THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL OF SOUTH AFRICA

JUDGMENT

Case No: 678/12

Reportable

In the matter between:

ALLPAY CONSOLIDATED INVESTMENT HOLDINGS (PTY) LTD - First Appellant

ALLPAY FREE STATE (PTY) LTD - Second Appellant

ALLPAY WESTERN CAPE (PTY) LTD - Third Appellant

ALLPAY GAUTENG (PTY) LTD - Fourth Appellant

ALLPAY EASTERN CAPE (PTY) LTD - Fifth Appellant

ALLPAY KWAZULU-NATAL (PTY) LTD - Sixth Appellant

ALLPAY MPUMALANGA (PTY) LTD - Seventh Appellant

ALLPAY LIMPOPO (PTY) LTD - Eighth Appellant

ALLPAY NORTH WEST (PTY) LTD - Ninth Appellant

ALLPAY NORTHERN CAPE (PTY) LTD - Tenth Appellant

MICAWBER 851 (PTY) LTD - Eleventh Appellant

MICAWBER 852 (PTY) LTD - Twelfth Appellant

MICAWBER 853 (PTY) LTD - Thirteenth Appellant

MICAWBER 854 (PTY) LTD - Fourteenth Appellant

and

THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN SOCIAL SECURITY AGENCY - First Respondent

THE SOUTH AFRICAN SOCIAL SECURITY AGENCY - Second Respondent

CASH PAYMASTER SERVICES (PTY) LTD - Third Respondent

EZIBLUBHEDU INVESTMENT HOLDINGS (PTY) LTD - Fourth Respondent

FLASH SAVINGS AND CREDIT COOPERATIVE - Fifth Respondent

ENLIGHTENED SECURITY FORCE (PTY) LTD - Sixth Respondent

MOBA COMM (PTY) LTD - Seventh Respondent

EMPILWENI PAYOUT SERVICES (PTY) LTD - Eighth Respondent

PENSION MANAGEMENT (PTY) LTD - Ninth Respondent

MASINGITA FINANCIAL SERVICES (PTY) LTD - Tenth Respondent

THE SOUTH AFRICAN POST OFFICE - Eleventh Respondent

ROMAN PROTECTION SOLUTIONS CC - Twelfth Respondent

UBANK LIMITED - Thirteenth Respondent

AFRICAN RENAISSANCE INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT (PTY) LTD - Fourteenth Respondent

STANDARD BANK GROUP LIMITED - Fifteenth Respondent

NEW SOLUTIONS (PTY) LTD - Sixteenth Respondent

ITHALA LIMITED - Seventeenth Respondent

KTS TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS CONSORTIUM - Eighteenth Respondent

Neutral citation: AllPay Consolidated Investment Holdings & others v The Chief Executive Officer of the South African Social Security Agency & others (678/12) [2013] ZASCA 29 (27 March 2013)

Coram: NUGENT, PONNAN, THERON, PETSE JJA and SOUTHWOOD AJA

Heard: 15 FEBRUARY 2013

Delivered: 27 MARCH 2013

Summary: Public tender - whether irregularities invalidating contract - whether remedy to be granted if contract had been invalid.

ORDER

On appeal from North Gauteng High Court (Matojane J sitting as court of first instance).

1. The appeal is dismissed with costs.

2. The cross-appeal is upheld with costs. The orders of the court below are set aside and substituted with an order dismissing the application with costs.

3. Both in this court and in the court below the costs are to include the costs of three counsel where three counsel were employed.

JUDGMENT

NUGENT JA (PONNAN, THERON, PETSE JJA and SOUTHWOOD AJA CONCURRING)

[1] This is yet another case concerning a public tender. On this occasion the tender was for the payment of social grants. The body that invited the tenders was the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) established under Act 9 of 2004. SASSA and its chief executive officer are the second and first respondents respectively. The contract was awarded to Cash Paymaster Services (Pty) Ltd (CPS) - the third respondent. AllPay Consolidated Investment Holdings (Pty) Ltd - the first appellant - also tendered but was unsuccessful.

[2] Aggrieved at the award of the contract AllPay and various associated companies[1] - I will refer to them collectively as AllPay - applied to the North Gauteng High Court for orders setting aside the decision to appoint CPS and the contract that followed upon that decision. The relief sought was amended in the course of the hearing before the court below and I deal with that later in this judgment. For the moment it is sufficient to say that the court below (Matojane J) declared ‘the tender process [to be] illegal and invalid' but also ordered that ‘the award of the tender to [CPS] is not set aside'. AllPay now appeals the latter order and CPS cross-appeals the former order, in both cases with the leave of that court.

[3] It is as well at the outset to clear the atmosphere in which this case has been conducted so as to have certainty on what is before us.

[4] Whatever place mere suspicion of malfeasance or moral turpitude might have in other discourse it has no place in the courts - neither in the evidence nor in the atmosphere in which cases are conducted. It is unfair if not improper to impute malfeasance or moral turpitude by innuendo and suggestion. A litigant who alleges such conduct must do so openly and forthrightly so as to allow the person accused a fair opportunity to respond. It is also prejudicial to the judicial process if cases are adjudicated with innuendo and suggestion hovering in the air without the allegations being clearly articulated. Confidence in the process is built on transparency and that calls for the grounds upon which cases are argued and decided to be openly ventilated.

[5] The affidavits of AllPay evoke suspicion of corruption and dishonesty by innuendo and suggestion but without ever making the accusation directly and to a degree that has carried over to the heads of argument filed on its behalf. To clarify the position AllPay's counsel was asked at the outset of the hearing whether corruption or dishonesty was any part of its case, and that was unequivocally disavowed. It confined its case to what were said to have been fatal irregularities and it was on that basis that the appeal proceeded.

[6] But there have been many twists and turns in the case and there was to be another twist even after the appeal had been heard. Some three weeks after the hearing there arrived, unannounced, an application on behalf of AllPay to introduce further evidence into the appeal. AllPay said that the evidence establishes that the tenders were evaluated dishonestly. Its explanation for its earlier disavowal was that the evidence came to hand in admissible form only after the appeal had been heard.

[7] It is the practice of this court that parties may not file new material after the hearing of an appeal without the leave of the court. There must be finality in litigation and finality comes for the litigants once the appeal has been heard. That was conveyed to the attorneys of all the parties and they were directed to refrain from doing so. The response from AllPay's attorneys was to ask our leave to file the application formally. After reading the application we refused the request because even on its face, without hearing the other parties, there is no possibility that the application could succeed. I give the reasons for that briefly.

[8] The evidence sought to be introduced was an affidavit of a certain Mr Kay. He related a clandestine meeting with Mr Tsalamandris - an employee of SASSA who had provided administrative assistance when the tenders were evaluated - at a restaurant a year ago. In preparation for the meeting Mr Kay purchased a device with which he recorded their conversation.

[9] On the same day, after the conversation, Mr Kay wrote to the attorneys for AllPay. He told them in broad terms what Mr Tsalamandris had said and that he had a recording of the conversation. About a month later an anonymous account of the conversation was published in a Sunday newspaper.

[10] AllPay's attorneys listened to the recording shortly before its final affidavit was filed. They said ‘they understood the position to be that Mr Kay was, at least at that stage, not willing for the content of the recording to be made public or placed before the court' and for that reason the recording was not tendered in evidence. What was tendered instead was the newspaper article reporting the conversation, which was in due course struck out on the grounds that it was hearsay.

[11] There the matter rested until after the hearing of the appeal, when Mr Kay was asked, for the first time, to depose to an affidavit, which he readily agreed to do. I will not attempt to decipher the opaque reasons given for why Mr Kay was asked for an affidavit after the appeal had been heard.

[12] I am not aware of any case in which this court has admitted new evidence after an appeal has been heard. Be that as it may, even if the application had been brought before the appeal was heard we would certainly have refused it.

[13] It has been said many times that new evidence will be admitted on appeal only where the circumstances are exceptional. There would need at least to be an acceptable explanation for why the evidence was not placed before the court below. In this case we would also need an acceptable explanation for why the application was not brought before the hearing of the appeal. So far as that is concerned, at no time before the appeal was heard did AllPay even ask Mr Kay to depose to an affidavit. An explanation is given for why it did not do so when filing its affidavits in the court below, but AllPay gives no clear and forthright explanation for not having asked him before the appeal. On that ground alone the application would have failed.

[14] But that is the least of the difficulties. It is also trite that the evidence would need to be ‘weighty and material'.[2] In S v N[3] Corbett JA pointed out that in the vast majority of cases new evidence has not been allowed, and where it has been allowed the evidence has related to a single critical issue. In this case if the evidence were to be admitted the parties might just as well start the case over again. What is now sought to be introduced is a case entirely at odds with the case that was presented. What is more, far from being weighty, the evidence carries no weight at all, and would not be admissible even if it had been deposed to by Mr Tsalamandris himself.[4]

[15] The transcript discloses no admissible evidence of dishonesty. Some facts alleged by Mr Tsalamandris were not within his personal knowledge - he said that they were told to him by someone whose identity is not disclosed. Those allegations are hearsay that would not be admitted into evidence on any ground.` The remaining facts he disclosed were largely disclosures of what occurred in the process of evaluating the tenders, which are now disclosed in the voluminous record. For the rest the allegations of dishonesty made by Mr Tsalamandris were all inferences he drew from those facts. Inferences drawn by a lay witness are no more than expressions of his or her opinion that are not admissible in a court. It is for the court and not a lay witness to decide what inferences should properly be drawn from established facts.

[16] It needs to be borne in mind that the conversation took place a year ago before the record of the evaluation process was produced in this case. What occurred at the meeting is that Mr Tsalamandris related to Mr Kay some of the events that had occurred, made allegations of dishonesty by inference from the facts he disclosed, and invited Mr Kay to seek out evidence to establish those facts. The tenor of the conversation is captured by his statement that ‘if you put all these little pieces together you'll see'. Most of those ‘little pieces' are now a matter of record, some will be in the knowledge of AllPay if the events occurred, but have not been advanced, and others were capable of being established over the year the allegations have been known to AllPay. It is extraordinary that AllPay should disavow dishonesty and then think to place inferences before us through the mouth of Mr Tsalamandris.

[17] But in any event AllPay's advisers seem to overlook that the proceedings before us were brought on application. Final orders are granted in application proceedings only on undisputed facts.[5] I think it can be safely assumed that the inferences of dishonesty drawn by Mr Tsalamandris will be denied by the other parties - anything else would fly in the face of everything they have said in this case - in which event they would be irrelevant to the adjudication of the case.

[18] I do not think it is necessary to set out further reasons why the application could not possibly succeed. If proper evidence of corruption or dishonesty were ever to emerge I am sure AllPay's advisers are capable of advising it on remedies it might have. For the present I think we should put aside the diversion and continue to decide the case that was presented, in which dishonesty was disavowed.

[19] A criticism levelled by AllPay against SASSA highlights how a case of this kind ought not to be approached. In the heads of argument filed on its behalf AllPay took SASSA to task for what was said to be its ‘unseemly and spirited defence of CPS as its preferred candidate'. In the affidavits filed on its behalf it referred to SASSA's ‘partisan stance'. Those criticisms cast the case as a squabble between competitors as to who should have the bone, from which SASSA should keep out. Nothing could be further from the truth. Public procurement is not a mere showering of public largesse on commercial enterprises. It is the acquisition of goods and services for the benefit of the public. What is under attack in this case is SASSA's performance of that duty on behalf of the public. The interests of SASSA and those of the public are as material to this case as those of AllPay and CPS. When making any value judgments that might be required in this case those interests must also be brought to account.

[20] The procurement of goods and services by the state and other public entities is subject to various legal constraints. Section 217(1) of the Constitution requires all organs of state, when they contract for goods or services, to do so ‘in accordance with a system which is fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost effective'. That is taken up in the Public Finance Management Act 1 of 1999, which provides in s 51(1)(a)(iii) that the accounting authority of a public entity (which includes SASSA) ‘must ensure that the public entity ... has and maintains an appropriate procurement and provisioning system which is fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost effective'. It has also been held that public procurement constitutes ‘administrative action' as contemplated by the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act 3 of 2000 (PAJA) and must comply with the provisions of that Act.

[21] There will be few cases of any moment in which flaws in the process of public procurement cannot be found, particularly where it is scrutinised intensely with the objective of doing so. But a fair process does not demand perfection and not every flaw is fatal. It was submitted that the process of procurement has a value in itself, which must lead to invalidity if the process is flawed irrespective of whether the flaw has consequences, and extracts from various cases were cited to support that proposition. I do not think it is helpful to extrapolate from selected statements made in cases decided in a different context. The cases from which the extracts were drawn did not concern the process of tendering. I have pointed out that the public interest has a role to play in cases of this kind. It would be gravely prejudicial to the public interest if the law was to invalidate public contracts for inconsequential irregularities.

[22] Before turning to the course the case has taken and the issues that arise it is convenient to outline the background against which the contract was concluded, and the process that culminated in this contract.

[23] The state pays about 15 million social grants of one kind or another to about 10 million recipients each month.[6] At one time the task of paying those grants was the responsibility of the various provincial authorities. SASSA was established to bring the payment of social grants under a single umbrella. What SASSA inherited when the responsibilities of the provincial authorities were assigned to it was described in its affidavits as ‘disintegrated social security systems, lack of uniform grant administration processes, ineffective IT systems and interfaces, costly administration fees, fraud and corruption, and poor management of outsourced payment services'.

[24] At the time SASSA inherited its responsibilities most grants were being paid in cash by contracted service providers. Transporting large sums of cash to numerous payment points, some located deep in the rural countryside, presents substantial security risks in itself. If the money reaches its destination there is then the risk that payments might be claimed by people not entitled to grants, or in the name of beneficiaries who are no longer alive. When millions upon millions of rand are being paid out in social grants it goes without saying that there is the potential for enormous loss from conduct of that kind.

[25] Some risks can be reduced if payments are made electronically through the banking system but that presents other challenges. Banking is foreign to many recipients of social grants and their introduction to the banking system can be a cumbersome process. SASSA also needs to be certain that the bank accounts to which grants are paid are authentic and that the beneficiaries concerned are still alive. There is also a need for proper management information; there must be a proper means of accounting for the payments that are made; and so on.

[26] If an electronic payment system is capable of overcoming those challenges it is the preferred method of paying grants. At the time SASSA inherited its responsibilities about 37 per cent of grants were being paid electronically through the banking system by arrangement with the various banks. One of SASSA's objectives was to encourage cash recipients to convert to electronic payment.

[27] The invitation to tender - referred to as a Request for Proposals (RFP) - was directed at identifying service providers who would pay social grants on SASSA's behalf. The RFP had no fixed specification but instead invited solutions that would meet various stated objectives within certain parameters. There were a number of subsidiary elements to the service that was required - like providing adequate facilities for those recipients who queued to receive cash payments - but it was directed primarily at finding a payment solution that was convenient to recipients and limited the risk of theft and fraud.

[28] The RFP identified the scope of the work to be provided with reference to what were called ‘performance areas' that were described as:

- ‘Enrolment of eligible Beneficiaries, Grant Recipients and Procurators;

- Issuance of Beneficiary Payment Cards;

- Payment of grants;

- Provision of management information, including reconciliation of payment Data and the provision of adequate security during the entire payment process;

- The provision of adequate infrastructure at Pay-Points; and

- Phase-In Phase-Out Plan.'

[29] An effective means for avoiding theft and fraud in the payment process is to match payments against beneficiaries and recipients with reference to his or her unique biological features - referred to in the papers as ‘biometric verification' - typically his or her fingerprints or voice. The RFP made it abundantly clear in various places that a solution that embodied those features would carry considerable weight. Thus with reference to the registration of beneficiaries it recorded that

‘the intention of SASSA is to have all the Beneficiaries, irrespective of the method through which they receive their Grants, to be Biometrically identified'.

It went on to provide:

‘The minimum acceptable requirement during bulk and on-going enrolment is that all ten finger prints of Beneficiaries must be captured.'

It recorded that the biometric data captured during enrolment

‘will be used for matching and authenticating during payment process. The proposed solution must therefore allow or enable these business functions.... Biometric Data processing must allow one to many matching during enrolment and payment processing stages.... The enrolment Data will further be used to enable the life certification process and will become implicit during payments.'

So far as the ‘payment solution' being sought was concerned the RFP provided:

‘3.3.1 Payment Services of Social Grants must be secured, preferably, Biometric based. The Bidder's Proposal should provide detail on the measures that the Bidder/s will put in place to ensure that the right person is paid the correct amount.'

I return to that clause later in this judgment.

[30] The process that was employed for receiving and evaluating bids appears from the RFP supplemented by other documents that form part of the record.

[31] The process required sealed bids to be submitted by a specified date. Bids were to be submitted in what was called a ‘two stage envelope system'. That required documents setting out the ‘technical and functional' elements of the proposal (I will refer to that simply as the technical proposal) to be sealed in one envelope, and the ‘financial proposal and preferential points documents'[7] to be sealed in another envelope.

[32] Bidders were invited to submit bids for any number of provinces. If bids were made for multiple provinces then each bid was to be submitted separately. That was stated in the RFP as follows:

‘Bidder's may submit Proposals in respect of one or more Provinces specified in this RFP [all nine provinces were specified].

Each bid (per Province) must be submitted separately. For example, if Bidding for two Provinces, submit two separate bids'.

[33] Once bids had been submitted there would be a compulsory briefing session ‘where questions of clarification and/or queries concerning the requirements of this RFP will be addressed'. The briefing procedure envisaged that bidders would submit written questions by a specified date and that ‘responses and clarity to questions received' would be provided at the briefing session.

[34] Treasury regulations on state acquisitions required tenders to be evaluated by a bid evaluation committee (BEC) and a bid adjudication committee (BAC). The regulations required the state entity concerned to have a system for constituting those committees. The system employed by SASSA was contained in an internal circular issued by the Chief Financial Officer that directed how the committees were to be constituted and set out in some detail their functions and how those functions were to be performed.

[35] Bids would first be screened for compliance with the administrative requirements of the RFP. Those that survived would then be evaluated by the BEC, which would report and make recommendations to the BAC. The BAC would in turn make recommendations to the Chief Executive Officer, who was authorised to conclude a contract.

[36] There are cases in which the value to be had from goods or services is a compromise between their quality and their price. In such a case both elements would be weighed against one another simultaneously to reach the appropriate compromise. In this case bids were to be evaluated in two distinct stages, which demonstrates that the merit of the technical solution was foremost in SASSA's mind. Bids were first to be evaluated on the merit of the technical solution offered, without sight of the financial and preference-point proposals. Only solutions that crossed a substantial threshold - they needed to score 70 per cent - would proceed to be evaluated on their financial and preference-points merit. The way that was expressed in the RFP was that

‘bids will be evaluated against the solution criteria to determine whether or not these comply with the specified solution requirements. Depending upon the level of compliance, proposals will be accorded a scoring of 1 to 5 in line with the set criteria. Only bids that attain a minimum score of 70% of the total technical/functionality criteria will be considered for further evaluation for the financial and preference Points.'

[37] That does not mean that bidders who crossed the technical threshold would be at large so far as cost was concerned. The fee that SASSA was willing to pay was capped at R16.50 per transaction - a little more than half the average fee of R30 per transaction it was then paying.

[38] The RFP listed five criteria - with a number of sub-criteria in each case - against which the proposals would be scored. Once scored on a scale of 1 to 5 the scores would be weighted in calculating the overall percentage score. The weight attached to each of the criteria makes it clear that SASSA's primary concern was the solution offered for enrolment and payment. The five criteria, with the weight of each reflected in brackets, were ‘enrolment solution' (25 per cent), ‘payment solution' (40 per cent), ‘security services' (15 per cent), ‘phase-in phase-out' (10 per cent), and ‘risk mitigation' (10 per cent)'. The enrolment and payment solutions offered would thus contribute 65 per cent towards the target score of 70 per cent.

[39] The RFP envisaged that the evaluation of the bids would not necessarily be confined to evaluating the written documents. It provided that

‘bidders who submit proposals in response to this RFP may be required to give an oral presentation, which may include but is not limited to an equipment/service demonstration of their proposed solution/s to SASSA .... Demonstrations and presentations will be restricted to bidders that have obtained the minimum score of 70 % of the technical/functional evaluation phase .... Presentations and demonstrations will be afforded [so as to allow] the bidders an opportunity to clarify or elaborate upon their proposals. It should be noted that this phase should not be construed as contractual negotiations or submissions of material not submitted with the original proposal or be construed as an opportunity to change amend or vary the technical/functional solution.'

[40] The implication of that process is that some proposals might be so unmeritorious that they could be disqualified immediately. Others might be scored provisionally at 70 per cent or more, which would be subject to reassessment after the bidder had presented the proposal orally.

[41] Twenty one bids were received by the closing date. One was disqualified immediately and the remainder were referred to the BEC for evaluation. According to the report of the BEC bids were at first scored by each member independently. The various scores were then captured on a spreadsheet and discussed where necessary, particularly if there were large discrepancies.

[42] The bids were evaluated over a period of seven days. Both AllPay and CPS bid for all nine provinces. The evaluators scored the solution that was proposed by each and applied that score across all the provinces. After an initial evaluation over six days AllPay was given an overall score of 70.42 per cent and CPS was ahead of it at 79.79 per cent. The other bidders fell short and were disqualified from further evaluation.

[43] AllPay and CPS were then called to present their respective proposals orally. After the presentations CPS's score increased to 82.44 per cent and AllPay's score fell to 58 per cent, disqualifying it from the next evaluation stage. Satisfied with the CPS proposal on its financial[8] and preference-points merits the BEC recommended to the BAC, in a lengthy report, that it be awarded the contract for all nine provinces. The BAC accepted the recommendation and conveyed that to the Chief Executive Officer who concluded a contract for five years with CPS on 3 February 2012. The contract required CPS to commence its service on 1 April 2012.

[44] What confronts one at every turn in this case are certain undisputed facts that are material to all the arguments that have been advanced. The technical solution offered by CPS was considered by SASSA to be superior to that offered by AllPay in a material respect. The CPS solution was able to biometrically verify that every payment of a grant was made to an authentic beneficiary, at the time it was made, irrespective of the method of payment. The AllPay solution was not able to do that. AllPay was able to biometrically verify cash payments, but was able to verify the authenticity of beneficiaries paid electronically only once a year.

[45] In various parts of its affidavits SASSA described the position as follows:

‘[T]he solution presented by AllPay did not make adequate provision for biometric verification and the standardisation of services. This, in short, is the reason why the tender was not awarded to AllPay ...

...

The solution offered by [CPS] had the following important quality. It provided a uniform and equal facility for all beneficiaries, a uniform smartcard for all beneficiaries and applied to cash payments as well as electronic payments.

...

Additionally and importantly, the solution provides for biometric verification at all stages when payment is made to the beneficiary. By biometric verification is meant finger and or voice recognition at the payment stage. AllPay's solutions on the other hand provide different solutions for different categories of beneficiaries ....

...

The difficulty with AllPay's solution lies in the fact that its verification solution does not provide for authentication of banked beneficiaries. In other words, it continues to perpetuate the mischief [of fraud and theft] sought to be addressed in the prevailing situation, and which was pertinently addressed by the CPS proposal. AllPay's fundamental difficulty is that it has no solution for proper authentication of the banked beneficiary ... Moreover, beneficiaries are treated unequally in that a cash beneficiary has no flexibility to transfer to a banked system, and if he/she, after an arduous process does so, does not have the comfort of security arising from AllPay's inadequate solutions.

...

AllPay was unsuccessful in the bid because it lacked the expertise relating to enrolment solution and payment solution - the determinative criteria in evaluating a system sought by [SASSA] and which contained the essential elements to address the mischief of abuse by claimants for social grants who do not qualify'.

[46] Indeed, the undisputed evidence is that ‘the CPS solution as offered in its bid meets every single requirement stipulated in the RFP and addresses all the concerns raised by SASSA' and the AllPay solution did not, and that is why CPS was awarded the contract.

[47] It is not disputed that both bidders were treated equally throughout the process, whatever might have been its flaws. There is also no suggestion that that it was irrational, or unreasonable, or unlawful, for SASSA to want the solution that was offered by CPS in preference to that offered by AllPay. The most that AllPay was able to say was that its alternative solution could have won the day on its financial proposals had it proceeded to that evaluation stage. AllPay was not able to say that its proposal would indeed have proceeded to that stage absent the alleged irregularities that form the subject of its complaints.

[48] With that background I turn to AllPay's complaints. Most were upheld by the court below but its reasons for doing so did not materially elaborate upon the submissions made on behalf of AllPay and for that reason I do not refer to them each time.

[49] The case advanced by AllPay has shifted from time to time but there comes a point in litigation when litigants must fix their colours to the mast. AllPay did that in the heads of argument filed on its behalf. The case it advanced was presented under five headings and I deal with each in turn, in the chronological order in which the material events occurred.

THE COMPLAINTS

The Alleged Failure to Submit Separate Provincial Proposals

[50] I indicated earlier that the RFP required a bidder who was bidding for multiple provinces to submit separate bids for each province. Clearly what SASSA had in mind was that it would not consider bids that were open for acceptance only for multiple provinces or not at all.

[51] Both AllPay and CPS submitted bids for all nine provinces. AllPay alleges that the CPS bids were not separated for each province in conflict with the requirements of the RFP. It was submitted that it was unfair to AllPay to accept the bids in that form. Why that was so was not developed and I cannot see why that should be. No doubt the exclusion of CPS on that basis would have benefited AllPay but that is not what we mean by unfairness. The objection that was pressed more strongly - at least in the heads of argument - was that irregularity in the process is fatal for that reason alone - the general submission I referred to earlier that process has value as an end in itself. I do not need to consider that because there was no irregularity.

[52] It is not correct that CPS did not submit separate bids for each province as contemplated by the RFP. Its bid documents read together with the conditions for acceptance in the RFP make it perfectly clear that it was open to SASSA to accept its bid for any one or more provinces, which was the objective of the requirement. What occurred is only that CPS submitted one copy of its technical proposal that was to be applied to all the provinces.

[53] I do not think the RFP is to be construed as requiring a bidder who offered the same solution for all provinces to duplicate the document nine times. Commercial documents must be construed in a businesslike manner and that would not be a businesslike construction. There is no merit in this complaint.

The Composition of the Bid Evaluation Committee and the Bid Adjudication Committee

[54] The internal circular I referred to earlier required a BEC to comprise at least five people including a supply chain management (SCM) practitioner. The BEC that evaluated the bids in this case comprised only four members, none of whom was an SCM practitioner.

[55] AllPay's complaint is that the BEC was not constituted in accordance with the circular and for that reason its decisions were invalid. For that contention it relied upon Schierhout v Union Government (Minister of Justice)[9] and other cases.[10]

[56] Counsel's reliance upon Schierhout demonstrates why it is not helpful to cite cases out of context. That case concerned the exercise of statutory authority conferred upon a defined body. It goes without saying that in such a case only the body defined by the statute may lawfully exercise the authority. That was the same in Acting Chairperson: Judicial Service Commission. It has no application in the present case. The BEC was not a body constituted with statutory powers. It was merely a group of people brought together by SASSA to perform a task on its behalf - just as its employees do every day. Watchenuka and Ryobeza concerned something quite different and are not material.

[57] I do not understand the submission to be that the defect in its composition rendered its decisions unfair. Nor could such a decision have been sustained. The composition of a BEC was a matter within the discretion of SASSA. If the circular had required only four members without an SCM practitioner - which was its composition in this case -AllPay could hardly have said that was unfair.

[58] I understand the objection to be, once again, that because the composition of the BEC was in conflict with the circular it was irregular, and for that reason alone its decisions were invalid. I do not see how that can be. An act is not ‘irregular' for purposes of the law simply because one chooses to call it that. An irregularity that leads to invalidity is one that is in conflict with the law. It is because it is in conflict with the law that it is not able to produce a legally valid result.

[59] We were referred to no law that requires a BEC to be constituted in a particular way. We were referred only to the circular, which was not a legal instrument. It was no more than an internal document recording SASSA's standard policy. Perhaps it was an internal ‘irregularity' but it was not an unlawful irregularity. There is no merit in this complaint.

[60] The BAC comprised five members that included Mr Mathebula from the National Treasury. Mr Mathebula was not at the final meeting at which the BAC accepted the recommendations of the BEC. His absence, so it was submitted, was fatal to the BAC's decision.

[61] In support of that submission counsel relied again on Schierhout, and on Yates v University of Bophuthatswana.[11]

[62] The second and third meetings of the BAC were held on 9 and 25 November 2011 respectively. After the earlier meeting Mr Mathebula expressed various concerns to the chairman that he thought required further consideration. The chairman reported to the subsequent meeting on 25 November that he had met with Mr Mathebula and had discussed and recorded his concerns. He told the meeting that Mr Mathebula had been aware that the next meeting was scheduled for 25 November and had assured the chairman he would be present. As it turned out, Mr Mathebula was called elsewhere, and was absent from the meeting, to the annoyance of the chairman.

[63] The transcript of the meeting reflects that the remaining members were satisfied that they could continue and they did so. The concerns that had been raised by Mr Mathebula were placed before the meeting by the chairman and addressed in discussion with the members of the BEC. It seems they were satisfied with the responses and the BAC then recommended acceptance of the BEC recommendation.

[64] Again Schierhout has no application. Nor does Yates, in which the principle in Schierhout was applied in the context of a contract and takes the matter no further.[12] There was no law (I can leave aside a contract) that required a BAC to be constituted in a particular way. But in this case it goes further. It was pointed out in Schierhout that the question whether all members of a nominated body are required to be present when a decision is taken is a matter for the construction of the statute concerned. Applying that to this case, not all members of the BAC were required to be present when a decision was taken. Its terms of reference required a quorum of only three. There was no irregularity as contemplated by law - there was no irregularity at all - and this complaint has no merit.

The Failure to Assess the BEE Partners of CPS

[65] The bid of CPS reflected that three black empowerment companies were to manage and execute 74.57 per cent of the contract value. AllPay complains that the capacity of the companies to perform ought to have been assessed before awarding the contract.

[66] Counsel advanced this complaint as if it was self-evident that the failure of the BEC to assess the capacity of the three companies was unlawful but it is certainly not evident to me. SASSA was not required by law to assess the companies. There is also no basis for saying that its failure to do so impacted unfairly on AllPay. Nor can it be said that its failure to do so was irrational. It had reasoned grounds for its decision. It was alive to the risk of non-performance by the three associated companies and felt that the risk could be managed by imposing appropriate contractual consequences upon CPS. It cannot be said that that was not a reasoned decision. One might question the wisdom of its decision but the evaluation of the bid was its prerogative and a court cannot interfere only because it thinks its decision was unwise. This complaint also has no merit.

Bidders Notice 2

[67] The RFP was announced on 15 April 2011 with 27 May 2011 the closing date for submissions, which was later extended to 15 June 2011. The compulsory briefing session was held on 12 May 2011.

[68] Meanwhile AllPay posed various questions to SASSA and was told that they would be answered at the briefing session. In its founding affidavit AllPay complained that certain of its questions were never answered but that was not pursued before us and I need say no more about it.

[69] It will be recalled that various provisions of the RFP reflected that SASSA placed great store on biometric verification of payments.[13] One such provision was clause 3.3.1, which said that ‘Payment Services of Social Grants must be secured, preferably, Biometric.' The store that SASSA placed on biometric verification was announced again in a notice that was issued to all bidders shortly before the closing date that has been referred to as Bidders Notice 2. The notice stated its purpose to be ‘to give final clarity on frequently asked questions'. Amongst other things, the notice stated the following, under the heading ‘Registration (Enrolment)':

‘A Successful Bidder must register all Beneficiaries in a Province that has been awarded to the Successful Bidder, regardless of the Payment Methodology. A one to many biometric search must be conducted at the time of registration to ensure that a Beneficiary is not added to the database more than once'.

[70] On the day the notice was issued AllPay wrote to SASSA motivating a request for consideration to be given to extending the closing date for the submission of bids. The letter said nothing of that portion of Bidders Notice 2 that I have referred to. On 14 June 2011 SASSA announced that in response to numerous requests the closing date was extended to 27 June 2011. That meant bidders had seventeen days from the time the notice was issued to submit their bids.

[71] I do not need to examine the language of the two provisions. It has been accepted throughout this case that whereas clause 3.3.1 informed bidders that a solution offering biometric verification when payments were made, by whatever means, would be ‘preferable', the effect of Bidders Notice 2 was to inform them that only a solution having that feature would do. As it was expressed in argument at times, such a solution was ‘mandatory' under Bidders Notice 2.

[72] There was much debate on whether Bidders Notice 2 ‘amended' the RFP - which AllPay said it did - or whether it merely ‘clarified' the RFP - which SASSA said it did - but it seems to me that it is sterile to debate its correct classification. It is more helpful to examine what effect it had.

[73] Bidders Notice 2 did not change what had been asked for in the RFP. It merely narrowed the range from which SASSA would choose. Whereas bidders had been told before that a solution allowing biometric verification of all payments would be chosen above a solution that did not have that feature, Bidders Notice 2 now told those who had only the latter solution that they need not bid at all because their solution would not be chosen.

[74] Bidders Notice 2 made a difference to bidders only if they did not have the mandatory solution and were bidding against others who also did not have that solution. Before Bidders Notice 2 their bids would have been considered. After Bidders Notice 2 their bids would be rejected. But it made no difference to such a bidder who was in competition with a bidder who did have the mandatory solution. In that competition bidders were told by clause 3.3.1 that the mandatory solution would be chosen above other solutions. Bidders Notice 2 placed the bidder in no worse position. His or her solution would not have been chosen in any event. The notice informed the bidder only that he or she need not bid at all.

[75] In this case it is not disputed that AllPay did not offer the mandatory solution and that CPS did. On a proper application of the RFP SASSA was bound to accept the CPS solution in preference to that of AllPay even without Bidders Notice 2. That is what clause 3.3.1 had announced it would do. Indeed, it seems to me that had it accepted the AllPay solution CPS might have had good grounds to complain.

[76] There is a second problem that confronts AllPay so far as Bidders Notice 2 is concerned. If the mandatory solution had been announced in the RFP none of its present complaints could have been raised. Yet it indeed bid with notice that it was mandatory. One might ask, then, in what way it was prejudiced by the issue of the notice? Three contradictory answers are proffered in its affidavits.

[77] At one point it said that ‘it could, had it been informed [that a biometric solution was required], have amended its proposal to take account of the new requirement', implying that it was not informed. In the following paragraph it said that ‘had it been made clear that SASSA's tender now required monthly authentication by way of voice recognition, it would have been a relatively simple matter for it to adapt its offer accordingly'. In an affidavit that was filed later AllPay proffered yet a third explanation. It said that the ‘the eleventh hour change was prejudicial as it now required biometric verification on payment as an inflexible requirement, as such AllPay was not left with sufficient time to adapt its proposal to this fundamental shift'.

[78] None of those contradictory explanations can carry any weight. Contrary to the first explanation AllPay was indeed informed - seventeen days before the closing date - that a biometric solution was required. So far as the second explanation is concerned, AllPay wrote to SASSA on the day it received the notice, voicing various queries, with no suggestion that the meaning of the relevant part of the notice was unclear. As for the third explanation, AllPay said nothing to SASSA at any time, whether before or after it submitted its bid, to suggest that it had wanted to amend its bid but had not been allowed sufficient time to do so. Any suggestion that it could have provided the required solution would in an event not be credible. Clause 3.3.1 made it clear to all bidders that such a solution was preferred. Knowing that such a solution would at least give it preference, AllPay would hardly have held that solution back if it had had one, even without Bidders Notice 2.

[79] The true explanation for not offering the required solution emerged at the oral presentation of its proposal that I deal with presently. When questioned on the failure of its proposal to meet the requirements of Bidders Notice 2 none of the explanations now given was advanced for why that was so. AllPay's response was that it was not able to provide the required solution - indeed, it said that such a solution was not capable of being provided in South Africa.

[80] There are three essential facts in this case that create a dilemma for AllPay that none of its submissions address. First, SASSA was entitled to have the solution it required if that solution was available. Secondly, CPS offered that solution. Thirdly, AllPay was not able to do so. It seems to me in the circumstances that Bidders Notice 2 is a red herring in this case. Whatever notice had been given, it was not able to comply.

[81] The submissions for AllPay do not confront that dilemma but confine its case to one of process irregularity that is said to be fatal to the contract. I deal now with those alleged irregularities so far as they concern Bidders Notice 2.

[82] The first submission was that SASSA was not entitled to alter the RFP after it had been issued, for which counsel relied on Minister of Social Development v Phoenix Cash ‘n Carry,[14] and Premier, Free State v Firechem Free State (Pty) Ltd.[15] It goes without saying that once bids have been submitted it is unfair to evaluate them against altered criteria. As it was expressed in Firechem:

‘. . . [C]ompetitors should be treated equally, in the sense that they should all be entitled to tender for the same thing. Competitiveness is not served by only one or some of the tenderers knowing what is the true subject of tender. One of the results of the adoption of a procedure such as Mr McNaught argues was followed is that one simply cannot say what tenders may or may not have been submitted, if it had been known generally that a fixed quantities contract for ten years for the original list of products, and some more, was on offer.'[16]

That is what those cases were about. It is not what occurred in this case. Bidders Notice 2 was issued seventeen days before the closing date for bids.

[83] Then it was submitted that Bidders Notice 2 had no effect because it did not meet the formalities for amendments to the RFP provided for in clause 14.6:

‘Any amendments of any nature made to this RFP shall be notified to all Bidder/s and shall only be of force and effect if it is in writing, signed by the Accounting Officer or his delegated representative and added to this RFP as an addendum.'

[84] The RFP served two functions. One was to inform bidders what was required. The other was to bind a contracting party to its terms by incorporating it in the contract. That was provided for in clause 4.1 of the General Conditions of Contract, which provided as follows:

‘The goods supplied shall conform to the standards mentioned in the bidding documents and specifications'.

[85] The purpose of clause 14.6 of the RFP was clearly to serve that contractual function for the benefit of SASSA. It operated to protect SASSA from claims of the contractor that the bid documents had been informally amended. It was not intended to play any role in the informative function of the RFP - nor could bidders ever have thought it would. So far as Bidders Notice 2 purported to amend the RFP the amendment for that purpose required no formality, just as answers to questions at the compulsory briefing session required no formality.

The Scoring of the Bids

[86] Once having been scored provisionally the two bidders were invited to make presentations. AllPay complains that it was given short notice. It was telephoned at 19h00 on 5 Oct 2011 and told it must be in Cape Town on the morning of 7 October. CPS was given even shorter notice. It was telephoned at 22h15 the night before the presentations.

[87] Fairness cannot be evaluated in the abstract. Whether a person acts fairly or unfairly depends upon the situation with which he or she is confronted. AllPay made no complaint to the BEC that the notice given to it was inadequate. The BEC can hardly be said to have acted unfairly if it proceeded without having been asked not to do so.

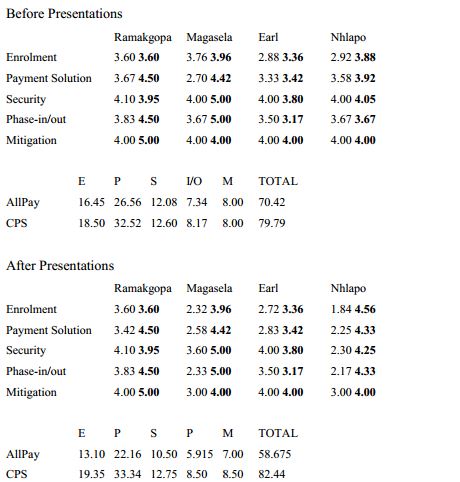

[88] AllPay was obviously unable successfully to field questions concerning the absence from its solution of biometric verification for all payments because it was not able to provide it. The best it could do was to suggest that it would be capable of doing so in the future. After the presentation the two bids were allocated final scores. The provisional and final scores that were given to AllPay and CPS respectively for each of the performance areas are depicted in the following tables. In the first and third tables the score for AllPay is in the left column and the score for CPS is in the right column in bold. The second and fourth tables reflect the weighted accumulated scores as a percentage. The abbreviations in those tables are: E = enrolment, P = payment, S = security, I/O = phase in/phase out, M = mitigation.

[89] In its affidavits AllPay took issue with the lowering of certain of the scores allocated by Ms Nhlapo and Mr Magasela. It was submitted that the final scores were irrational. When pressed on the issue counsel could offer no reason why the final scores were irrational other than that they were substantially lower than the provisional scores. Irrationality means the absence of reason. The fact alone that the scores were lowered, even substantially, does not infer that they were not founded on reason.

[90] Indeed, one does not need to look far to find why the scores of AllPay decreased. The report of the BEC recorded that the two bidders ‘provided at face value payment solutions that would meet SASSA's requirements' but that the two solutions ‘were substantially different in certain critical elements of their solution'. For that reason the BEC ‘decided that the scores of the two bidders will be accepted as preliminary scores pending presentations that would clarify elements of the payment solution'. I have already observed that when tackled on elements of the payment solution AllPay was not able to provide answers. One would expect, then, that their scores on those issues would be decreased materially. If there is anything remarkable in the scores it is only that those of Ms Ramakgopa remained much the same.

[91] In reply counsel for AllPay (who was not counsel who opened its case) pointed out that the record reflects a decision of the BEC that Bidders Notice 2 would be left out of account when the provisional scoring was done, and that the final scoring took account of the notice. He submitted that to score against different criteria on each occasion was irrational.

[92] I do not see why that should be so. The provisional scores were perfectly rational if they were reasoned against the criteria of the RFP alone. So were the final scores if they were reasoned against the criteria of Bidders Notice 2. The scores in each case cannot be said to be irrational - only that they were differently founded. The question is only whether it was permissible to score finally against the criteria of Bidders Notice 2, which it was.

[93] Our attention was also directed to certain sub-categories of the performance areas in which scores unrelated to payment were reduced. The explanations that were advanced for that were said to be astounding. I do not think it is necessary to relate the detail of the payments and the explanations. It is sufficient to say that we are not concerned with the quality of the reasoning but only with whether the decision was reasoned and not arbitrary.

[94] Finally, it was submitted that AllPay was treated unfairly because it was not told in advance of the issues to be addressed at the presentation and was not afforded a hearing. At precisely what point it ought to have been afforded a hearing was not made altogether clear but I understand the submission to be that it should have been informed that its provisional score was to be reduced and given an opportunity to respond before that occurred. In support of the submission that it was entitled to be told in advance of the issues and to have a hearing selected extracts dealing with natural justice were quoted from numerous cases.

[95] Extracts from cases decided in a different context are not generally helpful and that is so in this case. The rules of natural justice come into play when rights are affected or the person affected has a legitimate expectation that he or she will be heard. That was the case at common law[17] and it remains the case under PAJA. No rights of AllPay were affected by the decisions that were made - bidders do not have a right to a contract. Nor is there any basis upon which a bidder could be said to have a legitimate expectation of being heard in the course of a tender evaluation. If what is contended for were to be required, the evaluation of multiple tenders would be interminable.

Conclusion

[96] When all is said and done there is no escape from the facts I referred to earlier: SASSA was entitled to have the solution it required if that solution was available. CPS was able to provide that solution. AllPay could not. Absent all the alleged irregularities of which AllPay complains SASSA was entitled to award the contract to CPS. It seems to me that it would be most prejudicial to the public interest if inconsequential irregularities alone were to be capable of invalidating the contract. But I need not base myself on that in this case. In my view there were no unlawful irregularities. I think the court below was excessively receptive of the submissions made on behalf of AllPay. Its order ought not to have been made and the cross-appeal must succeed.

THE APPEAL

[97] In view of my decision on the cross-appeal it is not strictly necessary for me to deal with the appeal, but I think I should say something about it, if only briefly.

[98] The dilemma that arises when a contract is set aside was expressed by this court in Millenium Waste Management,[18] and later in Moseme Road Construction,[19] but what was said in the former case bears repeating: [20]

‘The difficulty that is presented by invalid administrative acts, as pointed out by this court in Oudekraal Estates, is that they often have been acted upon by the time they are brought under review. That difficulty is particularly acute when a decision is taken to accept a tender. A decision to accept a tender is almost always acted upon immediately by the conclusion of a contract with the tenderer, and that is often immediately followed by further contracts concluded by the tenderer in executing the contract. To set aside the decision to accept the tender, with the effect that the contract is rendered void from the outset, can have catastrophic consequences for an innocent tenderer, and adverse consequences for the public at large in whose interests the administrative body or official purported to act. Those interests must be carefully weighed against those of the disappointed tenderer if an order is to be made that is just and equitable.'

[99] We need no evidence to know the immense disruption that would be caused, with dire consequences to millions of the elderly, children and the poor, if this contract were to be summarily set aside. The prospect of that occurring has prompted the Centre for Child Law to intervene as amicus curiae in the case. We value the contribution they have made but they had no cause for concern. It is unthinkable that that should occur.

[100] Such an order was sought by AllPay in its notice of motion but the case has taken many turns. A new notice of motion was produced in the court below in the course of argument in reply. I do not intend setting out in full the new order that was sought. In essence AllPay asked for an order setting aside the contract and ordering SASSA to invite tenders again, subject to various directions as to the time by which various steps must occur. It asked for the order setting aside the contract to be suspended until that process was completed, the implication being that CPS should meanwhile be required to continue paying the grants.

[101] It was said that an order along those lines was granted in Millenium Waste but that is not correct. In that case a tender had been unlawfully disqualified and was not evaluated. What was ordered was only that the tender be evaluated, together with various arrangements that would remain in place until that had been done. How those arrangements came about does not appear from the judgment.

[102] The order asked for was produced only in the course of argument after all the affidavits had been filed. Neither SASSA nor CPS had an opportunity to file affidavits in response to the new claim. Counsel for AllPay submitted that a court is constitutionally authorised, once it has found conduct to be unlawful, to craft an order that is appropriate to the circumstances - which is correct - and that the court below ought to have done so. That court not having done so we were asked to craft one ourselves.

[103] This is not a simple contract as was the case in Millenium Waste. It is a massive contract with massive implications for fifteen million people and for SASSA and for CPS. The idea that a court is entitled to compel CPS to continue providing services against its will when its contract might at any time come to an end is problematic in itself. That the court below should have done that - or that we should do so now - without SASSA and CPS having had the opportunity to place facts before the court on the implications is not tenable.

[104] But even if this court was minded to do so, as we were asked to do, there is a fact that is decisive against it. I have pointed out that in Millenium Waste what was called for was only the evaluation of a tender. In this case AllPay wants the whole process to start again. If there had indeed been fatal irregularities in the evaluation of the bids that was no ground for SASSA to be ordered to invite new tenders. At most AllPay might have been entitled to an order that the bids be evaluated again without the irregularities.

[105] I think I have by now made it clear that if SASSA were to evaluate the bids absent the alleged irregularities there could be no complaint if it awarded the contract to CPS, for the very reasons it awarded the contract in the first place, and no doubt it will do so. No point would be served by ordering it to evaluate the bids if the outcome would be the same. Whichever way one turns in this case the facts cannot be escaped: CPS had a solution that SASSA was entitled to have and AllPay did not.

[106] There is no merit in the appeal. The court below was correct not to embark upon that hazardous excursion. As it turns out the order of the court below was unnecessary and we should set it aside but that is merely a matter of form.

[107] For those reasons

1. The appeal is dismissed with costs.

2. The cross-appeal is upheld with costs. The orders of the court below are set aside and substituted with an order dismissing the application with costs.

3. Both in this court and in the court below the costs are to include the costs of three counsel where three counsel were employed.

__________________

R W NUGENT

JUDGE OF APPEAL

APPEARANCES:

For appellants: G Marcus SC

D Unterhalter SC

M du Plessis

C Steinberg

A Coutsoudis

Instructed by:

Nortons Inc, Johannesburg

McIntyre & Van der Post, Bloemfontein

For 1st & 2nd respondents: S A Cilliers SC

N A Cassim SC

M C Erasmus SC

M Mostert

A Higgs

Instructed by:

The State Attorney, Pretoria

The State Attorney, Bloemfontein

For 3rd respondent: T W Beckerling SC

R Strydom SC

N Ferreira

J Bleazard

Instructed by:

Smit Sewgoolam Inc, Johannesburg

Symington & De Kok, Bloemfontein

For Amicus Curiae: T Ngcukaitobi

Z Gumede

M Bishop

Instructed by:

Legal Resources Centre, Johannesburg

Webbers, Bloemfontein

Footnotes:

[1]Who are the remaining appellants.

[2]Dormell Properties 282 CC v Renasa Insurance Co Ltd 2011(1) SA 70 (SCA) para 21.

[3]1988 (3) SA 450 (A) 458I-459A.

[4] Mr Tsalamandris did not depose to an affidavit.

[5]Subject to the qualification in Plascon-Evans Paints Ltd v Van Riebeeck Paints (Pty) Ltd 1984 (3) SA 623 (A) 635B-C.

[6]Some recipients receive multiple grants on behalf of multiple beneficiaries.

[7]A reference to points to be awarded for the advantages the proposal offered to historically disadvantaged persons.

[8]The price offered by CPS was marginally less than the capped sum of R16.50.

[9]Schierhout v Union Government (Minister of Justice) 1919 AD 30 at 44.

[10]Acting Chairperson: Judicial Service Commission v Premier of the Western Cape Province 2011 (3) SA 538 (SCA), Watchenuka v Minister of Home Affairs 2003 (1) SA 619 (C), Ryobeza v Minister of Home Affairs 2003 (5) SA 51 (C).

[11]Yates v Universiy of Bophuthatswana 1994 (3) SA 815 (BG).

[12]The conditions of employment of Yates, which were contractually binding on the University, provided that ‘the University may only terminate a contract of employment on the recommendation of a committee of enquiry [appointed by the Vice-Chancellor] ...'.

[13]Para 29 above.

[14][2007] 3 All SA 115 (SCA) para 2.

[15]2000 (4) SA 413 (SCA).

[16]Para 30.

[17]Administrator, Transvaal v Traub 1989 (4) SA 731 (A).

[18]Millenium Waste Management (Pty) Ltd v Chairperson of the Tender Board: Limpopo Province 2008 (2) SA 481 (SCA).

[19]Moseme Road Construction CC v King Civil Engineering Contractors (Pty) Ltd 2010 (4) SA 359 (SCA).

[20]Para 23.

Source: www.saflii.org.za

Click here to sign up to receive our free daily headline email newsletter