The NIGHTMARE FROM WHICH WE ARE STILL TRYING TO AWAKE (II)

Note to readers: this series was sparked in part by revelations and claims in three recent books about South Africa – Jonny Steinberg’s “Winnie & Nelson,” Justice Malala’s “The Plot to Save South Africa,” and Eve Fairbanks’ “The Inheritors”. Quotes attributed to these authors are derived from the works aforementioned.

This article is the second in the series. The first article can be read here.

Introduction

The first article in this series on the curse of violent crime in South Africa traced the situation in South Africa through the last decade of PW Botha’s presidency and apartheid proper.

Under segregation and apartheid white South Africans had been largely shielded from the violent criminal predation that afflicted many black urban communities. Through the national insurrection of the mid-1980s, and despite an explicit effort by the African National Congress to take the struggle into the ‘white areas’ from late 1985 onwards, this pattern had held up until 1988.

The shock caused by the force and fury of this insurrection, South Africa’s growing isolation, and the knowledge that the relative position of the white minority would only deteriorate further over time – combined with the retreat of the Communist threat - led significant factions of the white ruling establishment to start exploring the possibility of a negotiated settlement with the ANC.

This article picks up the narrative in 1989, the year that the political transition from apartheid and white rule was set in motion.

Liquidating the firm

In 1989 FW de Klerk replaced PW Botha as leader of the National Party and then President of South Africa. After winning the last whites-only elections in September 1989, De Klerk charted a course towards political transition, or the “liquidation of the firm” as NP insiders sometimes put it. The Rivonia trialists (other than Mandela himself) were released October, and a moratorium placed upon capital punishment. From the ANC side the second half of the year saw a marked decrease in MK guerrilla activity.

It was in 1989 too that General Bantu Holomisa formally unbanned the liberation movements in the Transkei homeland and released MK operatives held in Transkei prisons, along with those of the Azanian People’s Liberation Army (Apla), armed wing of the Pan Africanist Congress.

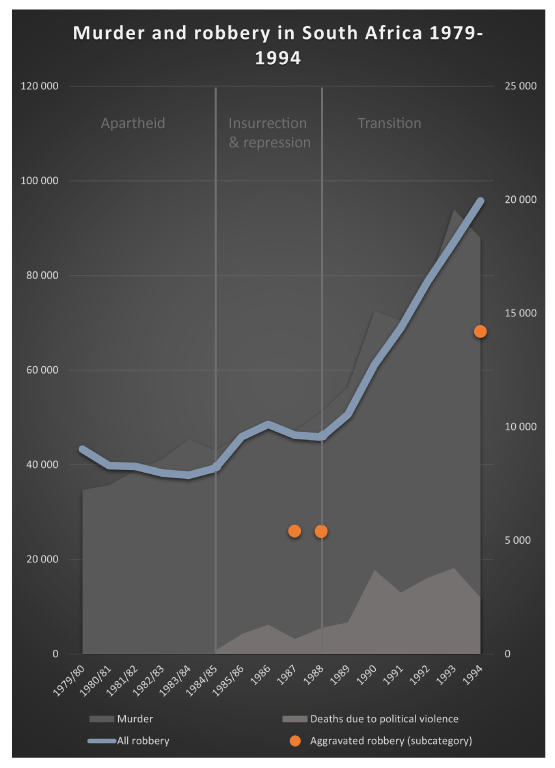

The escalating conflict between the ANC and Inkatha in Natal continued to push up political fatalities which increased in that province from 912 in 1988 to 1279 in 1989 – 92% of the 1 403 political fatalities counted that year by the SAIRR. There was a slight deterioration in the overall crime situation, with robberies up 10,4% to 50 636 and murders up 9,5% to 11 750, an increase again driven by the rise in political violence. But only 305 of these murder victims nationally were white, signalling that white areas were still largely untouched by the violence that was wracking other parts of the country.

In February 1990 De Klerk followed Holomisa’s example, announcing the release of Nelson Mandela and all remaining political prisoners and the unbanning of the ANC, SACP and PAC. In the same speech, he declared his intention to abolish all remaining security and apartheid laws and lift the state of emergency.

De Klerk’s move failed to bring down the temperature of the conflict in Natal. There were 695 political fatalities counted by the SAIRR in Natal in the first three months of 1990, more than double the number of the equivalent period of the year before. Elements within the security services continued to run guns to Inkatha in early 1990, while the ANC policy of providing young comrades with weapons to take out Inkatha members seems to have carried on unimpeded, as did Operation Vula, the ANC’s secret attempt to reestablish key leaders and stockpile arms inside South Africa.

The goal of Operation Vula was for MK to quietly reestablish itself in the country and take command of, recruit for, train, arm, and then direct the combat and self-defence units of the fighting youth. In this way MK would summon into existence, and form the core of, a “revolutionary army of the people”. A high priority was also the formation of combat units to carry out operations in cities and on white-owned farms. The activity of such units would be guided by the needs of the political struggle, but the groundwork would be steadily laid for a return to full-scale insurrection, should the right moment present itself.

In early July the Security Police, acting on a tip off, raided two Vula safe houses and uncovered the ANC’s secret plans. This led to seizure of a huge quantity of weaponry and the arrest of several ANC and SACP figures involved in the operation. Ronnie Kasrils had to go back underground, while MK Chief of Staff Chris Hani sought refuge in the Transkei under Holomisa’s protection.

Embarrassed by these developments and eager to avoid a wholesale clampdown, the ANC agreed, in terms of the Pretoria Minute signed on 6th August 1990, to “suspend all armed actions with immediate effect.” As of that date, therefore, all main armed actors in the conflict – the ANC, the NP government and Inkatha – were formally committed to peaceful resolutions. As we shall see, however, this did not mean the end of political violence; only that violence would henceforth proceed along covert and “deniable” lines.

The apartheid state’s dirty war

In his book Days of the Generals the journalist Hilton Hamman claims that covert units in De Klerk’s police and military were instructed by their political superiors to “disrupt” the returning ANC, an order he suggests was interpreted with “the broadest possible latitude.” These units, it seems, continued to conduct covert operations, with some elements in the SADF’s spesmagte (special forces) later conducting pseudo-operations, while others continued their practice of simply assassinating the enemy. There would also be extensive gun running to proxies within the black population who were willing to fight the ANC. Most such activities remain shrouded in secrecy, but Eugene de Kock later confirmed that he armed Inkatha warriors during his tenure as commander of the Vlakplaas counter-insurgency unit. This would come to be characterised as “third force” activity.

Within days of the exposure of Operation Vula in July 1990, political violence between the ANC and Inkatha spread from Natal to areas around Johannesburg. The proximate cause, Jonny Steinberg writes in Winnie & Nelson, was the effort to launch Inkatha as a national rival to the ANC. The ensuing war never engulfed the whole city, with the violence in Alexandra, Kagiso, Jeppe, and Soweto, remaining sporadic and fairly low-key. “But in two townships to the east of the city, Thokoza and Katlehong, the war was bitter and endless and shockingly bloody.”

In The Inheritors Eve Fairbanks describes the nightmarish political violence around Johannesburg through a focus on Katlehong. It was here that 32 Battalion to which Christo, another of the subjects of her book, was attached and was first deployed, with uniformed units of the military now expected to step in and restore order. Fairbanks also describes the fury that the journalist Wally Mbhele felt at FW de Klerk personally, as he covered the violence for the Weekly Mail, over the “hidden hand” that he believed lay behind this horrific mayhem.

A characteristic of De Klerk’s leadership through the transition, however, was his reluctance to decisively control and exercise state power. Instead, he kept the military and the police, and later even the National Intelligence Service (NIS), at a safe political distance. Responsibility for keeping a check on state malfeasance was meanwhile outsourced to various commissions and counter-intelligence investigations.

The Vula plan continues

Steinberg writes that as the violence exploded around Johannesburg in late 1990, Nelson Mandela “grew very angry with De Klerk” whom, he believed, “either was allowing his security forces to inflame the conflict or was too afraid to stop them”. In response, Mandela secretly authorized the procurement “of large stocks of AK-47 assault rifles, Makarov pistols and grenades” to be distributed to the members of the ANC’s “Self-Defence Units” (SDUs) in the areas in and around Johannesburg.

Although these units had initially emerged in a spontaneous manner - or so the story went - MK operatives would now be formally deployed to both train and command them. Among those at the heart of the operation, Steinberg writes, was Ronnie Kasrils, a senior figure in MK. He was a fugitive when the violence erupted, thanks to his Vula involvement, with “the police on his tail” even as he began his work with SDUs. “Years later,” Steinberg continues, “(Kasrils) recalled a secret meeting with Nelson and the ANC’s treasurer, Thomas Nkobi, who quite literally handed Kasrils bags of cash to buy weapons, while Nelson grimly looked on.” Winnie Mandela was also deeply involved in the supply of weapons to SDUs engaged in township battles against Inkatha, something which did not necessarily please Nelson.

The suspicion that state elements were fomenting the violence around Johannesburg was widely shared by the press, foreign diplomats, and the NIS itself. This made it easier for the ANC to continue critical aspects of the Vula plan without being criticized for its failure to truly abandon the armed struggle.

As explained in Part I of this series, MK had tried and failed in 1986 to “plunge itself into the country, train and arm our people” with the goal, at the time, of taking its People’s War into white areas. This time around, MK members could freely enter and move around the country, link up with the young comrades, organise them into combat units (now rebranded as SDUs), and supply them with weapons training and arms. They would also be taught how to surveille and then attack targets.

While ANC talked peace, love and understanding to Western journalists and diplomats, its township recruits were being taught struggle songs that celebrated violence against black “sell-outs” and the “Boers”. These included ‘Shaya maBunu’ (smash the Boers), ‘Dubul' ibhunu’ (shoot the Boers), and MK’s anthem ‘Hamba kahle, Mkhonto’, which contains the line, ‘We, the people of MK, are determined to kill these Boers.’

These factors –sinister Third Force operations, inflamed Zulu nationalism and the ANC’s implementation of its plan to reconstitute, train, and arm its combat units - resulted in a huge increase in politically-related fatalities in Transvaal province, which jumped from 54 in 1989 to 1 547 in 1990, according to the SAIRR. Overall political fatalities increased year-on-year by 163% to 3 699. The number of murders recorded by the SAP increased by 3 359 (28,6%) to 15 109 in 1990, largely driven by the rise in “black-on-black” violence.

In September 1991 the ANC secured further operational space for the SDUs when the National Peace Accord gave them semi-official status, stating that all individuals had the legal right to “establish voluntary associations or self-protection units in any neighbourhood to prevent crime and to prevent any invasion of the lawful rights of such communities. This shall include the right to bear licensed arms and to use them in legitimate and lawful self-defence.”

Elements of the Vula operation that evaded detection by the Security Police in July 1990 would carry on running firearms and other weapons to the SDUs until the end of 1993.

Hani and Holomisa

In the early 1990s, as Mandela pursued the objective of a peaceful transfer of power, Chris Hani would continue “conscientizing” the masses. In her book Eve Fairbanks uses the recollections of her subject Dipuo to contrast Mandela’s “forgiving attitude” with Hani’s militant radicalism. Dipuo, she writes, remembered Hani’s attitude as being “’these people [whites] must go. They must go back to Europe!’ She let out a warm, nostalgic laugh. But in the early ’90s, ‘Nobody could say Mandela was wrong,’ she said.”

In reality Hani’s approach and Mandela’s were complementary rather than contradictory. In its seminal 1962 programme The Road to South African Freedom the SACP had theorised that white rule would be ended either through “insurrection” or “peaceful transition”. The illusion that the white minority could continue governing in perpetuity would ultimately crumble, it stated, “before the reality of an armed and determined people”. Once that happened, “the crisis in the country, and the contradictions in the ranks of the ruling class, will deepen. The possibility would be opened of a peaceful and negotiated transfer of power to the representatives of the oppressed majority of the people.”

When the imprisoned Mandela took the personal initiative to pursue negotiations, he was acting in total accordance with this foundational party doctrine, which clearly envisions talks taking place alongside moves to arm “the people” and deploy firebrands like Hani to steel their resolve. The more armed and determined “the people”, the weaker the negotiating position of the white minority, and the more likely its capitulation to ANC demands.

The writings of both Steinberg and Malala reveal that Mandela and Hani were personally and politically closer than previously known. It was Hani, Steinberg suggests, whom Mandela relied upon to run the operation to spirit key state witnesses out of the country, thereby effectively scuppering the prosecution case against Winnie for her involvement in the kidnapping, assault, and murder of Stompie Seipei.

Malala writes that Hani was far more like Mandela than people assumed, given the contrasting myths that enveloped their respective personas. “The most striking similarity was that both were masters at studying their enemies before seducing them.” Hani was quite capable of providing reassurances to the white minority when the situation required it. In a Newsweek interview in March 1993, cited by Malala, Hani even spoke in favour of some temporary power sharing arrangement with the white minority, adding that “We want to convince whites that democracy is better than apartheid, that… they will continue having a better life and a more normal life. They won’t fear the Blacks they’ve feared for years.”

Mandela, for his part, had great affection for Hani. He saw his younger self in the MK Chief-of-Staff. They would meet at least once a week and, according to Malala, Mandela “pointedly asked his aides to include Hani on his trips and meetings whenever the younger man was available. He recognised Hani as the great hero of the country’s angry and impatient youth. But his desire to keep Hani close went beyond practical considerations: he loved him like a son.”

The third person in this triangle was General Bantu Holomisa, the military leader of the Transkei. Malala describes Hani as a close friend and confidant of Holomisa, with the two men meeting regularly, and working closely together. Holomisa had also become a favourite of Mandela’s from their first meeting in 1990.

As his authorised biographer relates, in 1990 Holomisa opened up the Transkei as “a place of refuge and a transit territory for MK and APLA. They were welcomed almost unconditionally”, and free to do as they pleased, as long as they did not fight each other and avoided “using Transkei as a springboard to launch attacks against South Africa”. This last instruction would, over time, become increasingly honoured in the breach.

While MK and Apla had been pushed back to bases in Uganda and Tanzania by the end of the 1980s, from 1990 onwards they had a safe haven from which to operate in the heart of South Africa itself. It had been a dream of MK since the 1960s to establish bases in the Transkei, and now this had been realised, with the arsenal of the TDF also at their disposal.

MK and/or Apla would soon be using the homeland as a springboard for armed attacks into southern Natal and the Midlands, the Orange Free State and the Eastern Cape. These operations would eventually extend to targets in Cape Town, Johannesburg and elsewhere. Transkei Defence Force weapons would be used in many of these operations.

An undeclared civil war

In March 1992 De Klerk defeated the right wing politically when over two-thirds of white voters endorsed in a referendum the continuation of his reform process “which is aimed at a new Constitution through negotiation”. He followed this up by forcing the retirement of a number of senior police and military officers in the second half of the year; and in an effort to get the negotiations re-started, side-lined Inkatha in the negotiation process, and acceded to a series of critical demands from the ANC.

In his 1998 journal article on the “Third Force” political scientist Stephen Ellis noted that the types of attack “most characteristic” of covert state units seemingly “declined after mid-1992”. This did not mean the end of the activities of covert operatives but rather their “privatisation,” with De Kock, for one, joining and supplying a great quantity of arms to Inkatha after he had been pensioned off from the police in early 1993.

“Many senior military and police officers by this time”, Ellis notes, “had utter contempt for De Klerk and his ministers.” There was an effort by the former securocrats to build an anti-ANC alliance, incorporating Inkatha, the Afrikaner right wing, and some of the homeland governments. The ex-generals remained in close contact “not only with each other but with former colleagues who were still serving in the security services.”

There was also now a convergence in approach between the two sides in this conflict. Inkatha sought to emulate the ANC model by setting up its own combat units – named “Self-Protection Units” in line with the strictures of the National Peace Accord – by providing weapons training to Zulu youth at Mlaba adjacent to Umfolozi Game Reserve. Inkatha also shifted away from spectacular massed assaults of before to less conspicuous operations.

In 1991 there were 14 693 murders reported to the SAP, with SAIRR attributing 2 706 of those to political violence. In 1992 the number of murders reported by the SAP was up to 16 067, with the number of politically related deaths up to 3 347.

The use of covert and pseudo-operations to fight this undeclared war, as well as the intense propaganda campaigns that clouded around it, means our understanding of it remains limited. An assessment that may be true of one time and place in the conflict, may be misleading for another.

In his 2012 book External Mission: The ANC in exile Ellis made the point that all “institutional organisers” of political violence of the early 1990s “claimed that they were simply helping people defend themselves against the other side. In the present state of research, it remains unclear which of them was on the offensive at any given moment, and how high up the political hierarchy the responsibility went.”

The criminal, the racial, and the political

If one turns to the SAP’s statistics and other sources, there was a noticeable deterioration in the crime situation in 1990. The number of reported robberies rose by 20,7% from the year before, to 61 132 nationally. The number of whites murdered, also jumped by 48,5% to 453 in 1990. This was also the last year the police in South Africa provided such a racial breakdown of murder and crime victims.

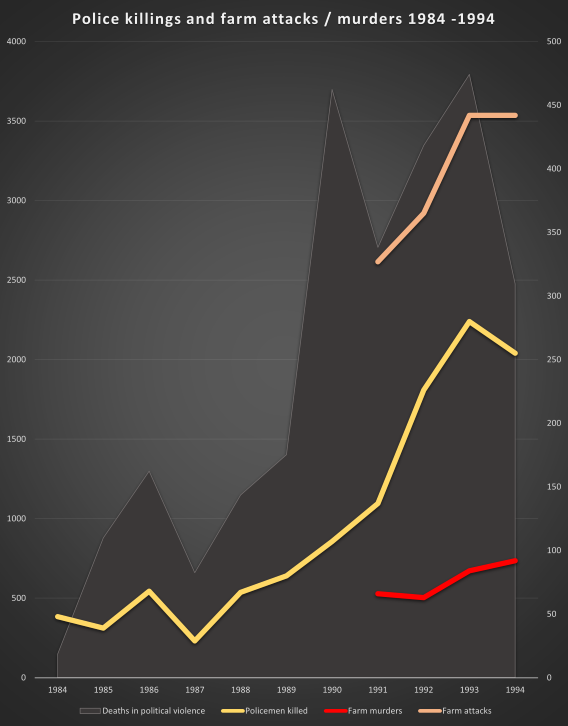

In 1990 the number of policemen – black and white - killed on active duty rose to 107, up from 80 in 1989, and 67 in 1988. The number further increased to 137 in 1991. From late May to early July 1990 there was extensive reporting on a spate of murders and attacks by “armed bands” in white, Coloured and Indian farming communities in the once tranquil Midlands region of Natal, notably in areas around Ixopo, Eston and Richmond.

The following year there were reports of similar outbreaks of this kind of violence in rural areas of the Cape province bordering the Transkei, as well as in the OFS, in areas close to the Transkei (Sterkspruit) and the Lesotho border. From 1991 onwards the South African Agricultural Union would start counting farm attacks across the country and the many murders that resulted.

The political mayhem of the early 1990s led to a broader breakdown of law and order, and the further decay of state authority, which criminal elements exploited. A great deal of the “criminal” violence of the early 1990s occurred in the murky intersection between the political and the criminal. The state, revolutionary and counter-revolutionary violence of the mid-1980s led to the destruction of old moral certainties as well as the authority of elders, tearing apart the moral and social fabric of many township communities.

The ANC and PAC policy of recruiting young men inclined to violence, organising them into armed bands, and providing them with guns was asking for trouble when it came to violent crime. Indeed, from the start many of the ANC’s self-defence units were, Ellis noted, notoriously “ill disciplined, and some were indistinguishable from criminal gangs”.

There was also a strong political and ideological impetus behind this turn to criminality. It was the PAC’s view that the land and its resources had been violently usurped by the white minority. It was Apla's responsibility therefore “to repossess what rightfully belonged to the oppressed and dispossessed” of the black African majority. This did not make them robbers, however, as robbers were “those who steal and defraud and not those who repossess what rightfully belongs to them”. Apla cadres were trained in how to conduct armed robberies in their camps in Tanzania. Once back within South Africa’s borders and operating from the safe haven provided by the Transkei, Apla “repossession units” would pursue racialised armed robberies across the country in the early 1990s.

MK’s approach was far less explicit, given the political sensitivities of the early 1990s, but not wholly dissimilar. Ideologically, MK cadres had long been taught that all their sacrifices for the struggle would be redeemed following the forcible seizure of power when all the wealth “stolen” by the whites – including the farms, the mines, and the factories - would be “returned to the people”. As noted in the first article in this series, Hani, as Political Commissar, incited MK’s auxiliaries in 1986 to rob white homeowners, businesspeople and farmers of their weapons and turn these on the “enemy”.

After the downfall of Communism in 1990, MK struggled to replace the money and weapons previously provided by its East Germany and Soviet allies. To be sure, the ANC continued to receive substantial donations from Western countries, but these were not intended for military purposes, especially not in a period when the armed struggle had supposedly been suspended. A highly consequential decision appears to have been quietly taken at some point in 1991 that MK and the SDUs should use armed robbery to secure weapons and funds for their operations inside the country.

In TRC amnesty hearings three senior MK commanders, based in different parts of the country, related that Hani, who had served as MK Chief-of-Staff up until the end of 1991, had told them to use their own “initiative” to secure weapons from policemen and farmers, and money from wealthy whites.

In 1992 a senior MK commander in Umtata, Phumlani Kubukeli - who reported directly to Hani and also served as his personal bodyguard and assassin - was arrested and convicted for robbing Wiers Cash and Carry in Engcobo, Transkei. As the amnesty committee related in its decision:

“As part of his functions, the applicant had to train recruits in the use of weapons and was also responsible for providing food for the recruits during training. It seems that the Umtata division of MK had budget constraints and the required training was being stifled because of a lack of funds needed to purchase firearms and food for the process. As a result of the precarious financial position, the matter was discussed with the chief of MK [Hani] and it was decided that alternative means, including robbery, in order to obtain the required finance, should be employed. The proviso was that there should be no loss of life and the target should be that of rich white people.”

It was clear, the amnesty committee concluded, that the robbery and related offences “were committed for political reasons” and amnesty was granted to Kubukeli and his accomplices.

There were so many such similar cases that the TRC was forced to rule on the subject in Vol 6 of its Final Report, which states that “while robbery remained contrary to ANC policy, the ANC turned something of a blind eye to acts of robbery for operational purposes – that is, robberies to secure weapons or money for logistics.”

This all made it difficult or impossible for the ordinary observer to tell whether a particular robbery or murder was political or criminal. Confusing the matter further its status could change over time, depending on the political circumstances. An MK or SDU commander may have been given the green light to use robbery in the early 1990s. If he had the bad luck to be caught the ANC would disown his actions as stemming from “ill-discipline”. But when applying for amnesty post-1994 it would be quietly conceded that “yes, this was allowed” and amnesty could then be granted on this basis.

Alongside policemen farmers were historically at the top of the target list for MK and Apla. They owned weapons, they were enforcers and beneficiaries of the existing system, and their elimination would steadily expand the “space” in which combat units could freely operate.

There was a huge escalation of attacks and murders on farms from early 1990 onwards and by 1992 these had already reached epidemic proportions, with the Orange Free State particularly hard hit. The ANC disowned responsibility for attacks on white farmers both then and before the TRC but in several cases, members of its combat units sought – and were granted -- amnesty for farm attacks, mostly based upon the informal instruction they had received to use robbery to secure weapons and funds.

Apla for its part would freely admit to a policy of using terror to drive white farmers off the land in the early 1990s. These operations were mostly launched across either the Lesotho or Transkei borders. In his memoirs the Apla commander Letlapa Mphahlele reminisces about the success of this campaign:

“As Apla mounted attacks on fertile and rich farmlands occupied by European settlers, farms lost their value and some farmers hastily sold to wealthy Africans. A farm that was once owned by a white man with an Afrikaans or English name now displayed a freshly painted African name. This development complicated the planning of operations by Apla cadres, because their orders were to attack white farms and spare those owned by Africans.”

The amnesty committee of the TRC would later receive “a total of twenty-seven applications from PAC and APLA members for attacks on farms, all committed between 1990 and 1993. A total of twelve people were killed and thirteen injured in these attacks. The Amnesty Committee granted all but four of the applications.” It is important to note that Apla and MK amnesty applications did not cover all such incidents, but generally only those where the culprits had already been linked by police to the crime, and usually were in jail for it.

1992 saw a further escalation in these forms of criminal violence. All told, 226 policemen were killed that year, and the number of robberies reported to the police increased to 78 664, up from 61 132 in 1990. The number of cases of people being attacked in their homes increased from 1 133 in 1991 to 1 688 in 1992, an almost fifty percent increase, and over three times the number recorded by the SAP in 1987.

In late 1992 Apla operatives, often based in the Transkei and armed with weapons provided by Transkei’s army or special forces, became far more aggressive in taking the war into white areas. Operatives targeted gatherings of white civilians such as in the attack on the King William’s Town Golf Club on 28 November 1992 in which four civilians were killed and seventeen injured.

Hani’s assassination

The assassination of Hani by the fanatical Polish anti-communist Janus Walus in April 1993 was intended to provoke outright racial war, but this was avoided through exceptional leadership from Nelson Mandela. This was the moment that, as Malala recounts, authority over South Africa and the ability to determine its future would pass decisively from FW de Klerk to Nelson Mandela.

The message delivered by Mandela to the nation, broadcast on SABC, was that we “must not permit ourselves to be provoked by those who seek to deny us the very freedom Chris Hani gave his life for… Let us respond with dignity and in a disciplined fashion.” By not directly retaliating the ANC avoided the escalation that some in the right wing had hoped for. Instead, it used this moment of crisis – and the NP’s panicked fear of full-scale insurrection - to secure an election date, and ultimately push through a political settlement on terms that would allow it to have the decisive say over the drafting of the final constitution.

Though Malala’s book is subtitled “the week Mandela averted civil war,” the reality was that the following year would see a sharp escalation in political carnage. The armed wings of all political factions – Afrikaner right wing, the dying apartheid state, Inkatha, ANC and Apla – redoubled their bloody efforts to block or speed up the transition. Apla further escalated its operations, massacring civilians in St. James Church in Kenilworth Cape Town, on 25 July 1993, and the Heidelberg Tavern in Observatory Cape Town on 31 December that year. They also started conducting guerrilla attacks against state and strategic targets with weapons provided by MK. There were also indiscriminate terrorist attacks by Afrikaner right wingers against the black population.

Between May 1993 and April 1994, 4 627 politically linked fatalities were counted by the SAIRR. These killings formed a subset of the 19 853 murders recorded that year by the SAP (so excluding the homeland areas), the most ever – and double that of 1987. The completeness of these murder numbers is open to question, given the mayhem of the period, but it seems safe to assume that the SAP was able to count its own casualties: 280 policemen were killed in 1993, a number four times higher than in 1988. The SAAU recorded 84 farm murders, up from perhaps a handful in 1988, that had resulted from 442 attacks. The number of recorded robberies reached 87 102 in 1993, close to double the 1988 figure. 68 150 armed robberies were recorded in 1994, a figure two-and-a-half times higher than in 1988.

The centre reasserts itself

In the run up to 27th April 1994 election the ANC leadership, with Thabo Mbeki playing the key role, really did narrowly avert an imminent civil war as they cut a series of separate deals with the South African Defence Force, the military men of the Afrikaner right wing, led by General Constand Viljoen, and with Inkatha; by the time the election was held all these actors had been drawn into the political process.

The ANC secured 62,65% of the vote, giving it an overwhelming democratic mandate, and ushering in three-decades of electoral dominance. It was joined in the Government of National Unity by the NP which won 20,39% of the vote, and the IFP which secured 10,54%, as well as a majority of the vote in KwaZulu-Natal. The Afrikaner right wing were represented in parliament by the Freedom Front led by General Viljoen after it won 2,17% of the vote. The PAC meanwhile secured a mere 1,25% of the vote.

Following the election there was a dramatic fall off in political violence, as reflected in the SAIRR’s count of political fatalities. These were running at 367 per month in the first four months of 1994, but then fell to an average of only 125 per month for the rest of the year. The number of reported murders fell back to 18 312. As Fairbanks observes through Dipuo’s experience this would be reflected in a dramatic fall off in violence in areas like Katlehong. “For the first time in her life”, Fairbanks writes, “Dipuo felt comfortable walking down Khumalo street, Katlehong’s main drag.”

Having stared into the abyss each side now pulled back from the brink. The commanders of the right-wing military faction, whom the ANC probably feared most of all, told their men to stand down. Mbeki, newly elected Deputy President and Mandela’s heir apparent, sought to send a similar message to the liberation movement’s more disordered and ill-disciplined forces.

In an August 1994 discussion document he wrote that “It is imperative that we deal firmly and decisively with violence originating from within our ranks whether directed against competing political parties or other members and supporters of the movement… We must move away from the pretence that such violence does not occur or that it is so insignificant that we should not be concerned about it.”

The war between ANC and Inkatha in KwaZulu-Natal persisted but gradually wound down in the second half of the 1990s, before Mbeki was finally able to put an end to it. Mbeki would also engineer the expulsion of Holomisa from the ANC in 1996.

When it came to the concerns of the white minority the ANC tread softly in the 1993 to 1995 period as it sought to ward off the threat of counter-revolution and get its hands firmly onto the levers of state power. Serving members of the civil service and security forces were reassured, by Mbeki and others, that their skills and expertise were needed and valued by the new government.

There was a reassertion too of the rule of law when it came to state perpetrators of wrongdoing. The long running counter-intelligence investigations approved by FW de Klerk into wrongdoing by covert units of the police and the military now culminated in prosecutions being brought by the Transvaal Attorney General’s office against Eugene de Kock, Wouter Basson, Magnus Malan, and others.

This was the famous period of the “political miracle” and the “birth of the Rainbow nation”. It was at this happy point that Western audiences turned off the television set and stopped paying much attention to developments in South Africa.

What happened afterwards is dimly remembered and now highly contested.

This will be the subject of the next instalment.

This article first appeared on the Konsequent Substack.