George Palmer died in Palm Springs on New Year's Day at the age of 92

I joined the Financial Mail (FM) in January 1973 and worked there for more than six years. The editor, George Palmer, had a formidable reputation both as an intellectual and as an editor. He was also a liberal. He had no truck with notions that a financial paper should stick to business and economics and avoid politics, though many people thought that. There were of course quite a lot of conservative writers on the FM, and some of them thought the paper had become too "political".

Palmer sometimes toned down some of my articles, but otherwise he allowed me as much freedom as I could reasonably have wished for – although on one occasion at an editorial meeting when I suggested yet another political leader, he thumped his desk and declared "I want stories about making money!"

Shortly after joining the FM I wrote an article that caused the Palabora Mining Company, a subsidiary of the global giant RTZ, to seek an urgent interdict against us. Before they abandoned it I had run up a large bill for the publication consulting various lawyers. A couple of days later some of the company's executives called on Palmer. I thought I was for the high jump. But Palmer promoted me and put my wages up from R350 to R500 a month.

On another occasion I accompanied him to see a top General Mining man who was objecting to something we were planning to write about migratory labour. We listened politely to a torrent of abuse over lunch, after which Palmer told me to just go ahead and write the article, which was even more critical than the one to which the mining man had been objecting.

On another occasion I accompanied him to see a top General Mining man who was objecting to something we were planning to write about migratory labour. We listened politely to a torrent of abuse over lunch, after which Palmer told me to just go ahead and write the article, which was even more critical than the one to which the mining man had been objecting.

Palmer also once defied his chairman when the latter instructed him to spike an article to which a cabinet minister had objected. Palmer agreed, called us all in, and told us that if we wished to resign in protest he wouldn't hold it against us. However, we said, that would look like a protest against you. Rather go ahead and publish, and if he fires you we will then resign in solidarity with you. After a long discussion the matter was put to the vote and most of the 15 journalists present favoured going ahead with the article.

The chairman had threatened to stop the printing press to keep the FM off the street, but before he went home that night Palmer told us we had his authority to do whatever was necessary to make sure the paper appeared the next day. We made arrangements with the printing union to take instructions from no one but the editor's representative; if anyone else tried to enter the shop, the union would lock them out. The article duly appeared, and we all kept our jobs. We were all proud to be working for Palmer, and the atmosphere on the FM was as intellectually stimulating as Oxford tutorials. I was permitted also to accept speaking invitations around the country.

The FM was widely read not only in business but also in government. We knew also that it was one of the few papers political prisoners were allowed to read, although apparently Jackie Bosman's striking and often provocative covers were sometimes torn off. Under Palmer and his right-hand man and senior assistant editor, Graham Hatton, it was a uniquely powerful platform for liberal ideas.

Moreover, as a weekly it gave you time to research your articles more thoroughly than did a daily newspaper with its tighter deadline pressures. This meant that although the FM never hesitated in expressing forthright opinions, it was able to back them with plenty of hard factual data. "Seek truth from facts" applied as much there as it did at the South African Institute of Race Relations, which I later joined.

My time at the FM in the 1970s gave me the chance to chronicle the National Party's attempts to reconcile the irreconcilable – economic necessity and political ideology. The NP was simultaneously trying both to loosen and to strengthen apartheid policies. It was also trying to shift the basis of discrimination from race to nationality. We were relentless in exposing each twist and turn of this saga, both the absurdity and the inhumanity.

By the end of the 1970s Prime Minister John Vorster had been destroyed by what was usually known as "Muldergate" or the "Information scandal", when various newspapers exposed his government's secret funding of The Citizen newspaper using public money. "Muldergate" – named after the minister of information, Connie Mulder – was a forlorn attempt to counter the terrible image South Africa earned abroad for its apartheid policies.

Did the FM contribute to that poor image? The government certainly thought so. The secretary for information, Eschel Rhoodie, said that many of the most twisted and poisonous reports on South Africa overseas were based on reports from our own press, 70% from the Rand Daily Mail (RDM) and 20% from the FM. Since the RDM published six times a week and ourselves only once, this was quite a compliment to our influence.

The single most important reform of the 1970s was the granting to African workers of the same statutory trade union rights as had long been enjoyed by white, coloured, and Indian/Asian workers. The FM did more than any other paper to argue the case for statutory recognition of African unions. Not only did we repeatedly call for this, we were also the first paper to support the emerging independent African trade union movement. We did not let up on African union rights. In the first place we urged the government to grant them. But secondly we urged employers to take the initiative and negotiate with African unions. Though the government might frown on this, it was not actually illegal. We hammered this point at every opportunity.

The statutory recognition of African unions came into effect in October 1979. This was the most important victory so far against South Africa's racial legislation. It was won first and foremost by the courage and determination of the unions themselves. But of those who supported their struggle throughout the 1970s the FM was the most influential. Not only did we encourage them with powerful moral support and generally favourable publicity, but we helped to soften up both business and government opinion for what we knew Nic Wiehahn's commission on labour policy would recommend.

Despite all the difficulties African unions faced in the 1970s, their battle for recognition was essentially non-violent. It's a bitter irony that many present-day unions, enjoying statutory rights, so frequently use murderous violence to enforce compliance with strikes.

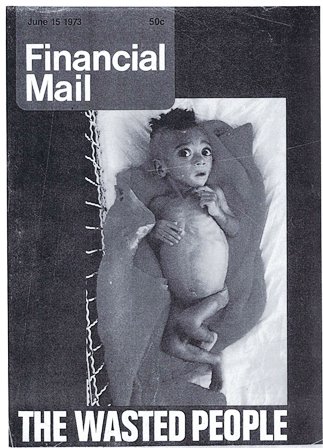

I was also allowed to write plenty of articles on the pass laws, forced removals, and numerous other aspects of apartheid. My first article on forced removals followed a visit to the Charles Johnson Memorial Hospital at Nqutu, some 80 kilometres from Dundee in what is now KwaZulu-Natal. The hospital was full of malnourished babies.

My article described the various categories of people subject to forced removal and resettlement in the already overcrowded homelands. I also painted a picture of the conditions in which resettled people, having lost their previous sources of income, now lived in what later became known as "dumping grounds". And of course many babies ended up in cots at Charles Johnson.

My article described the various categories of people subject to forced removal and resettlement in the already overcrowded homelands. I also painted a picture of the conditions in which resettled people, having lost their previous sources of income, now lived in what later became known as "dumping grounds". And of course many babies ended up in cots at Charles Johnson.

On the cover of the FM we put a colour photograph by David Goldblatt of one of the children with wide staring eyes, distended tummy, and rib-cage clearly visible. Published in June 1973, the article – entitled "The Wasted People" – was designed to shock, and it did. It also prompted a letter from Piet Riekert, economic adviser to the prime minister. It said that in view of the FM's "wide national and international circulation" the cover picture was "irresponsible and most unpatriotic" in stirring up emotions. "I am sorry George," he admonished Palmer, "I do not like this approach at all".

Palmer asked me how we should respond. I said that if the government did not believe us we should take them to see for themselves. So Palmer, Hatton, and I went over to Pretoria to meet Riekert. He brought along Braam Raubenheimer, who, as deputy minister of Bantu development, was the man responsible for forced removals.

They seemed to be after some sort of retraction or apology, but we said we would take them to Charles Johnson and the resettlement camps there and elsewhere. It was agreed that the government and the FM would each appoint three people to a team to go on this field trip. We got our three together in a few days. I then spent about 18 months negotiating with Raubenheimer about where we could go. Then I received a note from his department informing me that a certain top official would chair our investigation. They also rejected the people I'd suggested accompany us to the various resettlement areas they knew.

The only persons allowed to accompany our team would be officials. We declined to accept these restrictions. And that was the end of it. We continued to publish exposés of forced removals. Riekert might have had the ear of – or been the voice of – John Vorster, but that that was not going to stop the FM.

Looking back on this chain of events, I realise how brave Palmer was. Articles of this kind must have offended not only the government but most people in business as well. I wrote them, but the ultimate responsibility was his. However, it was clear that if you stood your ground the government sometimes backtracked. The then government no doubt got its way half of the time not by legislating but by bullying. The present government is much the same.

A year after the Charles Johnson article we published another cover story on forced removals. This was about "The nowhere city". The plan was to move 48 000 Africans from the Albany district (in which Grahamstown is situated) 45 kilometres away to a place called Committees Drift on the Ciskei side of the Great Fish River in the Eastern Cape. Here, according to Piet Koornhof, at the time deputy Bantu administration minister, the government planned not only an industrial area but the "finest black city in Africa". Plans were at an advanced stage, so much so that "many Bantu have expressed their appreciation to the government".

A year after the Charles Johnson article we published another cover story on forced removals. This was about "The nowhere city". The plan was to move 48 000 Africans from the Albany district (in which Grahamstown is situated) 45 kilometres away to a place called Committees Drift on the Ciskei side of the Great Fish River in the Eastern Cape. Here, according to Piet Koornhof, at the time deputy Bantu administration minister, the government planned not only an industrial area but the "finest black city in Africa". Plans were at an advanced stage, so much so that "many Bantu have expressed their appreciation to the government".

With Father Edmonstone, a local Jesuit priest, as my guide, I went to Committees Drift to take a look. There we found "a dirt road, four goats, a barbed wire fence, and a police station on the right bank of the river (since evacuated in the floods)." We put a photograph of this bleakness on the front cover.

The article on Committees Drift brought a letter from a reader, praising us: "When a national journal of the calibre of the FM, whose chief concern is with business and finance, can at the same time show an example of so much concern with justice and decency as appears from your leader on The Nowhere City, it must surely be one of the most hopeful signs for the future of this unhappy land to appear in recent times".

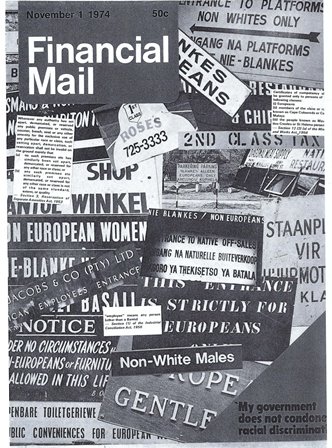

Pouring scorn on apartheid policies could sometimes be fun – never more so than when Pik Botha made his debut as South African ambassador to the United Nations in 1974. In a speech to the Security Council, he declared, "My government does not condone racial discrimination". This was too good an opportunity to miss.

I sent our photographer out to take photographs of some choice apartheid signs, such as one in a Doornfontein block of flats reading "UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES MAY NON-EUROPEANS OR FURNITURE BE ALLOWED IN THIS LIFT. BY ORDER". Juxtaposed with Pik's choice quote and supplemented by dozens of other photographs of signs and quotes from discriminatory laws, this made a wonderful front cover.

Inside I wrote, "Discrimination is at the very heart of our society. It governs every facet of our lives, from the cradle to the grave – and even beyond, since even our cemeteries are racially segregated. It is enforced where we live, where we work, where we play, where we learn, where we go when sick, and on the transport we use. Not only does government condone it; it systematically pursues it, preaches it, practices it, and enforces it. It is enshrined in our constitution, written into our laws, and enforced by our courts". I then went on to give chapter and verse.

I added that our ambassador's words would be "immortalised not because of noble sentiments or shining truth, but because they will surely rank among the most breathtaking falsifications ever presented to the world body". To this Palmer or whoever edited my article added, "unless they are followed by, and were intended to presage, some real action at home – and fast".

Even though this was intended to soften what I said, Vorster lashed out. Speaking in Zeerust and Bloemfontein, he said patriotism demanded that one should not write in this way because South Africa was fighting for her very existence. If editors carried on like this, the new press code the government had been discussing with the newspaper owners would not be worth the paper it was written on. Some of these editors appeared to be in rebellion against their directors. Nationalist sources were reported as saying that Vorster was waiting for just one newspaper to overstep the mark and he would proceed with legislation – already drafted – to curb the press. We carried on regardless.

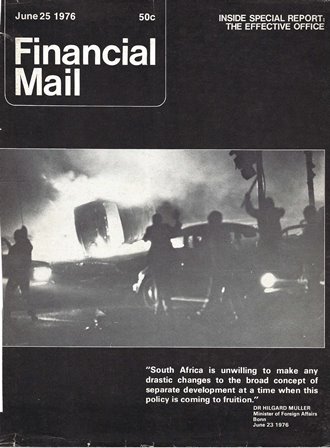

About 18 months after our exposé of Pik's Botha's promises, Soweto exploded when on 16th June 1976 police opened fire on schoolchildren marching in protest. We put a photograph of Soweto in flames on the front cover, along with a quote from the minister of foreign affairs, Hilgard Muller, speaking in Bonn only a week later: "South Africa is unwilling to make any drastic changes to the broad concept of separate development at a time when this policy is coming to fruition."

I'd handed in a tough leader, but Palmer put an even tougher introduction on top of it. Again quoting Muller's words, he wrote: "The fruits of the policy of apartheid are frustration, injustice, and hatred. Among its latest consequences are arson, rioting, and slaughter. If it is continued, the end result may well be revolution. It is a policy which is rejected by the broad mass of the African people. Yet they are being subjected to it with a remorseless insensitivity that can only invite disaster".

Re-reading some of what we wrote at the time makes me realise the extent to which the FM was not only engaged in a battle of ideas but also playing a leadership role in that battle. We were waging it on two fronts.

The first was business. Even though this was our biggest target market, we were highly critical of business for not taking a much bolder stance on political issues, especially those of black rights. And we did not hesitate to tell business what it should be doing. With a handful of well-known exceptions, business then was as timid as it is now. Indeed, it is something of a miracle that there is any support at all for the free-enterprise system among South African blacks. Not only was it largely closed to them except as customers and labourers, but business did little to try to persuade the government to open it up.

Such criticisms of apartheid as it did voice in public were carefully qualified. And indeed business also practised discrimination over and above what the law required. Even a person as strongly opposed to socialism as Mangosuthu Buthelezi said to us that he did not want to hear about the supposed benefits of a free-enterprise system which was closed to blacks.

The second target market for our ideas was government. We knew that they were reading us. They were trying to make all their policies fit together into a coherent ideological and – so they thought – morally justifiable framework. But we didn't let them get away with anything. We exposed all the contradictions. We forced them to look at pictures of some of the horrors they were inflicting upon people. We made use of the violence in 1976 to say that there was no alternative to negotiation, that oppression wouldn't work.

We made sure that the views of black leaders were fully canvassed and reported. Even when people and organisations were banned and could not therefore be directly quoted, we quoted people likely to reflect their views. What lent weight to our opinion was our thorough knowledge of the complexities of apartheid laws, our insights into how policies actually worked on the ground, and our ability to deploy telling statistics to back our arguments.

It was a great time to be a journalist and George Palmer was a great editor.

* John Kane-Berman is a policy fellow at the Institute of Race Relations, a think-tank which promotes political and economic freedom. This article is an excerpt from his memoirs, Between two Fires, published last year by Jonathan Ball.