Reprehensible Tweets: Why Prohibition is the Wrong Response

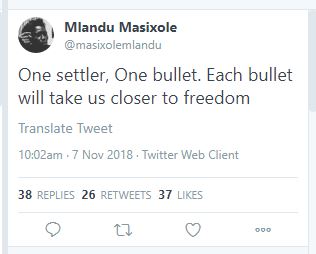

On the morning of Tuesday 6 November 2018, University of Cape Town (UCT) student Masixole Mlandu tweeted the first few pages of his Political Studies Honours research project. The acknowledgements page ended with the words “ONE SETTLER, ONE BULLET!!” (Capitals in the original.) The following day, Wednesday 7 November, after significant indignation had been expressed in response, he expanded his point by tweeting as follows: “One Settler, One Bullet. Each bullet will take us closer to freedom.”

Exactly what Mr Mlandu meant by his Tweets is not clear. He may have meant them as a call for a genocide against millions of his fellow South Africans. Or he may have meant them only to express the view that such a genocide would be desirable or would be deserved by its victims. Either way, the tweeted words are morally repugnant. Reasonable people, whether or not they identify themselves as “settlers”, will and should be outraged by them.

But should Tweets like Mr Mlandu’s be prohibited?

It is probable that his Tweets are prohibited by section 10 of the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act. Under the heading “Prohibition of Hate Speech”, the section states that “no person may publish, propagate, advocate or communicate words based on [race, ethnic or social origin, colour, or culture] against any person, that could reasonably be construed to demonstrate a clear intention to – (a) be hurtful; (b) be harmful or incite harm; (c) promote or propagate hatred.”

Relying on this section, the Equality Court found that a Facebook post by Penny Sparrow, which referred to “black” people as “monkeys”, constituted hate speech and justified an award of damages against her of R150 000, to be paid to the Oliver and Adelaide Tambo Foundation. If, as is generally believed, the Equality Court’s application of section 10 in the Sparrow matter cannot be faulted, it is hard to see how Mr Mlandu’s Tweets would not likewise constitute hate speech (as section 10 defines it) and would not also justify a substantial award of damages payable to a foundation promoting “non-racialism, tolerance, [and] reconciliation”.

It is possible that Tweets like Mr Mlandu’s also are prohibited by UCT. UCT’s “rules on conduct for students” include rule RCS7.6, which forbids students from acting or threatening to act “in a manner which interferes with the work or study of any member of staff or student … in relation to the person’s race …”, and rule RCS7.7, which forbids students from abusing “any member of the University community in any manner which contributes to the creation of an intimidating, hostile or demeaning environment … in relation to the person’s race …”. It might be said, not wholly implausibly, that Mr Mlandu’s Tweets constitute a threat of the kind prohibited by the first of these rules, as well as abusive behaviour of the kind prohibited by the second.

Even if Tweets like Mr Mlandu’s are prohibited by South African statute and by UCT’s rules, they ought not to be – both constitutionally and morally. First, there is reason to believe that such prohibition is unconstitutional. Section 16(1) of the South African Constitution confers upon everyone a right to freedom of expression. However, according to section 16(2)(c), this right does not extend to “advocacy of hatred that is based on race [or] ethnicity … and that constitutes incitement to cause harm” (our emphasis). Mr Mlandu’s Tweets almost certainly advocate hatred based on race or ethnicity. They almost certainly endorse the doing of harm by some to others. The intention behind them may have been to encourage such harm-doing. And it is possible that they might make such harm-doing more likely.

However, for Mr Mlandu’s Tweets to fall outside the ambit of the constitutional right to freedom of expression, because they fall within the exception created by section 16(2)(c), that is not enough. It is necessary, in addition, that the Tweets constituted “incitement to cause harm”. As a number of legal philosophers have noted, the requirement of “incitement” sets a high threshold. For that threshold to be met, harm must not only be a probable consequence, it must be “imminent” or “in the very near future”. There must be “a real threat to public safety”, as there would be when – to borrow Joel Feinberg’s metaphor – we have an “incendiary context” in which the audience is “tinder” and words advocating racial or ethnic hatred are intended as a “spark”.

Mr Mlandu’s Tweets have constitutional protection, therefore, notwithstanding the likely intention behind them, which is reprehensible, and notwithstanding that they may contribute to appalling long term effects. The reason is their context. South Africa is not (yet?!) on the brink of genocide, and its citizens are not so resentful, nor so filled with hatred, nor so inclined to violence, that Tweets like those of Mr Mlandu will tip them, almost unthinkingly, into the blood-letting that he possibly dreams of and hopes for.

If we are correct that Mr Mlandu’s Tweets are constitutionally protected, it remains an open question whether they should be. Put another way, why – morally speaking – should the Constitution protect hateful Tweets? Words can have harmful consequences. Why should only imminent harms count as incitement? If an incendiary climate can be created by a steady accretion of hateful words, why should we not ban such words before there is tinder susceptible to a spark?

The answer is multifaceted. First, freedom of expression is a very important value. Second, it is often difficult, as we noted above, to differentiate the expression of a hateful opinion – for example, that all “whites” should be killed – from the intent to incite harmful action.

Third, and precisely because of this, freedom of expression can easily be eroded if one fails to maintain a high threshold for what counts as incitement. If merely contributing towards the creation of an incendiary climate counts as incitement, then the expression of many opinions could be counted as “incitement” and thus banned.

Fourth, this is unlikely to be done consistently, with those most vulnerable to violence from the creation of an incendiary environment also least likely to be able to curb the speech that would create such an environment.

Fifth, allowing hateful speech, morally repugnant though such speech is, has beneficial side-effects. About a year ago, a Berkeley University student newspaper published a cartoon of Harvard Law School Emeritus Professor Alan Dershowitz, which he subsequently criticised as anti-Semitic. Professor Dershowitz nonetheless was “adamantly opposed” to “censoring the anti-Semitic cartoon”. As Professor Dershowitz explained, “I want the world to see it and hold accountable those responsible for it”.

The same applies to Mr Mlandu’s Tweets. Given his leading role in the UCT disruptions of the past few years, it is good that as many people as possible get to see the moral repugnance of his views. That he endorses a genocide of millions, or thinks that it would be desirable or deserved, is something that everyone with an interest in UCT should know. Among other things, it raises serious doubts about the process and findings of UCT’s Institutional Reconciliation and Transformation Commission (IRTC).

Mr Mlandu was one of seven students granted amnesty by UCT on the basis of the IRTC’s recommendations. He must therefore have provided the IRTC with evidence of his contrition, or at least of an acknowledgement that he had done wrong. Mr Mlandu’s Tweets suggest that this evidence was provided without sincerity. And it suggests that the IRTC was naïve to accept it at face value.

Mr Mlandu’s Tweets, and the views they show him to hold, also have implications for the “diversion programme”, managed by the National Institute for Crime Prevention and the Reintegration of Offenders (Nicro), that he reportedly was placed on earlier this year. This was after he was charged with malicious damage to property, public violence, contempt of court, and contravention of the Intimidation Act, all in relation to an incident at UCT.

The aim of the diversion programme is rehabilitation, and those on the programme must provide proof that they have seen the error of their ways. Mr Mlandu’s Tweets suggest that he has not. It is good that we (and Nicro) know this. It would similarly be good to know how many of Mr Mlandu’s comrades and their defenders hold genocidal views. If speech of this kind is prohibited we are less likely to find out who has such views.

This leads to a final reason for why the threshold for what counts as incitement should be kept high. There is a long causal chain between Tweets such as Mr Mlandu’s and the violence he would like to see. There are much better ways than restricting freedom of expression to prevent the former from resulting in the latter. These include holding people such as Mr Mlandu to account for their actions – rather than mere words. This is especially true when their actions are not only prohibited but also justifiably so.

Yet holding people such as Mr Mlandu to account for their actions is exactly what UCT has consistently not done. Worse still, following Mr Mlandu’s initial Tweet about his Honours project, UCT’s Vice-Chancellor, Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng, replied on Twitter as follows: “Congratulations dear son on completing this paper! I would like to study it at some stage. In the meantime, let me be kliye: i am proud of you! Way more than you can imagine! Welldone!”

This was rightly met with widespread indignation by those who are opposed to genocide. Professor Phakeng responded by clarifying that “Of course I can never be proud of promises of bullets, what I am proud of is the fact that you did the paper and completed it”. UCT also issued a statement noting that both Professor Phakeng and the institution distanced themselves from Mr Mlandu’s “language”.

But saying that one distances oneself is different from actually distancing oneself. (Think of Donald Trump’s tepid condemnation of “white” supremacists.) We doubt that the Vice-Chancellor would publicly express pride in a student who, in the acknowledgements of his Honours project, called for the return of Apartheid, let alone a genocide of South Africa’s indigenous peoples. And if she were to do so, subsequently distancing herself from such “language” would not be regarded as sufficient.

That she and others are fixated on a hateful slogan rather than on the underlying pathology of the institution is but another symptom of the deeply toxic environment that currently prevails at UCT. It is that environment that should never have been allowed to develop and which should now be corrected. There is no evidence that it is being fixed. Indeed, the problem seems to be deepening. If that trajectory continues, there will be awful consequences whether or not the likes of Mr Mlandu advocate violence.

What is good for the goose is good for the gander. During the past few years, freedom of speech has been significantly eroded at UCT. The most notable infringements of this freedom were the de-platforming of Flemming Rose and the destruction, removal, and covering up of artworks on UCT campuses. If, as we have argued, the right to freedom of speech is sufficiently robust to protect Mr Mlandu’s Tweets, notwithstanding their moral repugnance, it is, a fortiori, robust enough to have protected Flemming Rose against being silenced and to protect the many notable South African artists whose artworks were removed or covered up from being rendered invisible. This has a further implication.

It shows that, even though (for the reasons we have given) UCT has done the right thing by not taking disciplinary action against Mr Mlandu for his reprehensible Tweets, it has not done so because of a highly principled commitment to freedom of expression.