Unfortunately there are no official statistics on the extent of employee complaints within companies.

Also, it is likely that the CCMA and Labour Court deal primarily with formally employed people who possess written employment contracts, and a growing number of South African employees do not have these characteristics. But it seems clear from these figures that the dramatic surge in strikes and work stoppages in recent years overstates the general degree of conflict in South African workplaces.

Trade unions have many goals, which naturally include improved pay, benefits and working conditions for workers. But there are other goals: growth of trade union membership, reducing the spread and influence of rival unions, promoting compulsory union membership ("closed shop" agreements) and mandatory payment of union dues by non-union members ("agency shop" agreements).

The most disturbing union goal involves reducing competition from new entrants into the labour market, particularly unemployed youth, who put downward pressure on wages and benefits levels for established workers.

It is in this context that trade unions have opposed such varied phenomena as the Minister of Finance's youth employment subsidy (which was expected to be announced in the 2012 budget but which was abandoned due to trade union opposition) and "labour brokers" (temporary employment agencies) whose candidates - 82% African, 75% youth, and 50% never previously employed - represent a distinct threat to established worker interests and, as a consequence, trade union membership.

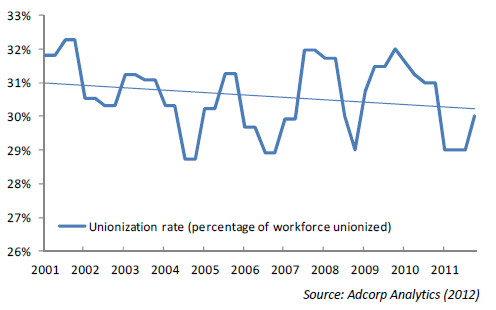

Trade unions, viewed as economic entities, have suffered three major setbacks in recent years. Firstly, trade union membership has fallen since official records began in 2006, from 3.5 million to 3.3 million members, a loss of 129,424 members representing lost membership dues of R95,773,760 per annum. Trade union membership as a proportion of the total workforce is slowly but steadily declining (see figure).

And the overall unionization rate (29% of the total workforce in 2011) conceals a dramatic change in the composition of union members: unionization in the private sector has fallen to an all-time low (26% of the private sector workforce), whereas unionization in the public sector has risen to an all-time high (75% of the public sector workforce). It is possible that growing trade union support for greater government participation in the South African economy has been driven, at least to some extent, because the public sector has been the overwhelming growth vector for trade union membership in recent years.

Unionization rate, 2001-2011

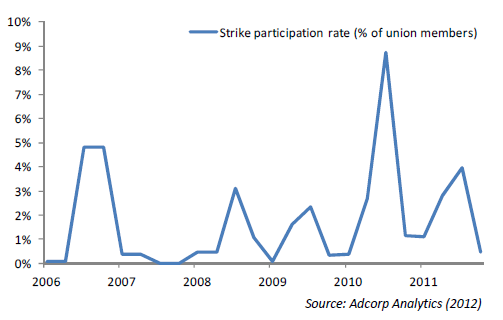

Secondly, union members' participation in strikes has been generally very low (on average since 2006, just 1.4% of trade union members turned out on strike) and highly variable (ranging from 0% to 8.8%, depending on the goals, duration and time of year of individual strikes). This explains why strikes and union-initiated protest actions have grown greatly in range and scope. For example, in light of uncertainty as to how many union members would turn out in support of the 7 March 2012 nationwide protest action, trade unions have added multiple objects to their protests (opposition to labour broking, resistance to Gauteng's e-tolling system, and hostility toward Eskom's tariff hikes).

Strike participation rate, 2006-2011

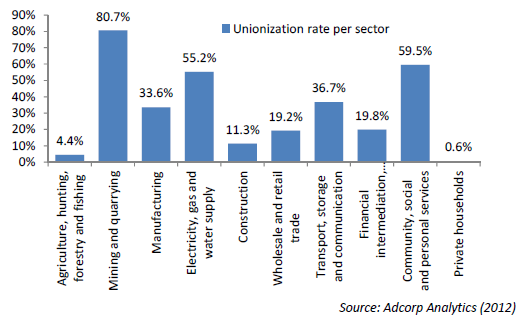

Thirdly, trade unions suffer from variable membership by sector. In some sectors, such as mining, as many as 80.7% of employees belong to a union. In other sectors, such as agriculture, just 4.4% of employees belong to a union. This points to difficulties that unions have in organizing in fragmented, heavily segmented sectors, including construction, retail, and finance. In other sectors, where employees tend to be concentrated on large sites such as mining, manufacturing, electricity and, especially, government, unions' ability to organize workers is much greater.

Unionization rate per sector, 2011

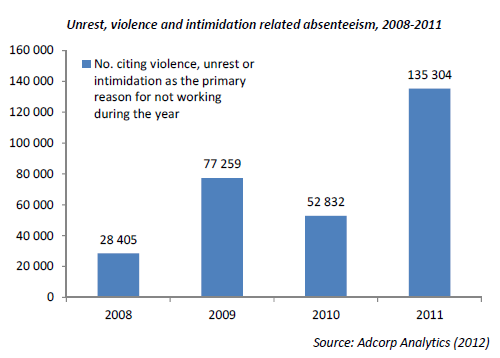

Low, variable turnout rates appear to be connected to growing violence and intimidation during strikes. Official figures are not reliable, but absenteeism due to unrest, violence and intimidation, while low overall, has increased significantly. In the first 12 months of 2011 alone, 135,304 workers cited unrest and violence as the primary reason for being absent from work, representing 19.6% of all non-statutory absenteeism.

Unrest, violence and intimidation related absenteeism, 2008-2011

If the number of union-related strikes and work stoppages is symptomatic of genuine employer/employee conflict in South African workplaces, official figures from the CCMA and Labour Court do not bear this out. Rather, it appears that rising industrial unrest has emerged in response to gradually declining union membership and low worker participation in strikes. Several apparently unrelated phenomena - the call for greater public sector employment, the appeal to ban labour brokers, opposition to the youth employment subsidy, growing violence and intimidation during strikes, and greater union participation in secondary interests such as toll fees, electricity tariffs and corruption in government procurement - appear to have a similar origin.

This is an extract from the Adcorp Employment Index for March 2012, released on April 9 2012

Click here to sign up to receive our free daily headline email newsletter