GOING TO THE ROOT

DISCUSSION DOCUMENT ON THE SECOND, MORE RADICAL PHASE OF OUR TRANSITION

SACP

A radical second phase of the National Democratic Revolution -its context, content, and our strategic tasks

("radical adj relating to, constituting, proceeding from or going to the root..." The Chambers Dictionary). SA's triple crisis - the immediate context of the call for a second radical phase of the NDR.

Two decades beyond the critical 1994 democratic breakthrough our society remains afflicted with crisis levels of unemployment, inequality and poverty. This triple crisis has some cyclical features, reflecting the impact, for instance, of the 2008 global crisis on our own economy. But even during periods of relatively strong domestic growth in the late 1990s and early 2000s, crisis levels of unemployment, inequality and poverty persisted. Our core social and economic challenges are clearly deep-rooted and systemic - rather than the result of a temporary downturn. This means that our response cannot just be a question of waiting for, or seeking to stimulate an upturn in growth along the same path dependent direction as in the past.

It was in this context that the necessity for a radical second phase of the NDR was debated and endorsed at the ANC's National Policy Conference (June 2012) and formally adopted at the ANC's Mangaung 53rd National Conference (December 2012). The resolutions of the Alliance Summit sought to give further content to the concept. The call for a second radical phase was also the overarching theme of President Zuma's 2014 inauguration speech.

The triple crisis is reflected in rising popular discontent, a growing sense of alienation, frustration and sometimes despair amongst significant strata of the youth, the unemployed, the working poor, those in informal settlements, and the so-called "black middle class" (most of whom are working class professionals or self-employed and often struggling petty entrepreneurs). In short, the triple crisis is being felt acutely across a broad spectrum of the waged and unwaged popular strata.

The unprecedented numbers of so-called "township service delivery protests", and the lengthy and violent platinum belt strike are further symptoms of the impact of this crisis. Notwithstanding the ANC's impressive May 2014 electoral majority, it is critical that we recognise there is a popular, but for the moment largely amorphous, groundswell of frustration - much of it currently beyond the reach of the ANC-alliance's organisational and ideological influence.

This is the immediate context of the call for a second radical phase of the NDR as a programme that strategically combines state power and popular activism. But this call (this "narrative" about the way forward) is not the only "narrative" competing for hegemony in the current reality. Indeed, the perspective of a second radical phase of the NDR remains undeveloped. It is often poorly or confusingly explained, and other competing perspectives often enjoy greater prominence in the media and broader public domain.

This present intervention seeks to contribute to a collective discussion on the meaning, content and context of a second radical phase of the NDR.

Why do we speak of a SECOND radical phase of the NDR?

The ANC National Policy Conference correctly clarified that we are not speaking about a second "stage". Implicit in this clarification is the recognition that we are not advocating a break with the current constitutional dispensation (or with a supposedly "illegitimate government" requiring regime change) - of the kind that the EFF and others appear to be flirting with. But nor are we advocating for a back to business as usual. Rather, we are underlining the imperative of a new phase in an ongoing national democratic transition.

This means that, if we are to give content and context to a second phase, we need also to characterise the main content and limitations of the first phase.

So what was the first phase of the NDR?

The first phase was essentially played out on the political and juridical terrain. It had as its critical moments:

* the 1991-1994 multi-party negotiations that finally compelled agreement (largely forced through mass mobilisation) that a future constitution could only be drawn up by a democratically elected Constituent Assembly;

* the 1994 democratic electoral breakthrough itself; and

* the consequent 1996 adoption of a new constitution.

These processes were then consolidated in a wide-range of laws, democratic institutions, and the deracialisation of the administrative apparatus of the state. It is important to assert that the first phase was itself radical. It abolished (politically, juridically, constitutionally) white minority rule.

Thanks to the active role that the organized working class had played in the defeat of the apartheid regime, there were many important legislative and institutional gains made by the working class after 1994. The explicit entrenchment of worker rights in the Constitution, a range of progressive labour laws including the Labour Relations Act and the Basic Conditions of Employment Act, and the institutionalization of NEDLAC.

The first phase has also been the platform on which a massive socioeconomic REDISTRIBUTIVE programme has been launched.

Over the past 20 years, the democratic breakthrough of the mid-1990s has been used by four successive ANC-led administrations to drive major REDISTRIBUTIVE socio-economic programmes.

Among the notable achievements have been:

* More than 16 million (nearly one-third of all South Africans) are now benefiting from a range of social grants - up from 3 million in 1994;

* Over 7 million new household electricity connections have been made since 1996. (To put this achievement into context - in the preceding century, successive white minority regimes only electrified 5 million households!);

* Over 3,3 million free houses have been built, benefiting more than 16 million people;

* More than 1,4 million students have benefited from the National Student Financial Aid Scheme;

* Over 9 million learners in 20,000 schools receive daily meals.

* Over 400,000 solar water heaters have been installed free on the rooftops of poor households in the past 5 years - one of the largest such programmes in the world.

There are many other major redistributive achievements in sanitation and water connections, in adult basic education, in Grade R school enrolment, in rolling out retro-virals, and much more.

These are all part of the "good news story" that the ANC alliance in the last elections quite correctly campaigned upon. These real achievements are certainly the most important factor in the continued overwhelming majority electoral support achieved by our movement.

Of course, since we are dealing with a real life process and not an abstract theory, this massive redistributive process underway since 1994 has often been uneven. Targets have often not been met; the quality of "delivery" has sometimes been poor; maintenance of new infrastructure often gets neglected. There have been challenges of corruption, some of them serious. What is more, in the face of poverty, unemployment and inequality the redistributive process is never enough and is often overwhelmed by the scale of the challenges. Housing backlogs seem to grow as fast as we build new RDP houses - partly because new housing projects act as magnets to draw ever more people from outlying informal settlements and rural poverty into areas of development.

The anti-majoritarian liberals, opposition parties, the commercial media dwell incessantly on all of these problems. Their strategic objective is to sow popular demoralization and a lack of belief in the capacity of popular forces and the democratic state to advance development. In the face of this ongoing offensive, it is important that we do not become overly defensive or in denial about the many challenges. In particular, we need to deal decisively with corruption and incompetence.

But even more importantly we must not allow this offensive to distract us from getting to the root of the matter: Why, despite a massive redistributive programme over the past 20 years, are crisis levels of unemployment, poverty and inequality still being reproduced?

To answer this question is also to answer our main question: What do we mean by (and why do we need) a second radical phase of the NDR?

The main thesis of this intervention is that, with all of its achievements, the key limitation since 1994 has been two-fold:

1. There has been socio-economic RE-DISTRIBUTION but insufficient STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATION particularly of the systemic features of our PRODUCTIVE economy

2. This redistributive effort has been almost entirely conceptualized as a TOP-DOWN STATE "DELIVERY" PROCESS

Redistribution - but insufficient structural transformation

Over the past 20 years our major emphasis on the socio-economic front has been on REDISTRIBUTION.

Redistribution is, and must continue to be, a key pillar of our NDR. BUT THE EMPHASIS ON REDISTRIBUTION HAS TENDED TO NEGLECT THE CRITICAL TASK OF TRANSFORMING the systemic features of SA's PRODUCTIVE ECONOMY. We have tried - and not without important successes - to redistribute surplus (largely through the fiscus). But these fiscal resources are derived from a portion of the surplus produced by an untransformed productive economy that is locked into a highly problematic growth-path trajectory. It is precisely this untransformed productive economy that is the prime factor in reproducing the often deepening levels of unemployment, poverty and inequality that valiant efforts at redistribution seek to address. Moreover, some of the redistribution has tended to actively strengthen incumbent private monopoly capital.

BEE - giving a democratic government a foothold in business, or business a foothold in government?

Black Economic Empowerment measures have also largely been of a REDISTIBUTIVE nature - apportioning encumbered shares to aspirant black capitalists, usually with political connections. While the complexion of the board-room might change, it is not clear whether it is the newly "empowered" who change the ethos of the board-room, or it is the board-room that changes the ethics of the newly "empowered". Worse still, some major BEE deals have involved South African blacks fronting for foreign importing companies in deals that end up displacing local jobs and local investment.

Overwhelmingly BEE measures have been used adroitly by South African monopoly capital as a means of re-gaining its influence and foothold within ruling circles after the demise of white minority rule. In this respect they are part of the general weakness of the first phase of the NDR. Their largely redistributive character has produced change without transformation.

Corruption - another variant of redistribution, and another capitalist means to achieving a foothold within the democratic state (and political and labour formations)

Corruption is another, and particularly corrosive, counter-revolutionary form of unproductive redistribution. There are many factors behind the levels of corruption currently plaguing our society - but one of these that is too easily forgotten is, precisely, the conundrum that confronted monopoly capital after 1994.

It no longer enjoyed the same level of assured access to the ruling elite. While capitalists in general will tend to criticise corruption in general (it is a cost to business and therefore to profitability), as INDIVIDUALS or as INDIVIDUAL corporations in competition with other corporations for tenders and favours, the corrupting of public officials easily becomes routine practice. This is a particular danger where there is an old established economic elite and a newly arrived (or different) political elite.

In saying this we are not shifting all blame for corruption on to the private sector, nor are we are remotely excusing corrupt behavior within the state, or within our own political and trade union formations.

On the contrary, we should expect much higher levels of ethical probity from those committed (at least in theory) to the public interest and to a national democratic revolution. However, it is important to understand and deal with the plague of corruption not only from a purely subjective and ethical standpoint, but also understand and therefore deal decisively with its systemic features.

The second key weakness of the first phase of the NDR has been that:

Our major socio-economic redistributive efforts have been almost entirely conceptualized as TOP-DOWN STATE "DELIVERY" programmes.

Our popular mass base has been turned into "beneficiaries", "recipients", "clients", "customers" of redistributive state "delivery" - and NOT active participants, not "motive forces", not productive protagonists of transformation. Individual entitlement rather than collective responsibility has often become a prevailing attitude. These dynamics have, in turn, produced three related problems:

* As government's massive redistributive effort gets overwhelmed by the scale of problems, or falls behind rising and often legitimate expectations, or fails to "deliver" equally at the same time to everyone - so popular anger turns on government. The top-down redistributive "delivery" model based on always insufficient fiscal resources sets up government as a sitting duck target for anger and frustration - while monopoly capital disinvests and largely escapes blame. In fact, monopoly capital funds the diversionary ideological assault on government's "incompetence" and "corruption" (while often colluding, precisely, with this corruption).

* The tendency to transform our popular mass base into individual or household "beneficiaries", "recipients", "clients" of government delivery also tends to undermine the potential cohesion of poor communities. Many "township delivery protests" are fuelled by factional rivalries within communities - backyard dwellers versus shack-dwellers for priority listing on the housing list; competing taxi associations for operating licences on new routes; local small businesses against each other and against non-South African traders. These inward-turning, intra-township rivalries contaminate and are contaminated in turn by local politics - with all of the familiar problems of patronage networks, factionalism and tenderpreneuring.

* The effective de-mobilisation of popular forces by the top-down, state "delivery" model of redistribution has also deprived us of an important means of transforming the state itself. The Freedom Charter's call not just for one-person one-vote representative democracy, but also for "DEMOCRATIC ORGANS OF SELF-GOVERNMENT" - i.e. for various forms of ACTIVE PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY has been largely lost. Since 1994 we have nominally introduced a wide range of statutory institutions and practices implying participatory democracy - community police forums, school governing bodies, ward committees, municipal participatory budgeting, etc.

However, in practice most of these are non-functional, or are captured either by political functionaries, or by middle-class interests and used to preserve existing privileges. Yet, organs of popular participatory democracy are potentially our best weapon for transforming the state, and overcoming inherently negative features - bureaucratic silos, officiousness and indifference on the part of state functionaries, technocratic aloofness, and, above all, corruption.

In summary, the first phase of the NDR marked a radical politico-juridical break with the past - it abolished white minority state rule. The achievements of this first phase need to be continuously advanced, deepened and defended. However, the redistributive emphasis of this first phase was insufficiently complemented by (or integrated into) a radical programme of transformation of our productive economy and the systemic social, economic and spatial features that support its growth path dependency.

These are features that continue to reproduce crisis levels of unemployment, inequality and poverty (as well as corrosive realities like embedded corruption). Moreover, the emphasis on a top-down, state "delivery" of redistribution has effectively demobilised the key popular bloc of forces, re-routing energies into individualistic advancement, factionalism, or anti-government frustration.

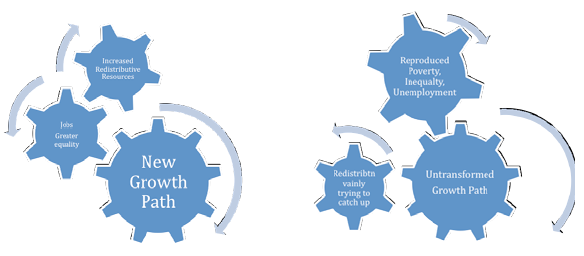

Instead of a Virtuous Cycle in which the Growth Path is job creating, poverty alleviating and more egalitarian and therefore also creates additional resources for redistribution:

Instead of this we have:

In the next section we pose the basic and critical question:

What are the "roots", the problematic systemic features of our productive economy that continue to reproduce crisis levels of unemployment, poverty and inequality?

To answer this question, it is useful to revisit the concept of Colonialism of a Special Type (CST).

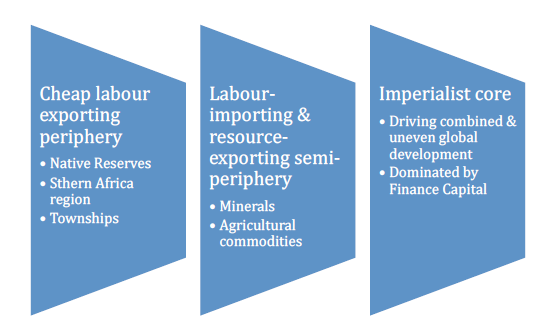

In the first place, it is important to remember that industrial capitalism did not emerge organically within SA. It was an imperialist-driven and externally imposed process in the late 19th century. From the 1910 formation of the Union of SA, the nation-state we still call SA, exhibited two colonial-type core/periphery articulations, two relations that both involved marginalisation AND simultaneous subordinate inclusion of the marginalised:

* An "internal", "racialised" articulation or relationship between a white minority bloc and a brutally dispossessed (i.e. proletarianised) black majority, marginalised into "native" reserves and later urban townships as a huge pool of under-employed, a reserve army of labour - forced to sell labour power on a distant capitalist market

* An "external" colonial relationship establishing the semi-peripheral positioning of SA's emergent capitalist system. This involved SA's incorporation into but subordination within the global imperialist accumulation chain - essentially as an exporter of primary commodities (mainly minerals) produced on the basis of super-exploited (cheap/black) labour;

The internal colonial-type articulation was grounded through the first half of the 20th century in an "internal" core/periphery relation between what Harold Wolpe insightfully analysed as "an articulation between two modes of production" - an advanced industrial capitalist mode centred on mining, on the one hand, and subsistence farming based in a patriarchal mode in the reserves (and wider southern Africa), on the other. At the heart of this core/periphery relationship was the reproduction (in the subordinate mode) of "cheap" migrant labour for the industrial core.

By mid-20th century the centrality of this version of the "internal" colonial articulation was considerably under strain with the exhaustion of the productive capacity of the reserves, the growth of secondary industry in SA, especially during the war years, and increasing black urbanisation.

"Apartheid" should be seen as a relatively successful, four-decades long, capitalist driven perpetuation of the earlier internal colonial articulation that had been underpinned by two modes of production. The apartheid regime sought, on the one hand, to preserve this articulation by sustaining the marginal productivity of the reserves through land-care and agricultural extension work, and the strengthening of patriarchal subordination of those in the reserves - with the consolidation of the repressive Bantustan apparatus. However, greater focus now shifted to urban forced removals and the mass construction of peripheral urban black townships developing a new form of labour migrancy - daily migrancy - that perpetuated the simultaneous exclusion and inferior inclusion of the black majority.

It is the combination of these two colonial-type articulations (an internal and an external relationship) in their inter-dependence that lies at the heart of what might be described as colonialism of a special type. For a variety of reasons, through the 1990s, the external, imperialist-imposed, semi-peripheral sub-ordination of SA within the global capitalist system was under-emphasised within our movement.

Advancing a second radical phase of the NDR requires that we now re-surface more clearly the IMPERIALIST dimension of our persisting structural problems:

By approaching SA's politico-economic history through the lens of CST we help to locate the the systemic legacy features we are dealing with in the context of a world capitalist system with its inherent tendencies towards combined and uneven global development, or development and underdevelopment, core and periphery. This helps to avoid several illusions that have had a negative impact on our ability to accurately chart a strategic way forward in the post-1994 reality.

The concept of "imperialism" disappeared from official ANC programmatic documents in the 1990s and early 2000s. Linked to this vanishing act was the exaggerated "exceptionalism" attributed to apartheid and the related view that apartheid was essentially all about "racism"- which it partly was, of course, but with "racism" becoming de-linked from any objective and systemic socio-economic realities. While SA, like any social formation, has its own unique features, the notion that "apartheid" was absolutely unique globally played into the 1990s neo-liberal "end of history" narrative. With apartheid abolished (and the Soviet bloc disintegrated), SA was seen as "returning to a happy family of nations" - "normality" was restored.

Understanding SA's political economy legacy as the legacy of a colonial variant of combined and uneven development in the imperialist era, i.e., as a local variant of a wider and persisting global imperialist reality, helps to explain why the end of apartheid hasn't produced domestic (or global) "normality".

While it is no longer appropriate to describe the post-1994 SA as a case of CST, most of the core systemic features hard-wired into SA's subordinate capitalist growth path remain. These key features are systemic in the sense that they are inter-related, inter-dependent and mutually self-reinforcing.

They are:

* The continued subordination to the imperialist core of SA's political economy as a semiperiphery within the global division of labour;

* The domestic dominance of the minerals-finance monopoly sector tied into global financialisation - with an historically under-developed manufacturing sector, in particular;

* The existence of a highly monopolized financial sector dominated by four large banking oligopolies;

* High levels of monopoly concentration across all sectors - with an historically underdeveloped SMME and co-operative sector;

* Stark spatial inequalities, a symptom of the pattern of development / under-development - between SA and its southern African neighbourhood; between urban centres and rural areas within the country; and in the persisting urban apartheid legacy. These spatial realities continue to be hard-wired into the energy, logistical, and built environment infrastructures of our country and region;

* The education and training system (which we are still struggling to transform), remains a critical element in the reproduction of racialised inequality, and specifically of the reproduction of a reserve army of unskilled and semi-skilled workers; and

* A productive trajectory that is energy-intensive, with its origins in the mining revolution, that continues to recklessly plunder our natural resources and damage the environment.

It is important to underline that these are not random elements but systemic features that remain a deep-rooted legacy. They are the systemic features of South African capitalism that, in mutually reinforcing each other, tend to lock our society into a persisting and problematic path dependency.

Precisely because they are systemic, any attempt to transform one of these aspects (for example a transformed education and training system) without simultaneously addressing the others (including, for instance, significant re-industrialisation to employ graduates and artisans) is likely to end in frustration and failure.

Paradoxically, in many ways these problematic features of SA's productive economy have been further entrenched since 1994.

This has been the result of:

* The power, mobility and strategic capacity of monopoly capital;

* Global economic developments;

* Poor economic policy choices, weak capacity and a lack of strategic discipline on the part of government; and

* The weakening of popular activism and particularly weakening of the progressive trade union movement, the result, in part, of a major (radical in its own way) capitalist-driven restructuring of the work-place and the labour market.

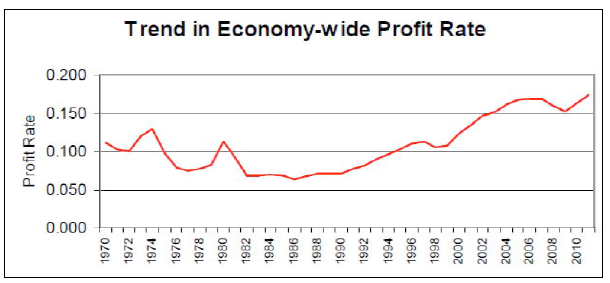

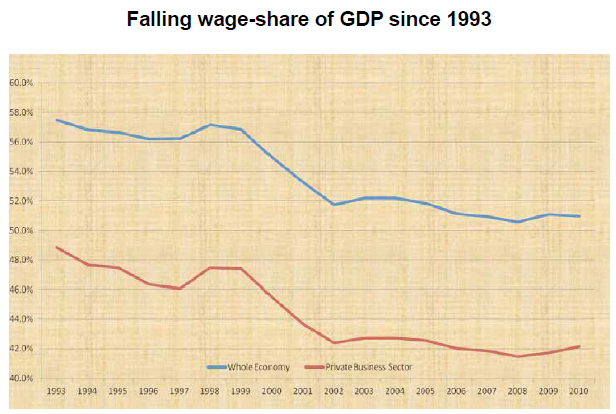

Notwithstanding the democratic break-through of 1994 and the major redistributive programme of government, the balance of class forces has shifted unfavourably over the past 20-years for the working class and poor. Private monopoly capital has been the principal beneficiary of our hardwon democratic breakthrough. Private monopoly capital has used our democracy and the ending of apartheid-era sanctions to dramatically increase its profit rate, to appropriate a growing proportion of surplus for profit at the expense of workers' wages and at the expense of fiscal resources, and has failed to significantly re-invest profits into productive investment within our economy.

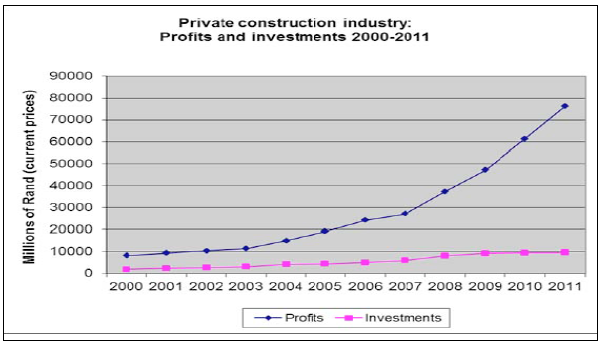

These trends are clearly illustrated in the following three Tables:

Table 1: Profit rate in SA, 1970 - 2011 (Profit rate = total net operating surplus relative to total capital stock (Source: Dick Forslund, AIDC)

Table 2 - Falling wage share of GDP in SA since 1993 (source Forslund, ibid) SACP3

Table 3 - StatsSA for "Gross operating surplus" & SARB for "Gross fixed capital expenditure" - (Source, Forslund, ibid)

Table 3 reflects the growing disparity between profits earned by the construction sector and actual fixed investment made back into infrastructure. This is particularly notable given the fact that there has been considerable public sector investment in infrastructure in the run-up to the hosting of the 2010 FIFA World Cup, and in the 2009-2014 fourth ANC-led administration in which over R1-trillion was invested in infrastructure. The growing disparity between private sector profits and private sector investment in SA is likely to be even greater in other sectors.

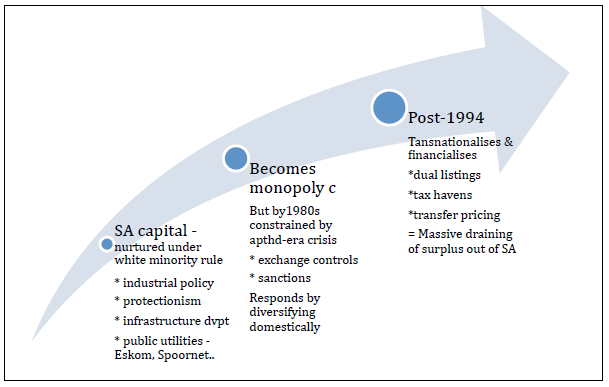

These tendencies, which have dramatically increased since 1994, have been driven by both external and internal realities:

* General global capitalist restructuring over the past three decades - involving increased transnationalisation of operations, and, especially, run-away financialisation. The latter, a response to the crises of over-accumulation, falling rates of profit, and long-term stagnation in the developed capitalist core, has seen productive economic activity increasingly swamped by speculative financial activity (the global casino economy). This restructuring has resulted in the weakening of trade unions, growing inequality, the rolling back of the welfare state, and the unravelling of explicit or implicit social accords throughout the developed capitalist core.

* In the late 1970s and through the 1980s, SA's financial, mining and other monopoly sectors were considerably locked out of this global capitalist restructuring as a result of anti-apartheid economic and financial sanctions, as well as stringent apartheid foreign exchange controls and other defensive measures. Bottled-up surplus generated within the leading monopoly finance and mining sectors of our economy was invested into diversified activity. Mining houses for instance invested, in this period, into forestry, agro-processing, logistics, retail and manufacturing - stimulating re-industrialisation, local beneficiation and, indeed, a growing industrial base for a resurgent trade union movement. The end of apartheid and the lifting of sanctions marked a dramatic reversal of these processes.

As a result of this rapid and massive process of trans-nationalisation and the expatriation of capital, the democratic South African government now increasingly has to engage former SA monopolies (born and bred within our country and grown rich on massive fiscal support and on the sweat of millions of South African workers) as foreign investors.

Here are just a few examples of how these processes have developed rapidly post-1994:

***

ABSA Bank - one of 4 banking monopolies that dominate SA's financial sector - but who owns it?

Absa's origins are in the early mobilisation of Afrikaner capital. Absa itself was formed in 1991 out of a merger between United, Allied and Volkskas. In 1992 it acquired the Bankorp group including Trustbank.

In 2005 Barclays UK purchased 56,4% of Absa. In 2013 Barclays increased its share-holding in Absa to 62,3% and the name was changed to Barclays Africa Group Ltd. As at June 2013 ABSA/Barclay's Africa shareholders were located in:

* UK - 57,6% * US & Canada - 8,8% * Other countries - 7,4% * SA - 26,2% When Barclay's Africa CEO Maria Ramos calls for a "social covenant" (presumably with government and labour) - where does she derive her mandate from?

***

AFGRI - how a former SA agricultural co-op was bought out by US speculators

Afgri is an agricultural services company dating back 90 years. Originally a co-op supported by successive white minority governments. After 1994, instead of transforming this co-op to service emerging and subsistence farmers, we allowed it to become (like other former agricultural co-ops - KWV, Clover, Senwes) a private company listed on the JSE in 1996. Financial speculation and profit maximisation displaced agricultural production and food security concerns.

In 2014 Afgri was de-listed from the JSE and bought out by a little-known North American based financial speculator group registered in the tax-haven of Mauritius.

But Afgri remains a strategic player in our agricultural sector:

* Owning a vast proportion of South Africa's grain storage capacity, * Providing services to 7,000 mainly commercial farmers through rural-based retail outlets and silos.

* It is the largest supplier of John Deere tractors in Africa.

* It was recently subsidised through governments' tractor support programme for emerging farmers, and it acts as an agent for the Land Bank, distributing some R2bn a year on behalf of the bank.

A critical asset for national food security is now a financialised entity owned by foreign speculators

***

These are just two examples of a major trend underway since the mid-1990s. In the late 1990s Anglo, De Beers, Old Mutual and SAB Miller, Investec, Didata, Gencor, Liberty, etc. were allowed to dual list, in effect moving much of their corporate tax responsibilities, dividend payments and investments offshore.

More recently, furniture giant Steinhoff International received a Reserve Bank go-ahead in July 2014 to move its primary listing to Frankfurt. Also this year BHP Billiton has announced plans to "demerge" most of its local mines into a separate company. Last year Gold Fields unbundled Sibanye Gold. This year AngloGold Ashanti, the third largest gold miner in the world, tried to split its assets into a South African bundle, but was blocked by its own share-holders who were unwilling to fork out R20- billlion to ensure that the South African bundle would be debt-free - a condition correctly set by the Reserve Bank. Bidvest, the logistics company, has also recently announced its plans to list its food business in London.

But perhaps the most invidious case is that of SASOL:

***

"SASOL sits pretty - what about SA?"

* SASOL was set up in 1950 as a state-owned entity * Subsidised for many years to cover the difference between the global price of oil (around $25) and SASOL's cost to produce oil from coal (around $40??) * Privatised from 1979, shares sold at discount to established white monopoly capital * Currently supplies about 35% of our petrol needs

* But global price of oil now around $90 -$100/barrel, and SASOL sells at the pump at import parity price - we are subsidising super-profits for SASOL

* In 2006 with global oil price around $60, Min of Finance established a Task Team to look at a windfall tax proposal * In 2007 the Task Team recommended a windfall tax * However, instead Treasury reached "gentleman's" agreement - in exchange for no windfall tax SASOL to invest in a new coal-to-oil plant in Limpopo (Mafutha)

* 2012 - global oil price $120, SASOL's net profit = R24bn - but still no Mafutha

* 2013 - SASOL announces R200bn investment in gas to liquid plant in...Louisiana, USA!!! Even neo-liberal conservatives in SA were outraged:

"Born courtesy of taxpayers...SA's biggest company and world leader in various critical energy technologies is investing ever more deeply in the US than it is here. This may be the right thing for the company, but is it right for the country?" (David Gleason, "SASOL sits pretty - what about SA?", Business Day, 4 July 2013).

***

This massive disinvestment out of SA is presented by business interests as a "vote of no confidence" in the present government. See for instance a recent The Times front page story "Big business votes with its feet" (October 6, 2014). The story tells us that:

"a great trek of companies from SA is under way, even as government talks of ‘re-industrialising' the economy. Multinational companies increasingly view their South African operations as ‘orphan assets', says Investment Solutions economist Chris Hart." - South African Chamber of Commerce and Industry policy analyst, Pietman Roos, is quoted later in the Story blaming the Zuma administration over the past five-and-a-half years:

"the high cost of doing business here and general unpredictability of policy changes are major reasons" for disinvestment.

There are several things in this pervasive perspective that require critical engagement:

* Most of these "multi-nationals" are actual (or former) South African companies that benefited from decades of support from white minority regimes, including the supply of cheap black labour.

The "vote of no confidence" is a vote of no confidence in a non-racial democracy that includes worker rights.

* The disinvestment trends started in the mid-1990s with Anglo, De Beers, Old Mutual, SAB Miller, Investec, Didata, Gencor, Liberty etc. being allowed to dual list overseas. This is not a process that has suddenly happened over the last five years.

* Part of the "cost-of-doing-business" complaint relates to electricity costs. As we have noted above, it is only since 1994 that Eskom has been given a major developmental mandate (providing 7 million electricity connections to poor households in 20 years, for instance, versus a mere 5 million household connections in the entire previous century). This is one (admittedly not the only) reason for an increased electricity tariff for business.

* Particularly in the case of the mining houses, the restructuring of their mining interests in SA often relates to the approaching exhaustion of mines that have been intensively exploited over several decades. Again, these moves often have very little to do with "policy uncertainty", or the cost of labour.

* It is important to understand that these processes of re-location and financialisation are global trends, and not specific SA phenomena.

Monopoly capital constantly seeks to use its power and mobility to leverage ever more policy concessions out of government - it bullied the Mandela administration, it bullied the Mbeki administration, just as it seeks to bully the Zuma administration with dire threats of disinvestment, and complaints about policy uncertainty.

Connecting all of this to the earlier analysis of SA's underlying systemic crises we can see that (former) South African monopoly capital is increasingly solving its own semi-peripheralisation within the global imperialist value chain by becoming global itself. This involves a relative (and in some cases complete) de-linking from SA. It might be good for monopoly capital - but the massive disinvestment out of SA is the most active factor in deepening South Africa's triple crisis of unemployment, poverty and inequality.

This massive outflow of capital is also directly responsible for SA's foreign debt rising from $25bn in 1994 to $140bn today. It is a ratio to GDP that is as high as the mid-1980s apartheid-era debt crisis. Our foreign debt ratio creates further dependencies on speculative investment from abroad, and increasing exposure to the verdict of ratings agencies and "investor sentiment".

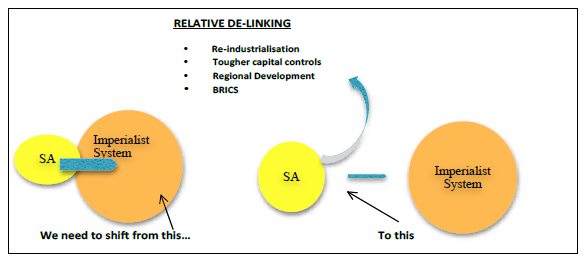

What is to be done? In what follows we will argue that any counter-offensive requires using state power and popular power to effect, in turn, a RELATIVE DE-LINKING of our society from the globally dominant imperialist political economy. We say "relative" - because there is no immediate or medium-term prospect for a complete rupture.

We are now in a better position to give more meaningful content to the concept of a National Democratic Revolution in its second phase. The "national democratic" in NDR refers to three critical and inter-related dimensions:

* The struggle for a democratic non-racial society - overcoming the terrible legacy of racial oppression, and the persistence of racism in our society (not least in the work-place);

* The struggle for nation building - and in particular the struggle to forge the socio-economic material conditions for national unity - which means the transformation of the "internal colonial", core/periphery features of our society that still persist;

* The struggle for democratic national sovereignty - in other words the struggle to overcome SA's semi-peripheral economic subordination within the global economy, in the process defending, for instance, our democratic electoral mandate in the face of monopoly capital's persistent attempts to dictate different policies.

The first dimension is the one that occupied prime place within the first phase - the de-racialisation of our society. As we have noted already, this was largely attempted in the first phase through addressing the legitimate national grievances of the black majority (Africans in particular, blacks in general). In the first phase, the approach to this imperative focused on extending and consolidating equal rights to all (regardless of race) and of applying a range of positive discriminatory redress measures for those historically disadvantaged. This aspect of the struggle remains a critical pillar of the NDR.

However, as we have already indicated, because emphasis on this dimension tended to be insufficiently complemented by other dimensions of the "national question", many of the systemic underpinnings of national/racial oppression of the majority have remained stubbornly in place. Despite extensive redress measures, the triple crises of unemployment, poverty and inequality remain strongly inflected by race. That is why it is essential to more forcefully highlight two other critical dimensions of the "national question" - the "external" and the "internal" dimensions historically associated with CST.

The external CST dimension - the ongoing struggle for democratic national sovereignty

This is a struggle to ensure that a national democratic popular mandate and its key developmental objectives are not continuously usurped and undermined by external (imperialist or trans-nationalised ex-SA monopoly capital) interests and their local comprador (fronting) allies. This relates to a struggle to overcome SA's semi-peripheral economic position within the global capitalist system - in other words, to transform the "external" core-periphery relation. A range of interventions are required:

Most important is the re-industrialisation of our economy so that we move up the global productive value chain. It is notable that the three key spurts of industrialisation within our economy occurred at times when there was a relative de-linking from the imperialist north - during the two World Wars (1914-18 and 1939-1945), and, paradoxically, in the late-70s into the 80s when international sanctions (together with prescribed asset legislation and tough exchange controls) compelled the dominant South African mineral-energy-finance complex to deploy surplus into domestic diversification in manufacturing, forestry, logistics and retail.

It must be added that these period of relative de-linking (notably the first two) were accompanied in the 1930s and 1960s with the determined use by the respective minority regimes of a range of state interventionist measures into the economy - extensive development of SOEs, industrial policy measures, skilling initiatives (using SOEs and directed at white artisanal training), prescribed assets, the development of coops, agricultural marketing boards, trade protectionism, etc. The monopoly sector has used the post-1994 "normalisation" of SA's international relations to reverse domestic diversification and investment.

Post-1994 we have seen a major process of de-industrialisation as capital surplus has been expatriated through divestment from horizontal linkages within SA, with an emphasis on "maximising" of global share-holder value, and accelerated financialisation and transnationalisation by major South African monopolies (Anglo, Old Mutual, SAB, SASOL, etc.). Illegal capital flight, dual listings, foreign entry into our economy (Walmart), the misguided relaxation of exchange controls, and our inordinate reliance on short-term speculative flows have all played a part in deepening SA's subordination within the global capitalist accumulation process. A critical component of the second phase is to roll-back what has been a hugely problematic reversal since the early 1990s.

If "relative de-linking" from the imperialist north was a key factor in earlier spurts of industrialisation what factors are there in the present that could be leveraged for a relative de-linking now? Increased global multi-polarity is an important factor - and this is the context in which BRICS, for instance, needs to be viewed. Even more important for SA are the possibilities of regional development - an African agenda that must, in turn, break with the old-apartheid era, neo-colonial, sub-imperialist relationship between SA and its region. We now require (for SA's own sovereign advance) a balanced, region-wide process of development and industrialisation.

This in turn needs to be supported by infrastructure development that begins to break with a largely persisting (neo-)colonial pattern of logistical infrastructure premised on natural resource extraction from our region to the imperial north - pit-to-port and plantation-to-port rail lines, for instance, or energy and water supply infrastructure still monopolised by mines and large corporate agriculture.

The balanced development and industrialisation of our region requires a different pattern of infrastructure (including logistics, water, energy, and IT). The critical PICC SIP 17 (the North- South corridor), which has failed to be consolidated in the past three years, becomes especially important in this context.

Our trade, diplomatic and even military/peace-keeping strategic interventions all need to be guided by these developmental priorities.

Transforming our skewed internal development - placing our society onto a new growth and developmental path

Because of their systemic inter-linkages, addressing the "internal" CST legacy is, of course, closely linked to the struggle for national sovereignty, and many of the same programmatic priorities are required.

It is important to underline that the policy fundamentals for these programmatic priorities to place our society onto a new growth and development path are already basically in place, and they include:

The New Growth Path whose core focus is to place our productive economy onto an employmentcreating trajectory. The NGP identifies 13 jobs and growth drivers: Infrastructure build; mining and beneficiation; manufacturing; tourism; greening the economy; rural development; the Industrial Policy Action Plan; agriculture and agro-processing; the knowledge economy; the social economy; the public sector; education and training; and African regional development.

The Industrial Policy Action Plan (IPAP) is a key pillar the NGP. This is a re-iterative state-led action plan continuously updated and focused on Re-industrialisation. Beneficiation of our mineral resources is a key pillar of IPAP, building on the platform of what remains SA's relative competitive advantage. Agro-processing, localisation and state procurement policies are other key points of leverage for driving local manufacturing jobs.

The National Infrastructure Plan co-ordinated through the Presidential Infrastructure Coordinating Commission (PICC) through 18 over-arching Strategic Integrated Plans (SIPs). Amongst other things the NIP seeks to support the re-industrialisation programme by:

Facilitating beneficiation and breaking with the excessive pit-to-port, export configuration of our logistics system by ensuring better logistical connectivity to local upstream and downstream manufacturing;

Further supporting the re-industrialisation programme by ensuring that key manufactured inputs for infrastructure are locally manufactured; and

The NIP is also focused upon using the infrastructure build programme to radically transform the core-periphery pattern of development / under-development hard-wired into the "internal" dimension of CST. This latter critically involves transformative urban development (new human settlement patterns, public transport, etc.); and the transformation of under-development in rural areas.

Other important strategic interventions to place our economy on to a new growth and development path include:

* the ANC's State Intervention in the Mining Sector (SIMS) policy;

* interventions to break the collusive conduct and market power of private monopoly capital - through a range of regulatory and other interventions, using the Competition Commission and related institutions;

* Transforming the financial sector - DFIs, industrial investment, prescribed assets, trade union investment funds and greater working class strategic control over retirement funds.

* Development of SMMEs and coops around the industrialisation process * Transforming the education and training system to align with and support our developmental and productive economy objectives * Changing our energy mix - greater self-reliance, greater sustainability * Linking BBBEE more effectively to our developmental and productive economy objectives - with an emphasis on fostering a productive entrepreneurship, including a new cadre of black industrialists.

As can be seen from the broad outline of key strategic interventions required to advance a decisive transition to a new growth and development path, the second radical phase of the NDR is not something we are just talking about. Many of its key elements are already under implementation.

What is required is a more decisive and more coherent effort.

There also needs to be a better aligned macro-economic policy package that supports all of the above programmatic priorities.

Ecological sustainability and the Second Radical Phase

SA's environment has been gravely damaged by the legacy of CST and its economic growth path:

* The centrality of MINING and mining monopoly has resulted in huge damage to environments and to the health of miners and mining communities. Acid Mine Drainage is now a major threat to significant parts of Gauteng. Un-rehabilitated mine dumps and abandoned mines are monuments to the ecological irresponsibility of the mining corporations that have extracted non-renewable wealth out of our country and then walked away.

* SA's abundant cheap coal-resources locked us into an ENERGY-INTENSIVE growth path with amongst the highest per capita carbon emissions in the world. Both Eskom and SASOL are major polluters - SA contributes 50% of the entire African continent's CO2 emissions. The cheap energy produced from coal-fired power stations (until recently) also led to perverse "industrial policy" incentives - like the post-1994 20-year contracts with BHP aluminium smelters in Richards Bay in which electricity was guaranteed at bargain rates. SA doesn't mine bauxite (the mineral used for the production of aluminium). The two Richards Bay smelters have provided cheap electricity to BHP, plugging into our grid, and consuming the equivalent amount of electricity that could electrify a medium sized city.

* The second historical pillar of SA's economy - AGRICULTURE - has also had a major negative ecological impact. Racially-skewed land ownership and, over the past decades, the rapid monopoly concentration of production with increasing capitalisation has led, not only to job losses, but also to excessive use of pesticides, herbicides, fertilisers, as well GM crops with negative environmental impacts. Large commercial mono-crop farming has displaced more ecologically sustainable mixedcrop medium scale farming.

* The SPATIAL features (core-periphery) intrinsically linked into our CST legacy also have many damaging ecological features:

Over-crowding in the labour-reserves (the ex-bantustans) has resulted in major degradation of soils, and serious erosion

Townships and informal settlements are often located down-wind of mine-dumps, or downstream of chemical plants, or in precarious ecological environments prone to flooding, for instance. Climate change is likely to have an increased impact on the resilience of most working-class communities

By contrast, private property speculation has driven skewed urbanisation for the middle strata - suburban development, favouring car-dependent, "green belt" sprawling settlements. Apart from traffic related pollution, this suburban development has displaced small-scale farming and marketgarden production. Scarce water resources are consumed in swimming pools and golf courses.

* On a REGIONAL scale, the historical centrality of mining in SA's economy has resulted in massive economic and population growth in our Gauteng economic hub. Local water resources are inadequate to sustain Gauteng's current growth trajectory. Gauteng is reliant on water from the Lesotho Highlands Water Scheme. There is now a race against time to complete the second phase of this scheme, while at the same time dealing with Acid Mine Drainage which is currently being dealt with by diluting AMD with clean water - a massive waste of a valuable and scarce resource.

These and other major ecological sustainability challenges in SA present us with a serious dilemma as we advance a second radical phase of the NDR. A central pillar of our job creation priority is re-industrialisation leveraged off our abundant mineral resources. However, beneficiation is ENERGY INTENSIVE and in the foreseeable future the principal source of base-load electricity will have to come from coal-fired power stations. Apart from nuclear energy, the other renewable sources available to us (solar and wind), while their costs are becoming comparable to coal, are simply not able to provide reliable base-load to support industrialisation.

This does not mean that we should be dismissive of the imperative of placing SA onto an ecologically sustainable development path. This will require effective, state-led planning with clear long-range understanding of trade-offs and risks. Also required is a serious state capacity to regulate land-use and water-use and the exploitation of natural resources. Left to anarchic market forces the irreversible destruction of our environment will continue. A key emphasis of the second phase of the NDR must be to ensure greater environmental justice and resilience for urban and rural working class communities.

Relative de-linking on the internal front - Changing the balance of forces, or how to leverage a relative de-linking of popular strata from the depradations of the capitalist market.

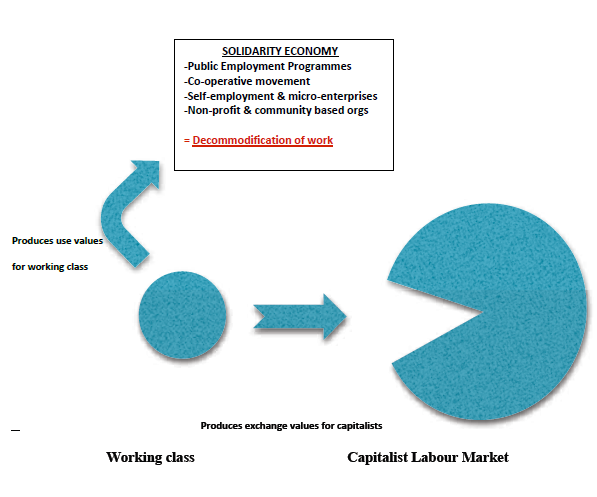

In earlier sections of this intervention we briefly sketched out how colonial dispossession and apartheid social-engineering squeezed millions of South Africans out of productive, homestead-based communal work and into coerced employment for someone else's profit. For those living in former bantustans, or in urban townships and informal settlements, the prospects of a sustainable livelihood still rest considerably on the chance of employment, that is, selling their labour power on a capitalist market.

But the core crisis of our society is precisely that there are many more proletarianised sellers than capitalist buyers. This, in turn, reproduces a highly skewed class balance of forces - in which millions of South Africans have no alternative livelihood, and are forced into employment on unfavourable terms as low paid temporary workers, as labour brokered casuals, etc. This "precariat", this huge reserve army of labour further weakens the negotiating leverage of the formally employed working class.

This is why a wide range of initiatives, including the many redistributive initiatives noted earlier (social grants, social housing, non-fee schooling, access to health-care, the roll-out of subsidized public transport and the progressive de-commodification of at least basic amounts of water and electricity) should all be understood not just as "poverty alleviation", but as state-led interventions that potentially help to alter the class balance of forces by partially de-linking the livelihoods of the popular strata from naked dependency on the capitalist market.

Moreover, the more we strengthen these social wage interventions the less pressure is placed on the wage of the formally employed. COSATU is not incorrect when it argues that perhaps the greatest redistribution in SA is the redistribution of wages of the formally employed among extended families and other dependents in both urban and rural areas. This puts huge pressure on wage negotiations and is a factor in re-producing a stratified labour market with pockets of relatively well-paid workers where for one or another reason trade union organization is effective.

However, state-led redistributive measures, while potentially creating greater popular capacity, do not in themselves transform the productive economy.

It is important to make stronger links between existing redistributive measures and the transformation of production itself, amongst other things, in regard to:

Land reform - it is imperative that land reform is much more closely linked into a sustainable productive perspective. This involves linking land reform much more actively into the wider objective of achieving greater food security and food sovereignty - focusing on breaking the market domination of agricultural, agro-processing and food retail monopolies (which are increasingly financialised and transnationalised) - through more effective regulation, through re-building public sector support to farming, especially medium and small-scale mixed farming (through research, veterinary services, market support, localised storage and processing facilities, appropriate infrastructure, etc.).

It is critical to align land reform programmes to a sustainable productive perspective, and to address the democratisation of communal land tenure through the implementation of Communal Property Associations. Urban and rural household and community food gardens are also an important component of ensuring food security and sovereignty.

The productive economy needs also to be progressively transformed through the transformation of the work-place, to move increasingly towards the democratization of the work-place. Key priorities are addressing the still highly racialized nature of most private sector work-places, as well as gender discrimination.

Public Employment Programmes - and the De-Commodification of Work

In response to SA's unemployment and poverty crisis, we have developed an internationally innovative array of public employment programmes - grouped under the broad umbrella of the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP). In the past 10 years over 6-million work opportunities have been provided in a wide range of sectors - infrastructure, the social and culture sectors, environment, and the community work programme. Many of these public employment programmes also work closely with non-profit and community-based formations. While these programmes differ in varying ways they all involve at least three dimensions:

* Through a minimum wage (or "stipend") they provide some basic income relief to poor households, and can be seen as a component of the social security net that we are endeavouring to broaden;

* They provide work experience in a context where millions of South Africans have little or no experience of collective work. The work experience also comes with training - varying from fairly basic skills in the case of CWP, for instance, through to a high-level of training, in the Working on Fire programme, for instance. The intention is to restore some level of dignity to the unemployed;

and

* Through these programmes, public assets are created or maintained (social infrastructure, rural roads, etc.), and services are provided (home-based care, ECD care, homework supervision, cleaning of parks, food gardens and school feeding, etc.). In some cases, the services provided make a major economic contribution. In the case of Working for Water as much as R400bn worth of water has been saved and 71% of grazing land rescued.

Perhaps most importantly, these public employment programmes potentially provide a relative de-linking of poor communities from the depredations of the capitalist labour market. Through community productive work they enhance community coherence, build collective resilience, foster a sense of collective responsibility for and ownership of local resources and amenities, and help to forge a different relationship between the state and popular strata. In short, they have the potential to help transform both the state and popular communities - breaking with the idea of a "top-down delivery state" servicing (often resentful) "customer citizens". The public employment programmes create a terrain on which popular strata can once more become active protagonists (motive forces) in their own development.

***

Forging a different countryside - Siyakholwa in Keiskammahoek

* Siyakholwa Foundation was formed in 2007 as a non-profit organization. It was based in an old saw-mill in the village of Qobaqoba in Keiskammahoek. The original intention was to foster farming co-ops in this impoverished area of the Eastern Cape

* After trials-and-errors with the co-ops - including a bumper cabbage crop for which they could not find a market - Siyakholwa linked up with government's Community Work Programme.

* COGTA, through the CWP programme, provides a stipend for 1,500 participants working in 37 surrounding villages. In each of the 37 villages there is a Village Committee that selects participants for the programme and collectively identifies public work in the village. This includes identifying house-holds in distress requiring home-based care; food gardens in schools and creches which also supply free meals to students; the maintenance of public facilities in the village (school buildings, the grave-yard, etc.).

* Each of the 1,500 participants works 8-days a month on community work, leaving other time to work in their own fields or do other things. The monthly stipend earned (around R500) provides some income relief to poor households - but, above all, the programme has helped to build community solidarity in the villages and a sense of social usefulness and pride among the participants.

* Siyakholwa, the non-profit organization, acts as a local implementing agent for the programme.

It operates in the renovated sheds of the old saw-mill. The centre provides training and resourcing for the village food-gardens (soil conservation, composting, seeds); and other skills training - including welding, basic auto-repairs, bee-keeping, and computer literacy. In the grounds of the centre is an orchard with 1000 peach trees (providing cheap fruit to local villages and a supply of fruit for a team of women trained in jam making); a distillery to produce essential oils from rose geranium plants that grow very easily in the area with cuttings provided free to growers in the villages; and experimental food gardens, vermiculture, etc. One of the aims is to train two basic handy-men for all 37 villages. Siyakholwa training is funded partly through COGTA's CWP budget, but other sources (private and public) are also tapped into.

* Because of its success, Siyakholwa, working with provincial government structures, is now helping to establish similar programmes in other districts of the Eastern Cape.

***

While the Siyakholwa Keiskammahoek project is among the more exemplary of the public employment projects in SA, there are tens of thousands of others in both rural and urban settings. We need to make better connections between our public employment programmes and a range of other popular initiatives - including cooperative development, micro-enterprises, street trading and other selfemployment activities, and a wide range of non-profit and community based organisations and volunteerism.

All of these require relative degrees of sheltering from the depredations of the capitalist commodity market, and all are focused primarily on securing livelihoods for their participants rather than ever-expanding surplus and profits through the exploitation of other people's labour.

Their principal "capital" is, in fact, their own individual and collective labour. In progressive circles in Latin America and Europe there are movements aimed at supporting, networking and advancing this potentially non-capitalist sector variously described as a "solidarity", "co-operative" or "social" economy.

In SA we need, as ONE component of the second radical phase of the NDR, to consolidate a relative de-linking of the poor, the un- and under-employed through consolidating a solidarity economy so that livelihoods are not entirely dependent on finding willing capitalist buyers of labour-power. In other words, this is the second relative de-linking that we need to foster as part of the second radical phase of the NDR.

THE STRUGGLE FOR GENDER EQUALITY

The struggle for Gender Equality and the Second Radical Phase of the NDR

The struggle for substantive gender equality and the rolling back of the legacy of entrenched patriarchy are intrinsically connected to the major arguments developed throughout this intervention.

Since 1994 we have seen constitutional and legal entrenchment of gender rights. In line with other achievements of the first phase, there have been important if uneven gains made in ensuring greater gender representivity in parliament, the judiciary and senior civil service, for instance. However, all socio-economic indicators relating to the triple crisis of unemployment, poverty and inequality indicate that women (and particularly black women in rural areas and in informal settlements) continue to suffer the brunt of the crisis and its related impacts.

Friedrich Engels perceptively attributed gender discrimination to the development of a gendered division of labour in which women became responsible for less valued "reproductive" work, while men monopolised more valued "productive" work. Capitalism has deepened the discrimination by regarding much "reproductive" work, or non-market based work as "not real work".

While patriarchy remains a factor in most societies, SA's CST history has imparted a particularly problematic form of patriarchy. This is directly related to the use and perversion of "traditional" patriarchal authority ("traditional leadership") in the labour reserves (the ex-Bantustans) as a critical cornerstone of the internal dimension of CST. Rural women (and children - herd-boys, makoti, etc) bore the brunt of reproducing "cheap" male migrant labour for the mines. Still today women are in the majority in the former bantustans and they continue often to be subjected to harsh patriarchal tribal authority and backward customs - suffering discrimination, for instance, in terms of the allocation of more productive land and resources.

The legacy of CST and male migrant labour is reflected in many contemporary statistics. For instance the percentage of African married women living apart from their partners is over 25% compared to other groups where the figure is 10% or less. For rural women (the majority being African) married women living apart from partners rises to 35%.

The impact of this in terms of household livelihoods is dramatic. Female-headed households are more likely to have insufficient food (21%) than male-headed households (15,8%), and are more likely to run out of money to buy food (27,2%) compared to 19,3%. (Stats SA General Household Survey 2012). This gendered vulnerability to hunger is, in turn, related:

* To higher levels of unemployment among women (in 2011, in the narrow definition, female unemployment was 27,6% compared to male unemployment of 22,2%); and

* To the fact that, when in employment, women are typically paid less, or are active in lower-paid jobs.

This is reflected in marked gender differences in economic activity. Of the economically active in SA, 69% of males and only 55% of females were involved in "market only" activities. By contrast, 37,8% of economically active females were involved only in non-market activities (compared to 25% of males). Stats SA defines "non-market economic activity" as work in which "goods are produced for consumption within the household and for which there is no payment". It is mainly subsistence farming that is counted in this category. Stats SA does not include "housework or care for older people or children" "as these are not considered ‘economic activities'".

In addressing gender-based oppression we must, of course, not be narrowly economistic. Other discriminatory practices, social norms and stereotypes all play a role in perpetuating gendered oppression. However, as we have argued throughout this discussion document, getting to the roots of the problem requires active transformation of the productive economy and, indeed, an interrogation of what we understand and value as "productive". A second radical phase of the NDR requires the radical transformation of the root causes of the triple (class, race and gendered) oppression of the majority of South African women.

The Battle of Ideas

The strategic perspective of a second radical phase of the NDR sketched out in broad brush-strokes in this intervention is, of course, not the only strategic "narrative" at play in SA at present. In fact, because we have not given sufficient context and content to the idea of a second radical phase - other narratives often enjoy greater prominence and credibility in public discourse and debate. Part of advancing and defending a second radical phase will, therefore, necessarily involve actively engaging in the battle of ideas and developing a clearer perspective of the main features and weaknesses of competing "narratives".

Growth-then-redistribution

The dominant "narrative" remains the basically neo-liberal notion that SA's socio-economic challenges can only (and will only) be solved through capitalist-driven growth that will "grow the cake" - providing greater resources for redistribution to address the problems of poverty and inequality. See for instance the DA's web-site statement: "if we are to open up opportunities for all and create a prosperous, inclusive society, the pie needs to get bigger so there is more to share." While the growth-then-redistribution narrative might acknowledge some structural challenges in SA's political economy (for example, a skills deficit, or energy challenges), it fails to go to the root of the problem. It essentially seeks to put SA back into the same "growth path" which, as this intervention has sought to illustrate, is precisely what is at the root of the reproduction of our triple crisis. For this reason, the growth-then-redistribution narrative dismisses the need for a RADICAL transformation of our productive economy, preferring, instead, to leave growth to the "market".

The growth-then-redistribution narrative is further based on two flawed assumptions:

* In trumpeting growth as the cure to our problems it is essentially evoking "growth" as measured by the problematic "GDP" metric - but what actually is GDP measuring?

* For the growth-then-redistribution narrative the means to achieving its objective of "growth" is typically a social compact between government, business and labour, an "economic CODESA".

Let's briefly consider each of these flawed positions in turn:

The GDP myth

Internationally, and not just from left quarters, the socio-economic relevance of the GDP metric has been increasingly questioned. In 2008 Nicolas Sarkozky's centre-right French government, for instance, appointed two economics Nobel laureates, Joseph Stiglitz and Amartya Sen to head a commission to examine the appropriateness of GDP in assessing economic performance and social progress.1 Their report begins with the pertinent observation that "what we measure shapes what we collectively strive to pursue - and what we pursue determines what we measure." (p.10) The authors then organise what they call "the case against GDP" into seven basic areas:

1. Distribution - GDP does not tell us how growth is distributed at the household level. The example they cite is the US where GDP has more than doubled over the past 30 years, while median household income grew only 16 percent.

2. Quantity versus quality - GDP measures the quantity of traded goods and services, but not the quality. Money spent on gambling is just as "good" as money spent on books. Traffic congestion contributes to GDP by increasing the sale of petrol.

3. Defensive expenditures - GDP does not distinguish between expenditure that positively increases human welfare (education, for instance), and "defensive expenditure" such as cleaning up industrial disasters or military spending.

4. Real economic value versus borrowed and speculative gains - GDP tells us nothing about the sustainability of economic activity. Financial services add to GDP regardless of whether they are allocating capital to productive investment or fuelling gigantic asset bubbles with speculation.

5. The depletion of natural resources and ecosystem services - GDP ignores environmental problems. Economic activity that depletes natural resources (mining in South Africa) is just as valuable, by GDP standards, as economic activity using natural resources sustainably.

6. Non-market activities - GDP tells us nothing about the value generated by non-market activities - in the household, in the public sector, in civil society, and in the broader ecological systems.

In Third World countries, the authors note, this is a particular problem since much activity takes place in the "informal" economy.

7. Social well-being - GDP mostly does not track indicators of social well-being like rates of poverty, literacy, or life-expectancy.

There are many other similar critiques of the GDP metric2. Yet, GDP still remains the Holy Grail in most mainstream commentary when assessing how SA is doing, and what needs to change in order to achieve "higher levels of growth". Clearly powerful interests are vested in the preservation of this highly distorting means of assessing the well-being of our economy and society.

The "economic CODESA" myth

The growth-then-redistribution supporters in SA often recommend a "social compact", or an "economic CODESA" as the way out of our current predicament. Essentially what they have in mind is a deal between business, labour and government "to get growth moving". Labour agrees to keep wage increases below productivity gains; business agrees to plough back into SA the increased surplus in job creating investments; and government uses increasing fiscal revenues to:

* First lower the cost to doing business for business (by investing in logistical and energy infrastructure, for instance); and

* Secondly, lower the cost of living for workers by way of social wage expansion (provision of social housing, public transport, etc.).

In the course of this intervention we have noted that, in fact, labour productivity has increased significantly since 1994 in SA, largely as a result of growing capital intensity and the shedding of large numbers of semi- and unskilled jobs, while capital's share of surplus has grown. However, the increased surplus has NOT, generally, been invested back into job-creating production in SA. The equivalent of some 20-25% of GDP since 1994 has been expatriated by way dual listings, dividend payments, tax avoidance, transfer pricing, foreign buy-outs, and illegal capital flight.3 This draining of capital and the resulting limitation of fiscal resources will dangerously expose a "redistributive" government in any putative social compact. The sheer scale of reproduced poverty, inequality and unemployment, and the limited fiscal resources to roll out social wage measures will inevitably set up for failure a largely redistributive government that stays clear of transforming the productive economy.

While wholesale trans-nationalisation and financialisation are related in part to the many specific features of South African monopoly capital, it is important to appreciate that they are also global capitalist trends. The belief that a social compact, an "economic CODESA", will open the way to sustained growth and redistribution in SA rests on the illusion that monopoly capital is still operating in the period 1945-1973 when, in much of the DEVELOPED capitalist world, explicit or implicit national social accords drove post-war reconstruction, resulting in rising living standards for workers and sustained growth.

National bourgeoisies in much of war-torn Western Europe, for instance, contributed out of self-interest, by way of high taxation and productive investment, to the patriotic effort of reconstruction and development. However, from around 1973, with West European and Japanese national capitals now recovered, and with near full employment within their economies and thus a considerably strengthened working class, along with new sets of problems (inflation, growth slow-down) - European and Japanese capital increasingly sought ways of escaping their respective national compacts and their accompanying "patriotic" responsibilities, by moving their investments to lower-wage and lower-tax destinations.

The switch from neo-Keynesianism to neo-liberalism as the hegemonic imperialist ideology from the late-1970s through to the present is directly linked to these developments. Under the aegis of Thatcherism, Reaganomics, and other variants of neo-liberalism, advances towards social equality in the developed capitalist core have been dramatically reversed as have trade union gains. The 1945- 1973 "golden age" of capitalism in the developed capitalist core (Western Europe, US and Japan) has proven to be a relatively brief historical interlude and one that was largely confined to the geo-political "North".

The South African advocates of a grand "social contract" between business, labour and government as the key solution to our socio-economic crises are confused about both our place and our time.

They misunderstand both our geo-political location (as a semi-peripheral capitalist economy in the "South"), and the current historical conjuncture in capitalism's development (accelerated globalisation, financialisation, and the domination of the casino economy). This is not to say that we should never engage capital whether as government, trade unions, or social movements. We should certainly bring state, working class and popular power to bear on the (diverse) sectors and strata of capital. Through sustained struggle there will be opportunities to leverage agreements and sectoral advances. But the idea that there is a realistic possibility of a grand, all-in, 20- or 30-year social compact with monopoly capital, a deal in which increased investment is made in response to wage restraint, is simply utopian.

Our experience over the past 20 years has demonstrated this quite clearly and brutally.

Nevertheless the illusion persists, including within parts of our own movement.

A recent example is provided by cde Joel Netshitenzhe who sought to give his own meaning to the idea of a second "radical" phase. Concluding a longish Mail & Guardian intervention (" ‘Radical' change is our collective responsibility", 27 June, 2014) he argues that SA's challenges require that "all societal leaders seriously work towards a social compact of common interests...there are historical moments when it is truly ‘radical' to rise above the false comfort of ideological fundamentalisms."

There are four inter-related things (which we have underlined here) to be noted in this, the concluding passage in cde Netshitenzhe's article:

* It is an appeal to "leaders" - rather than (or rather than also) a narrative of mobilising popular forces as key protagonists of transformation;

* It is an appeal to "all" leaders to work towards a "social compact of common interests" - that is, it is essentially a vision of elite pacting;

* It asserts that the discovery of overarching "common interests" requires that leaders "rise above the false comfort of ideological fundamentalism". While clearly we should not be stuck within dogmatic fundamentalism, the argument here can easily lead to a mistaken belief that social conflict and contradiction are purely the result of subjective intransigence, of ideological tunnelvision, of a "communication failure". This, in turn, can lead to the illusion of an "ideology-free", "end-of-history", "purely technical" consensus that will solve our socio-economic crises; and

* The intervention consistently places the word "radical" in inverted commas - cde Netshitenzhe knows very well he is simply paying lip-service to the word.4 Cde Netshitenzhe is, of course, not alone. It is a perspective shared with others of a centre-left, social-liberal persuasion. The generally acute commentator, Steven Friedman, is also a consistent proponent of an overarching social pact.5