Racial inequality declines to its lowest levels yet

A Stellenbosch University study shows a rapidly growing black middle class and a dramatic decline in racial inequality, but cautions that opportunities and life chances for children from different communities still remain unequal.

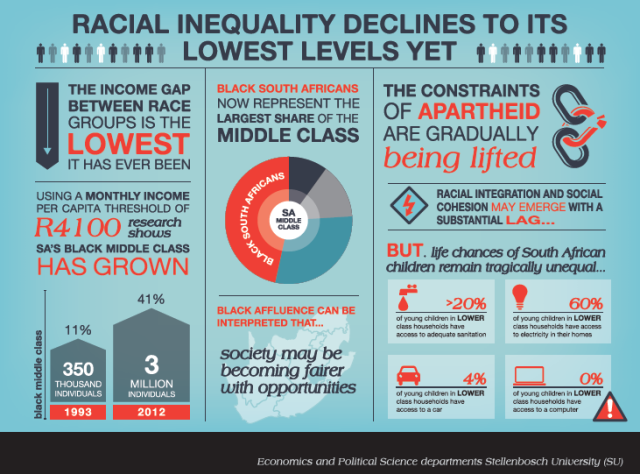

According to a comprehensive two-year long interdisciplinary study by researchers from the Economics and Political Science departments at Stellenbosch University (SU) the income gap between race groups is the lowest it has ever been (see here).

"In terms of fundamentals, our society is slowly becoming more equitable," says Prof Hennie Kotzé, Research Fellow at the Centre for International and Comparative Politics at SU.

"That is not to justify the pace of change, but rather to dispel possible misconceptions fuelled by recent evidence of social fragmentation and racial tensions. While there is certainly still room for improvement, data on the incomes and characteristics of South African households suggests that we are making steady progress."

Using a monthly income per capita threshold of R4 100 (in 2012 prices) the researchers found that South Africa's black middle class has grown from 350 000 individuals in 1993 to almost 3 million individuals in 2012. Over this period the black share of the middle class has grown from 11% to 41%.

"The survey data shows a continuous downward trend in racial income inequality since 1993 and at the same time also a dramatic surge in black affluence. Previous studies on emergent black affluence often focussed on the implications for the consumer market, but said little about the impact on the social and political landscape. The disassociation of race and class is creating a post-apartheid society that is more dynamic and more equitable," says Kotzé.

Kotzé was part of the research team which included economists, political scientists, anthropologists and sociologists from SU, the University of the Witwatersrand and Pretoria University. Other team members from SU were Prof Servaas van der Berg and Prof Ronelle Burger from the Economics Department, and Dr Cindy Steenekamp and Prof Pierre du Toit from the Political Science Department at SU.

"After almost 20 years of democracy it is no longer true that South Africa's middle class is mainly white," says Van der Berg, a professor of Economics. "Black South Africans now represent the largest share of the middle class."

"There are indications that the magnitude of this shift and the significance of these developments may previously have been overstated due to media and marketing hype and analysis with small and unrepresentative samples that focus only on the black affluent. However, our work with large representative survey samples affirms that the middle class is becoming more representative," says Burger.

According to Pierre du Toit, "this is a promising sign, with potential positive political, social and economic repercussions".

"Most significantly perhaps, growing black affluence can be interpreted as an indication that our society may be becoming fairer with opportunities increasingly distributed according to the ability and motivation of individuals. Our research shows that gradually the constraints of apartheid are being lifted."

Steenekamp says that "the research cautions against over optimistic predictions of economic growth, political stability or social cohesion" based on this recent surge.

"Marketing hype and a focus on these individuals as consumers have fuelled stereotypes and a characterisation of this group as cohesive and uniform. But our research shows that there is considerable variation within the middle class once you look below the surface."

"While the rise in the black middle class is expected to help dismantle the association between race and class in South Africa, the analysis suggests that notions of identity may adjust more slowly to these new realities and consequently, racial integration and social cohesion may emerge with a substantial lag."

Interviews conducted during the study suggest that despite the surge in black affluence, old apartheid era notions of socio-economic class tying class to race have endured and consequently some educated and rich black South Africans are reluctant to identify themselves as middle class.

"Class identity is complex. Our analysis found that the ‘middle class' label was only weakly correlated with traditional notions of what it means to be middle class. We find some correlation between self-identification as middle class and income, assets and occupation, but not as strong as one would have expected. However, we found no evidence of a distinct set of so-called middle class values. It is simply not true that the middle class has a better work ethic or places a higher value on savings or education. Research in Latin America confirms this. The middle class might think that they are distinct because they value hard work and education, but there appears to be no basis for this and such conceptions could be due to class prejudice," said Steenekamp.

The study provides good news, but does not condone the status quo. While there are signs that race is no longer as dominant as it was before in determining economic advancement, white South Africans are still overrepresented amongst the rich and poverty remains concentrated amongst black and coloured South Africans.

"It is important to highlight that the life chances of South African children remain tragically unequal with opportunities and prospects depending largely on where a child was born and who his or her parents are. Children born in poor communities have limited choices and consequently they are often prevented from reaching their full potential, while the future looks promising for children from upper middle class households with educated parents," said Van der Berg.

Where almost all children growing up in typical upper middle class households will have access to electricity, clean water and decent sanitation we find that less than 20% of young children in lower class households have access to adequate sanitation, less than 35% have access to clean water and just over 60% have electricity in their homes. Similarly, while 83% of children who live in upper middle class households have access to a car, it is rare amongst the lower income classes (4%). The starkest contrast is in terms of computers: 73% of upper middle class children grow up with computers in their home, but virtually none of those born into lower classes have access to a computer.

Additional information and photos:

More information on the multi-disciplinary project on the emerging middle class is available at the Research on Socio-economic Policy (RESEP) website.

Statement issued by Siyavuya Madikane, Ogilvy PR, Cape Town, October 23 2013

Click here to sign up to receive our free daily headline email newsletter