When Peter Mackay died in 2013 at his well-kempt, humble cottage home in Marondera (the former Marandellas) he was 86. He was, wrote the historian Terence Ranger, living by himself in deliberate obscurity. Millions of words have been written about the history of Rhodesia. There have been dozens of books about the long and costly war (1966-1979) that ended 90-years of all-white rule in Southern Rhodesia in 1980.

But Peter Mackay’s name is mentioned in only four of them: two are by critics, with author Richard Hughes Capricorn – David Stirling’s Second African Campaign (The Radcliffe Press, 2003) presenting Mackay as a slightly maverick figure in the European-run “liberal” attempt to end racism in the British colony and Ken Flower’s memoir of Rhodesian intelligence Serving Secretly, Rhodesia into Zimbabwe 1964-1981 (John Murray, 1987) where Mackay appears, absurdly, as a KGB agent and a man condemned by most Rhodesian whites as a supporter of Africans (the racist slang reading “Kaffir-lover”).

The other two, throw a different light on the man and are in Judith Todd’s Through the Darkness: A life in Zimbabwe (Zebra Press, 2007) and in Ranger’s Are We Not Also Men – The Samkange Family and African Politics in Zimbabwe 1920 -1964 (James Currey, London 1995). Otherwise, notes Ranger in the foreword to Mackay’s own work We Have Tomorrow – Stirrings in Africa, 1959-1967 (Michael Russell, London 2008) “he has gone unnoticed in the whole vast literature of African nationalism in Central Africa and the liberation war in Zimbabwe.”

Very few people knew that during years of sometimes feverish activity on behalf of the African nationalists fighting Rhodesia’s relatively well-equipped army, Peter Mackay was keeping a diary of events which young African historians will find so useful.

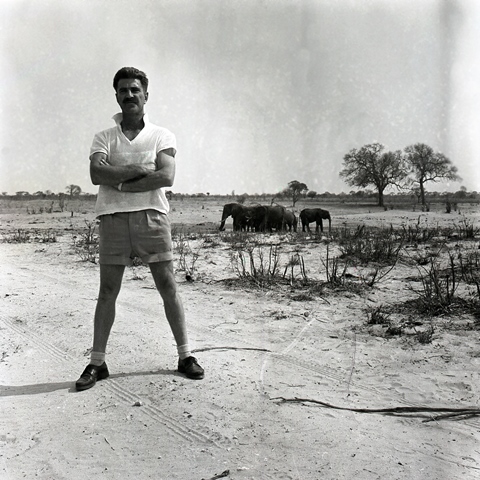

The entire Peter Mackay Archive has now been shipped to Stirling University in Scotland. Students at that great university have taken Mackay to their collective heart, decorated walls at the campus with pages from his book, illustrated the heroic journeys he made between Rhodesia-Botswana – the Caprivi Strip –Zambia-up into Tanzania and then beyond (sometimes to the Soviet Union countries, sometimes to China/ North Korea) a political/military/liberation highway known to Mackay’s growing number of supporters and admirers as Freedom Road.

“Mackay played a crucial role in the liberation of Zimbabwe but his stories have not yet been fully told,” said Ireland-born Karl Magee, the university’s chief archivist. “We want to make Mackay’s personal and political papers, and photography accessible to scholars and students in Africa and open up one of the most important collections of its kind, to the rest of the world.”

His ties to Stirling were strong. His upper-middle class family with its distinctly imperial connections lived at nearby Doune. Peter’s father served as a major in the Gurkha Rifles and one of his uncles also joined that famous unit and became a colonel. The young Mackay went on to become head boy at Stowe (senior boys were called “men” at English private schools) and then the youngest captain in the Brigade of Guards. His family and his peer group at Sandhurst saw him as a general in the making.

Instead of pursuing a military career, he left the army and became a tobacco farmer in Southern Rhodesia, later editor of that country’s main farming magazine and then as a man determined to help change the face of Africa by lending his military expertise to black nationalists during the first and arguably most complicated period of their coming together as opponents against first, the Central African Federation that linked the two Rhodesia with Nyasaland between 1953-1964 and then Ian Smith’s Government (1964-1978).

The turning point in Mackay’s extraordinary life happened when he met Colonel David Stirling, founder of the legendary SAS. He dropped farming and lent himself to the progress of the multicultural, liberal Capricorn Society, organising its most successful venture – the Salima Convention on the shores of Lake Malawi in June 1956.

Mackay was jailed for refusing to serve in the Rhodesian Army. He re-based in Kenneth Kaunda’s Zambia, worked with refugees in Lusaka and became a strong supporter of FROLIZI, the tiny liberation movement led by James Chikerema and George Nyandoro after their break with both ZAPU and ZANU in 1971.

It is not known how many young blacks Mackay shepherded out of Southern Rhodesia into guerrilla training camps in other parts of Central, Eastern and Northern Africa (and beyond). Some say hundreds – others insist it was much more – maybe thousands.

In one of his rare discussions with a journalist he said: “My politics were the politics of race – majority rule and not the politics of party. I never did like politics. Nearly every political prediction I made was wrong.”

After Independence in 1980, Mackay watched the men he’d help to power climb the greasy pole and become as greedy and corrupt as the worst of the men they’d removed from power.

Peter set off to Omay in the Zambezi Valley, one of the most malaria-infested parts of Zimbabwe where he set up a health clinic and school and an agricultural settlement for the 15, 000 Batonka tribespeople who occupied that long neglected, impoverished, area.

“In many ways,” said the writer and historian Lawrence Vambe (An Ill-fated People – Zimbabwe Before and After Rhodes – published by William Heinemann, London 1972)”Peter was a kind of saint. But a non-religious saint if there can be such a person.”

Six years before his death, thieves broke into his cottage. Peter was in the bath. The cottage was ransacked. Armed robbers stole what money Peter had in a drawer. A fierce fight followed. Peter was almost beaten to death.

The years the Peter Mackay Archive cover are still comparatively recent. But as the author Michaela Wrong (In the Footsteps of Mr Kurtz – Harper Collins, 2000) said in a review of Peter Mackay's wonderfully frank and beautifully written book: “The hopes of that era were so bright, the belief that an independent Africa would prove a better place than its colonial predecessor so unquenchable, this story seems to hail from a different century, or perhaps a parallel universe.”

Trevor Grundy is a British journalist who worked in Central, Eastern and Southern Africa from 1966-1999.

Peter Mackay pictured at a point along Freedom Road. Courtesy of the Peter Mackay Archive, Stirling University, Scotland