1.

On October 12, 2017 Judge Billy Mothle found at the end of the reopened (or second) inquest into the 1971 death of Ahmed Timol that Timol’s death “was brought about by an act of having been pushed from the 10th floor or roof of (then) John Vorster Square to fall to the ground” and that there existed prima facie evidence implicating Timol’s two interrogators, Captains Johannes Zacharias van Niekerk and Johannes Hendrik Gloy (both dead), for being responsible for this.

The judge also noted that Joao “Jan” Anastacia Rodrigues, now 80, had “on his own version, participated in the cover-up to conceal the crime of murder as an accessary [sic] after the fact, and went on to commit perjury by presenting contradictory evidence before the 1972 and 2017 inquests. He should accordingly be investigated with a view to his prosecution.”

Although Rodrigues was implicated as an “accessory” and/or as a perjurer, he was, on 30 July 2018, charged with murder by the National Prosecuting Authority. Since then, on March 28, 2019, Rodrigues has applied for a permanent stay of prosecution before a full bench of the Gauteng high court. As of today, no judgment has been issued.

The core of the state’s case may be said to have been presented by Advocate Torie Pretorius in his replying affidavit to Rodrigues’ stay of prosecution application. The state’s case avers that Timol “sustained at least 35 noted injuries, 27 of which were sustained” before the death fall. The trial court would now decide whether Timol, “with extensive bruising, a depressed skull fracture, a fractured left jaw, a dislocated left ankle” was able to rush to the window, open it, and jump out, as Rodrigues has claimed.

The theme of almost all the reporting and commentary on this case has been one of impatience at justice long denied. There has been very little critical scrutiny of the underlying basis for the prosecution. This is odd, for as we shall try to explain, there is a great deal about the version accepted by Judge Mothle that does not make particular sense.

2.

On the late evening of Friday 22 October 1971 two Indian men, travelling in a light-yellow Ford Anglia, were stopped at a routine police road block on Fuel Road in Coronationville, Johannesburg. In the boot of the car the police discovered hundreds of banned African National Congress and South African Communist Party leaflets, as well as copies of extensive communications with the SACP in London.

The two men – Ahmed Timol, a teacher and underground SACP operative, and Salim Essop, a third-year medical student at Wits – were handed over to the Security Police and taken to police headquarters at John Vorster Square.

The correspondence between Timol and his handlers in London was an intelligence windfall because it provided detailed descriptions of how the Party communicated with their operatives in South Africa. It also contained the names of many in the tightly knit Roodepoort Indian community that Timol had told the SACP he would like to draw into illegal work, or recruit into the Party, including Essop.

In almost all these cases Timol had not actually done so. The Security Police believed however that they had uncovered a secret Communist Party ring in the Indian community, one responsible for distributing often highly inflammatory propaganda aimed at inciting the black population to revolt violently against the white minority in South Africa.

Over the next few days the Security Police rounded up those named in the letters. They then began applying their usual interrogation techniques on those detained, most of whom were actually innocents. The Security Police were so convinced of the detainees’ guilt that denials of complicity were disbelieved and the torture rapidly escalated.

By the Sunday morning one of those detained, Kantilal Naik, had lost the use of his hands after being tied up and suspended from his arms and legs for an hour-and-a-half. On Tuesday morning Essop had completely collapsed on the floor of an interrogation room and had to be hospitalised. On Wednesday afternoon Timol himself plunged to his death from the 10th floor of John Vorster Square.

At the inquest held the following year Magistrate De Villiers ruled that Ahmed Timol had committed suicide and, dismissing the possibility that torture could have driven him to taking his own life, ruled that no one was to blame for his death.

This ruling was a travesty, given that the evidence of Timol’s fellow detainees – all of whom could have spoken about the torture they were subjected to – was excluded by the security laws of the time. Even more absurdly, evidence of Essop’s medical condition at the time of his collapse, already in the public domain, and available to ordinary newspaper readers, could also not be considered.

The Security Police witnesses meanwhile lied repeatedly throughout the inquest about how Timol had been treated. They falsely claimed, for instance, that Timol had neither been assaulted after his arrest, nor deprived of any sleep. So, on the one hand, the police said Timol had committed suicide while, on the other, they claimed he had not been tortured. In their efforts to explain why someone under no duress had decided to kill himself, they presented, among other false evidence, a fraudulent SACP document to court to try and square this circle. At the time their denials of any ill-treatment were widely regarded as deeply unpersuasive, even within the Afrikaner establishment, though it might have suited some to publicly pretend otherwise.

3.

Immediately after De Villiers announced his ruling in June 1972 Timol’s parents, Yusuf and Hawa Timol, told a Rand Daily Mail journalist that “we cannot believe our son committed suicide”. Their young relation, Imtiaz Cajee, subsequently fought a long battle to vindicate his late uncle and to demonstrate that Timol had been killed by the Security Police. Over the past few years he was joined in this quest by a group (“the team”) of investigators and human rights lawyers and organisations, including the Legal Resources Centre, Frank Dutton, Advocate Howard Varney, Webber Wentzel and Yasmin Sooka and the Foundation for Human Rights.

At the reopened inquest it would have been relatively simple to make the case that Timol’s death was one of induced suicide, the product of inter alia five days of unrelenting interrogation, torture, and sleep deprivation.

Proving a case of direct murder, as the team tried to do, was far more complicated: first, the finding from the original autopsy report that Timol had died as the result of injuries sustained in the fall remained incontrovertible. Second, all those named at the first inquest as Timol’s interrogators had died, taking their knowledge of what had actually happened with them to the grave. However, a former clerk from the Security Police, Rodrigues, who was still alive, had testified in 1972 that he had been alone in the room with Timol during his last moments alive, and had seen the detainee propel himself out of the 10th floor office window.

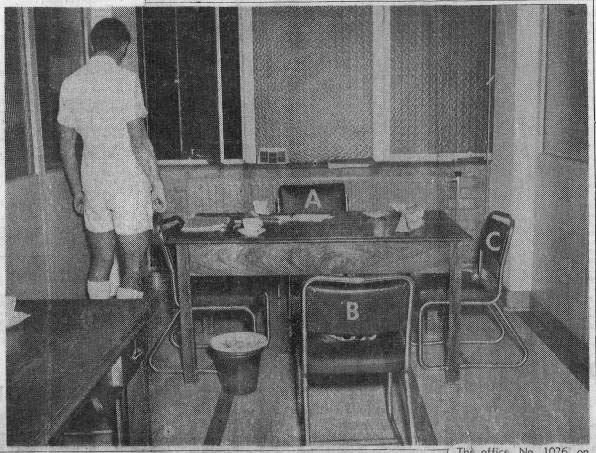

His version, to which he stuck at the second inquest, was that he had come to Johannesburg from Pretoria on the afternoon of Wednesday 27th October 1971 with the monthly salary cheques and a file for Timol’s two interrogators on that day, Gloy and Van Niekerk. Rodrigues took these – along with a tray with three cups of coffee for Timol, Gloy and Van Niekerk – into room 1026, and proceeded to wait, standing, for the following 20 minutes. At 3.50 pm Van Niekerk and Gloy then got up to go check on some information and asked Rodrigues to stay with Timol while they did so. Rodrigues told the first inquest that he then sat down on the chair facing Timol (chair "A" below), with the windows to his back:

“The Indian asked me if he could go to the toilet. He was sitting on the chair opposite me. We both stood up and I moved to the left around the table. There was a chair in my way [C]. When I looked up, I saw the Indian rushing round the table in the direction of the window. I tried to get around the table, but his chair was in the way [B]. Then I tried to get around the other way and another chair was in the way [A]. The Indian already had the window open and was diving through it. When I tried to grab him, I fell over the chair, I could not get at him.”

In making their case the team, led by Varney, wove together a powerful counter-narrative based largely upon “similar fact” and forensic medical evidence.

This ran as follows. Essop, with whom Timol had been travelling when caught by the police, was, after his arrest, “subjected to some of the most barbaric forms of torture ever recounted in a South African court. His four days and seventeen hours of torture was vicious, sadistic and unrelenting. By Tuesday morning Essop was in a comatose state and close to death.” On the Tuesday morning, 26th October 1971, he had to be rushed to hospital and his father “had to obtain an urgent court order to restrain the brutality.”

The day before his collapse, Essop had seen a “man with a black hood over his head being dragged by two Security Branch members, as he [the man] was unable to walk normally. Essop is certain that this hooded figure was Timol because he was familiar with his physique and height.” As Varney pointed out: If the Security Police tortured Essop to “near death”, why would they “treat the ‘big fish’ [Timol] with kid gloves”? Therefore, Timol must have been “tortured with equal if not greater ferocity than that endured by Essop”.

Another fellow detainee, Dr Dilshad Jetham, testified that she thought she had heard Ahmed Timol screaming on the evenings of the Sunday, Monday and Tuesday. “As the night of Tuesday 26 October 1971 wore on, Timol’s screams grew louder and became more desperate. He was shouting and crying, begging his torturers to stop.” According to Jetham, at dawn of Wednesday 27 October 1971, “Timol’s screams suddenly stopped”, followed by a great deal of scurrying about. This was at exactly 4am in the morning.

Two forensic pathologists, Dr Shakeera Holland, a senior Wits academic and the daughter of the renowned haematologist and FHR board member, Dr Errol Holland, and Professor Steve Naidoo, a former head of the Department of Forensic Medicine at UKZN, testified on behalf of the family. Holland said that several severe injuries recorded in the original autopsy report were “not consistent with a fall from height”. These, she said, called “into question the original inquest [finding] that the manner of death was ‘suicide’, therefore the finding must be challenged”. In his report and oral testimony, Dr Naidoo reached a similar conclusion, albeit on a somewhat different basis.

The forensic pathologists testified (variously) that certain hyoid bone, skull, jaw, ankle, and face injuries were also consistent with blows from a blunt object. Such evidence was devastating to Rodrigues’ version. As Varney and Pretorius put it to him, under cross-examination, how could he say Timol rushed to the window, given his severely dislocated ankle? How could he claim that Timol drank coffee when he had a broken jaw? How could he say he saw no visible injuries given that Timol’s face had been smashed with blunt objects? Rodrigues had no answer, other than that he could only speak to what he had seen.

“The finding of suicide,” Varney submitted to Judge Mothle in final argument, “rests exclusively on the evidence of Rodrigues whose evidence must be regarded as wholly unreliable. Indeed, the bulk of his evidence before both Inquest Courts was manifestly false.” He argued that by early Wednesday morning Timol had been as “similarly incapacitated” as Essop had been the previous morning, but “probably in a much more serious condition”.

Although not dead yet, he was probably unconscious, certainly incapacitated, and unable to talk, drink or eat (due to a fractured skull and jaw) and, in any event, unable to walk unaided due to the severely injured and dislocated ankle already incurred two days before.

These severe injuries not only disproved Rodrigues’ account, but also provided the missing motive for the murder. The Security Police had thrown Timol from the building several hours later, Varney suggested, to cover up what they had done and “to avoid the storm of criticism that would follow another ‘Essop’ occurring [with]in 24 hours”. Rodrigues had then been brought in to construct a story for public consumption, and thereby divert scrutiny from the interrogators/guards directly responsible for the brutal murder.

This version was accepted almost in totality by Judge Mothle. For the judge, the opinions of Doctors Holland and Naidoo were devastating to Rodrigues’ version, and to the assertion that Timol committed suicide. As he wrote in his judgment: “The injuries attributed to Timol prior to the fall, in particular on the toes and head, were such that he could not have moved with the alacrity and agility from the chair to the window without being assisted, as described by Rodrigues. Further, Rodrigues should have seen these injuries when, according to his evidence, he sat on a chair across the table opposite and facing Timol.”

As noted, the following year Rodrigues was charged for Timol’s brutal murder; and Rodrigues’ lawyers sought to avoid trial by launching a stay of prosecution application. This has been opposed by the state and the human rights establishment. The latter group’s view seems to be that the lack of direct evidence against Rodrigues is more than compensated for by the pure emotional force of this story. His clear guilt could further be demonstrated through inferential reasoning and through exclusion. Rodrigues places himself, and continues to place himself, with Timol in the latter’s last moments alive. His story of the suicide has been disproved by forensic experts, as impossible. If he was not intimately involved in the killing – and was simply an accessory after the fact – he could, quite easily, have come clean by now, given that “being an accessory” has long proscribed. That he has chosen not to do so, points to his deep involvement in the murder.

It is little wonder then that Rodrigues opted for a stay of prosecution, rather than have to answer for this murder before a trial court, or that South Africa’s human rights community, and many leading local and international journalists, are baying for his blood. The general sentiment is that the Timol family is not to blame for the fact that justice has been so long delayed, and that legal and factual technicalities that have arisen as a result should not be allowed to get in the way of Rodrigues’ trial, conviction and deserved punishment.

This leaves just one question. How much of the story presented at the second inquest was actually true?

4.

There is some background that is useful to bear in mind when it comes to the “similar fact” evidence.

As the ANC/SACP and others turned towards insurrection and the violent overthrow of the white state in the early 1960s, many of those arrested were brutalised by their interrogators, incurring severe physical injuries. Following the proclamation of 90-day detention without trial law in late June 1964, the Security Police introduced a new technique over the following months. As Bram Fischer described it in a memorandum for the SACP underground:

“Batteries of detectives working in shifts, firing salvoes of questions, forced detainees to stand in one spot without sleep and without sitting down, until they collapsed and agreed to make statements. This new technique is startlingly effective so far as we know, few who have been through this torture have been able to withstand it.”

Among the methods used to crack detainees and force them to betray their comrades and “name names” were sleep and sensory deprivation, solitary confinement, humiliating treatment, and the denial of food and drink. As George Bizos SC noted in No One to Blame?, his 1998 account of apartheid-era deaths in detention, with this shift in approach “[t]orture was concentrated less on the body and more on the mind, where the bruises were invisible even to the pathologist’s cold eye. Isolation, sleep deprivation, abuse and comfort in alternating doses, wore down a detainee’s mental defences as surely as an iron fist. And, of course, there was always the threat of physical pain to make the treatment that much more effective.”

Where pain was directly inflicted it was done so in ways, such as suffocation and electrocution, that would (generally) not leave any permanent physical marks. When it came to assaults, detainees were punched in the stomach and the chest but slapped in the face, as the jaw breaks easily. Bruises and abrasions could heal, and disappear, and any illegal assault could be denied. The detainee’s release, Bizos noted, inevitably took place after the injuries had healed, he had no witnesses to corroborate his story, and a team of security policemen “would claim how well they had treated the detainee, even to the point that they had spent their own money to buy him meat pies and cold drinks”.

These techniques were psychologically shattering, and led to numerous recorded attempted suicides, but they were designed to avoid severe injury, such as broken bones, that would leave inerasable (and un-deniable) physical traces. The detainees arrested at the same time as Timol all describe being subjected to these kinds of Security Police torture and interrogation techniques. No one was beaten with iron bars or hammers or had any bones fractured.

What though of Essop?

Varney told the inquest that “Essop was brutalised into a coma, within an inch of death”. Pretorius stated that as a “result of the continued and prolonged assault” on Essop “he was admitted to General Hospital and then Hendrik Verwoerd Hospital, near death and in a coma”. And Judge Mothle found that at the time of his hospitalisation Essop was “comatose” and had “severe injuries and was in a critical condition”.

Essop’s ill-treatment at the hands of the Security Police was certainly horrific, and it led to his collapse on the floor of the interrogation room on the morning of Tuesday, the 26th of October 1971.

However, the description of his having “serious injuries” at the second inquest is not supported by medical evidence of Essop’s condition, which is still lying in the national archives.

Essop was examined in John Vorster Square at around 9am by the Chief District Surgeon of Johannesburg, Dr Vernon Kemp. In this initial examination Kemp found Essop in a semi-conscious state and noted bruising on his face. Clearly concerned that his condition was the result of a brain injury caused by a physical assault, Kemp had him immediately taken by stretcher to the Moslem ward of the Non-European Hospital (NEH) in Johannesburg. He then arranged for a leading Johannesburg neurosurgeon, Dr CW Law, to examine him at 11.30am that morning.

Law was unable to take a history as Essop was not speaking. He however conducted a careful neurological examination to look for any sign that his condition was the result of an internal brain injury. Essop’s responses to these tests seemed however to be mostly normal. Blood tests and X-rays of his head and chest were also taken at around 12 am and these were all negative, with no fractures detected.

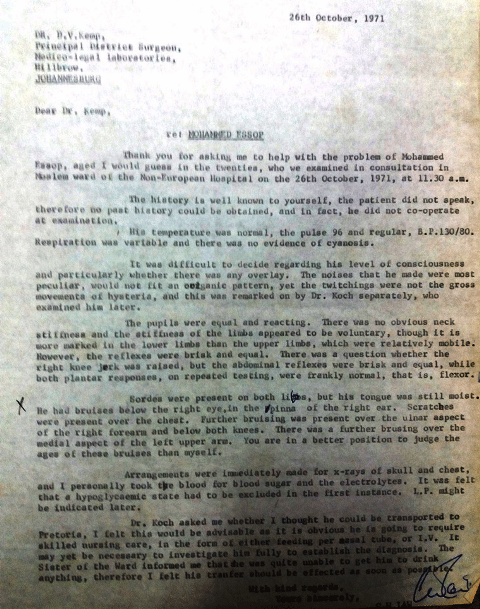

In his letter to Dr Kemp on the 26th October, dictated that lunchtime and setting out the results of the examination, Law noted that Essop’s “temperature was normal, the pulse 96 and regular, blood pressure 130/80. Respiration was variable and there was no evidence of cyanosis.” He also documented the following external injuries: “He had bruises below the right eye, in the pinna of the right ear. Scratches were present over the chest. Further bruising was present over the ulnar aspect of the right forearm and below both knees. There was a further bruising over the medial aspect of the left upper arm.”

Letter by Dr CW Law to Dr Vernon Kemp on the 26th October 1971 describing the results of his examination earlier that day.

Kemp concluded that Essop was suffering from “severe hysteria”, or what is known today as Conversion Disorder. In his testimony Law said that he had not made a diagnosis of hysteria, but this could not be excluded. He had suggested that a psychiatrist be called in because he did not think that a head injury was responsible for Essop’s condition. Law said that Essop appeared to be dehydrated and possibly in a hypoglycaemic state and these may have been contributing factors.

It was advisable for Essop to be transported to hospital in Pretoria, he said in his letter to Kemp, as “it is obvious he is going to require skilled nursing care, in the form of either feeding per nasal tube, or intravenously.” This was because the nurses were unable to get Essop to eat or drink. The testimony of doctors in Pretoria, more sympathetic to the Security Police, was that they thought Essop could be shamming.

The evidence of Kemp and Law was all extracted by the legal team for Essop’s father, led by Isie Maisels QC and Bizos, in his effort to interdict the Security Police from further mistreating his son. The Security Police meanwhile had done their best to try and hide it. In his 1998 book Bizos describes Law as an “honourable man” and Kemp as “honest” and suggested that both could be relied upon to tell the truth once under oath in the witness box.

In their judgment handed down on the 25th February 1972, Judges Theron and Marais upheld an earlier temporary interdict, issued by Judge Margo the previous year, and dismissed the claim of simulation deposed to by the police psychiatrist Dr Van Wyk. Theron and Marais ruled:

“Taking the history of his condition as deposed to by the medical witnesses, substantially supported by the evidence of the various nursing sisters who saw him on the 26th so ill as to require nasal feeding, we cannot but conclude that on the balance of probability the detainee suffered from the illness termed hysteria, and that this was induced by an assault him while in the custody of the first respondent [the police]. Consequently, in our view, therefore, the provisional order should be confirmed.”

The condition of Essop, as described by the doctors and nurses who treated him following his collapse, is a grim testament to the terrifying effects of the Security Police’s interrogation techniques. But their testimony does not ultimately support the team’s thesis. The actual physical injuries recorded by Law and Kemp, bruises and scratch marks, were superficial and not severe. Essop was also not in a coma, nor was he near death.

If one compares his mental condition with his physical condition one can see how well practiced the “professionals” of the Security Police had become in using, as Bizos put it in his book, “refined methods” to torment their “helpless captives”, while leaving only superficial external traces, which would soon heal and disappear.

5.

Essop’s recorded injuries at the time of his collapse are thus at odds with Timol’s – as described by the forensic pathologists at the second inquest. The great puzzle thrown up by their findings is this: There was a consensus at the first inquest that Timol’s severe and fatal injuries were consistent with the fall and had been sustained at the time of the fall. (This did not preclude the possibility that some were incurred before the fall, but this could not be proved.) As with Essop, there were other older superficial injuries present on the body, bruises and abrasions, which could be timed to either before or shortly after Timol’s arrest some four days before.

This was not just the position of the state pathologist Dr Nicholas Schepers but also of Dr Jonathan Gluckman, the independent pathologist employed by the Timol family (and the hero of Bizos’ book). It was also the position, in final argument, of the family’s legal representatives, Maisels and Bizos. The outlier on the forensic pathology at the first inquest was Professor Hieronymous van Praag Koch, the chief district surgeon of Pretoria and a favoured expert witness of the Security Police, who had already blotted his reputation in the Essop case. Koch tried to argue, disingenuously and unsuccessfully, that the older injuries had to have pre-dated Timol’s arrest.

In late November 1971 the Methodist Minister Donald Morton had fled South Africa. He had claimed, on arrival in Britain, that people who had seen Timol’s body had spoken of “finger-nails pulled out, the right eye missing, and testicles crushed”. In a short letter to the Observer, published in February 1972, Gluckman noted that “as the independent pathologist present at the autopsy of Mr Timol at the request of his family, it is proper for me to inform you that I observed none of the features described by Mr Morton, who quoted ‘sources that were impeccable’.” These allegations of mutilation later resurfaced when Hawa Timol repeated them at the TRC. In his 1998 book George Bizos wrote that “Gluckman would not have missed something like this and his integrity was beyond question”.

In short, the implications of the findings of the second inquest – which, seemingly incomprehensibly, Bizos himself publicly welcomed – were that Gluckman, Maisels, and Bizos, had somehow completely missed a series of severe injuries: a dislocated ankle, broken jaw, and depressed skull fracture, among many others.

There are some points that need to be noted about the forensic pathology at the first inquest. While in many respects the first inquest was rigged against the Timol family, there was, as far as can be ascertained, a completely even playing field when it came to the forensic pathology. The autopsy was conducted by Dr NJ Schepers on Friday morning, the 29th October 1971, with Dr Gluckman in attendance. They were equally able to examine the body, and both did so carefully. The priority was, first, to establish the cause of death, which was found to be multiple injuries incurred in the fall. And, second, to try and identify any injuries incurred before the fall.

Whatever Gluckman requested of Schepers during the autopsy, Schepers granted him. Numerous sections were taken from the body for histological analysis. Here again Gluckman was able to request that Schepers take particular samples and this was granted, and these were all later provided to Gluckman for analysis. That afternoon at 3pm Schepers went to the scene where he examined where and how the body had fallen, including the shrub it had hit and the various edges on the ground where it had landed. From the press reporting it is not clear whether Gluckman was in attendance. The autopsy report was signed off by Schepers on the 4th November.

At the first inquest itself the Timol family’s counsel, Maisels and Bizos, were advised by Gluckman as well as Dr H Shapiro, Professor of Forensic Medicine at the University of Natal. The assessor, Professor Ian Simson, was one of South Africa’s leading forensic pathologists. On one of the days all the forensic pathologists met and examined the slides of the histology together and reached consensus on what they saw. This was then read into the record by Simson. Maisels was in complete command of the forensic evidence as was Advocate Fanie Cilliers, advised by Koch, who appeared for the police.

During his testimony in court Gluckman was asked by Cilliers: “…do you think that the serious injuries and fractures that were found in the post-mortem, are consistent with having been caused with a fall?” He answered: “Yes, Sir.”

How then could Dr Holland and Professor Naidoo reach such a different conclusion to Gluckman et al?

6.

The first review of the autopsy report was conducted by Dr Holland. She was provided only with the original autopsy report and some post-mortem photographs. In addition, she went to the Wits archive library where she obtained Gluckman’s report on the histology, and some clearer slides of the injuries. In writing up her opinion she did not have any of the witness evidence as to where and how the body had fallen, nor the testimony by the various forensic pathologists at the first inquest. Naidoo meanwhile was also only given the autopsy report. He searched out online some of the witness statements, and transcripts from the original inquest (much of which was in Afrikaans), which he skimmed over. He says he did not have Gluckman’s report, although this had been read into the record.

In her report Holland identified several injuries that she viewed as inconsistent with the fall. These included: a depressed skull fracture of the left parietal bone; various facial fractures, including of the nose and both sides of the jaw; an injury to the hyoid bone; and a fracture of the first rib on the left. The methodology she used was to compare the severe injuries with the pattern of injuries that one “one would expect” from a fall from a great height. In her report she references several secondary sources to back up her opinion.

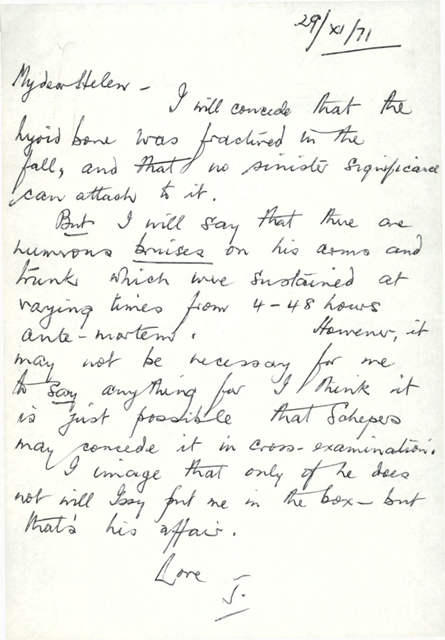

These do not always support her methodology or conclusions. For example, she states that the hyoid bone is “a relatively protected structure at the back of the throat and an isolated injury in this area would not be consistent with injuries caused from a fall from a height”. Interestingly, there is a letter in the Wits archives from Gluckman to the Progressive Party MP, Helen Suzman, who clearly wanted to be informed about the Timol inquest, in which he states that there was nothing suspicious about this injury.

Letter from Dr Jonathan Gluckman to Helen Suzman MP 29th November 1971. He subsequently adjusted his estimate of the time of the pre-fall bruises and abrasions.

If one goes to one of the two sources Holland cites, a 2004 paper by Elisabeth Türk and Michael Tsokos, it turns out that Gluckman’s assessment was not wrong. The authors state that “in falls from above 10 m, neck injuries like hematoma of the ventral neck muscles and fractures of the hyoid bone and the upper horn of the thyroid cartilage were seen in 33% of the cases.”

It seems that initially the team were going to argue that this injury meant that Ahmed Timol had been strangled before his death. But they could not in the end do so, as the report they commissioned from Professor Naidoo, produced two days before he and Holland gave evidence, also debunked this. He pointed out that this was probably a hyper-extension injury. Holland eventually admitted as much in her testimony to the inquest.

In his report Naidoo also refuted other claims by Dr Holland. He noted that the bruising to the forehead was, in fact, consistent with the fall. The body’s primary impact with the ground was with the “forehead and the area of the right shoulder/elbow”. This forehead bruising could, in turn, “be associated with the fracture line of the forehead, and the gross skull vault fractures that extended to the base of the skull and midline facial/nasal bones.”

There was more consensus between Holland and Naidoo on the isolated depressed skull fracture and the fracturing of the left lower jaw. The former fracture, Holland wrote in her report, “seems unrelated to the site of impact and is not associated with the linear base of skull fractures. Isolated depressed skull fractures are not commonly seen in falls from height and must be explained in the context of the fall.”

The secondary source she cites is not particularly relevant, not least because it deals with falls from a low height. It does advise against the methodology she was using however: “The forensic pathologist must not be dogmatic in interpreting the significance of certain injuries based only on the statistical analyses when determining the manner of death,” it states. “In cases requiring the distinction between homicidal and accidental fall injuries, the forensic pathologist must consider the police and death scene investigations to assist in the reconstruction of events” [our emphasis]. Yet Holland did not have any of this information when she drew up her report.

Another of her sources does go more directly to the point. It states:

“The type of skull bone fractures statistically significantly correlates with the height of fall (p>0.05). Heights beyond 7m are associated with higher frequency of multifragmental fractures. In general, these fractures are depressed on a wide surface part of the head that impacted the ground. Most falls from height involve impact on flat ground. Depressed comminuted fractures are caused by some localized and projecting traumatic agent on the struck surface. A high frequency of multifragmental fractures in falls from heights beyond 30m is thought to be the result of bouncing of the body following the primary impact.”

In other words, most falls are on a flat surface, in which case depressed skull fractures will not be present. They would however be expected where the head hit some kind of protrusion on the ground. Unless you know the surface on which the body fell, which Dr Holland did not, you cannot say whether a depressed skull fracture is consistent or inconsistent with a fall.

Somewhat more cautiously, Naidoo noted in his report that this particular “fracture pattern … does not appear to be fall-related. One is led to consider as a possibility an isolated impact that is distinct from the fall… The additional fracture that does not appear to be characteristic of a fall is the fracture of the mandible (lower jaw) at its corner/angle where it appears fragmented (broken into pieces).”

The basis on which Naidoo reached this initially tentative conclusion was that “it is unlikely that several impacts were received at different and opposition positions on the cranium as a result of falling if the body was unimpeded by any other intermediary obstruction/s during the fall.”

Both Holland and Naidoo were, in assessing the autopsy report, missing a critical piece of evidence – Dr Schepers’ description at the first inquest as to how the body had fallen, the surface on which it had landed, and how the severe injuries could (or could not) be matched to the fall. This part of the transcript was missing.

There is a Rand Daily Mail report which contains an almost verbatim account of Dr Schepers’ evidence to the first inquest in this regard. Timol had first fallen onto a shrub, several feet high, stripping it bare one side as he fell to the ground. He was found lying face down, with his head facing towards the right, so on its left side. Dr Holland did not know this, while Professor Naidoo failed to grasp the implications, and had assumed that the body had just fallen straight through the branches like a sack of potatoes.

According to Dr Schepers’ evidence, which was not disputed by Gluckman in his testimony (which is still available), Timol had actually impacted the stem of the shrub with his back. He was violently spun around, hitting the ground on his front right side with the head slightly lower than the body. His head had then swung around to hit the ground on the left side, hence the injuries to both the front and left of the skull. The depressed skull fracture was caused by an irregularity on the ground.

It turns out then that the injuries to the left side of the head, which Holland and Naidoo regarded as so suspicious, could in fact be explained in the context of the fall. This then leaves the issue of the dislocated ankle, which Naidoo regarded as so significant, and which remains central to the NPA’s case against Rodrigues.

The major concern of Gluckman during the original autopsy was to differentiate fall from pre-fall injuries. The primary way he and Schepers sought to do this was through histological analysis. The science is as follows: After someone is injured the healing process begins with inflammation and the influx of neutrophils (the main type of white blood cells) from between 4 to 6 hours, though it can begin before then. These can be picked up under the microscope. The healing process then progresses through various stages, again viewable under the microscope.

Abrasions can be dated fairly accurately, to within a range of a few days. But bruises far less so. The crucial point is that an ante-mortem injury, where there was no healing reaction, would have been incurred either at the time of the fatal fall or within a few hours beforehand. Numerous sections were taken from the skin and other organs of the body for this purpose.

Naidoo had a translation done of Schepers’ autopsy report. This described, in Annexure 1, the external appearance of the body and the condition of the limbs. There were 35 injuries described, which Naidoo numbered. In his report Naidoo wrote that the histological examinations “served a useful purpose by establishing that the wounds 8 to 35” were accompanied by a “histological vital reaction” and so clearly predated the fall from the building. He repeated this point in his testimony stating that “[t]hese eight to 35 wounds are what were largely used to do the histological examination of all the abrasions and bruises, and which were agreed [to] by all the Pathologists. Even [if] they differed on the age somewhat they did agree that all of them were healing wounds, and those were not fall related.” These included the bruising of the right calf (19), the dislocated left ankle (31), and the attendant bruises (32 and 33).

He further suggested that the left ankle injury was consistent with Essop’s testimony of seeing a hooded Timol being dragged along by Security Police officers, and so would have been at least two days old at the time of death. This point was crucial, as we have seen, because if Timol’s ankle had been dislocated in the way described, he would not have been able to dive out the window in the manner described by Rodrigues.

The problem with this analysis is that Naidoo completely misread the autopsy report – and the testimony of the pathologists at the first inquest – when it came to the histology. It is true that in (almost) all the sections discussed at the first inquest a healing reaction had set in. But this does not mean, as Naidoo seems to have assumed, that all the sections analysed showed such a reaction.

In his testimony Naidoo noted that his biggest limitation of his analysis was the absence of the reports of Gluckman and Koch. These were accessible to the team, Holland had had sight of them, and it is a mystery as to why they were not provided to Professor Naidoo.

In any event, if he had had Gluckman’s affidavit he would not have made this error because it explicitly states that “many, if not most, of the injuries which were examined microscopically showed no evidence of a cellular inflammatory reaction in relation to the injured area” (our emphasis). This meant that they were either sustained in the course of the fatal fall or were inflicted immediately before the fatal fall. In both cases there would not have been time, Gluckman noted, “for a cellular inflammatory reaction to occur”.

Even on the face of it, the autopsy report does not support Professor Naidoo’s interpretation. First, it would not be possible for all surface injuries on the body, excluding the head, to be pre-a-35-meter-fall injuries. Second, the autopsy report itself provides a schedule of the histological sections taken from the body. None of the sections taken from inside the body, including from the brain and hyoid bone, showed any healing reaction. There were seventeen skin sections taken (labelled from A to Q). The report notes that in several cases the bruises are “fresh”. So, in other words, there was no healing reaction detected.

The consensus reached at the first inquest – after all the pathologists had examined the slides together – was that there were only nine (not 27 or 28) sections where such reaction was present, with one clearly predating the arrest. These were all bruises and abrasions on the arms, right thigh, and chest, and were unrelated to any fractures. They did not include the bruising to the face, the left ankle, the toes on the left foot, or the bruise on the right calf. There was consensus too between Schepers, Gluckman and Simson that the abrasions where a healing reaction was present were between four and eight days old, the bruising between one and seven days. They were consistent, in other words, with Timol being viciously assaulted during the first day or so after his arrest. Given that Timol had not been injured prior to this contradicted the police version that Timol had been kept in “cotton wool”, as Maisels referred to it, while in detention. The police were thus lying about this, and who knows what else.

The histological evidence, read properly, also contradicts the narrative account that the team presented to the second inquest, which was accepted by Judge Mothle, and which now forms the basis of Rodrigues’ prosecution. If for instance Timol’s ankle had been dislocated on the Monday it would have soon become massively swollen. The pathologists at the autopsy would have seen that it was an old injury, and this would have been confirmed by the histological analysis. It was clearly regarded as fresh injury however, and so not even discussed at the first inquest.

This injury was also regarded as consistent with the fall, at the time. As the RDM report on Schepers’ testimony stated: “The left groin was bruised and the left ankle was strained, probably by hitting the right leg. Large bruises on the front of the right lower leg were probably also caused when the left foot hit against the right leg during the fall.” (Timol’s right shoe was knocked off by the impact.)

Equally, if Timol had been beaten with blunt objects and physically incapacitated by Security Police interrogators by 4am on the Wednesday morning, as Varney suggested, inflammatory reactions would probably have set in by the time he was supposedly thrown to his death, at some time after 10 am, and certainly if this had occurred twelve hours later. Again, these would have been picked up by Gluckman’s histological examination.

In other words then, there turns out to be no actual basis for the claims made, at the second inquest, that a number of the serious injuries documented in the first autopsy (of the jaw, ankle and skull) were incurred several hours or even a couple of days before the fall, or were inconsistent with the fall. This was the product of the pathologists at the second inquest being asked to draw their conclusions based on only a part of the forensic evidence, and of making several serious errors in their analysis as a result.

7.

There is further evidence from the first inquest, and the Essop interdict case, that contradicts the timeline presented to the second inquest by Varney and the team. As noted earlier the supposed motive for the murder of Timol was that the Security Police, having gone too far in their interrogation at 4am in the morning, were worried about the “outcry” that would follow “another Essop”. So instead of immediately calling in Kemp, as they had done twice previously over the past few days, and would do later that day, they decided instead to kill Timol by throwing him off the top of the building several hours later.

The problem with this theory is that Essop’s hospitalisation was still a secret at that time. It was only on the morning of Wednesday 27th of October 1971 that Ismail Essop was tipped off by the journalist Mike Norton of The Post that his son was lying ill in the Cassim Adam Ward at the HF Verwoerd Hospital in Pretoria. They had then rushed to the hospital arriving at noon (so after Timol’s death on the team’s timeline.)

The matron denied that anyone with his son’s name was there, but they were able to establish that the Security Police were guarding a suspect in Room 8. When the ward re-opened for visitors at 3pm Ismail Essop clambered onto a bed that had now been placed in front of the door and peered through the glass panel above the door and saw his son Salim lying at the far end.

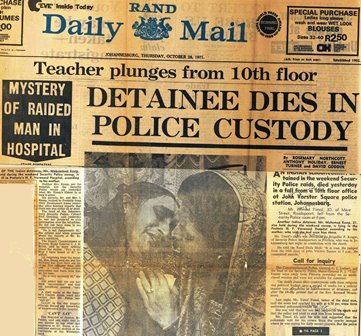

The news of Essop’s hospitalisation and Timol’s death broke within hours of each other. They were both reported on the front page of the Rand Daily Mail the following morning. The death of a detainee in detention was always a big deal, but the outcry was greatly magnified by the concurrent breaking of the news of Essop’s condition.

The front page of the Rand Daily Mail, 28th October 1971

It is worth noting here that the finding at the second inquest that Timol had fallen to his death in the morning was based upon very flimsy grounds, and apart from being utterly improbable, was contradicted by witness and forensic evidence.

Timol fell in full view of everyone, ordinary police and civilian alike, who was in that side of the building at the time, as well as of anyone who happened to be passing by on the street. The approximate time of death (4pm) was reported in the newspapers the following day. If the Security Police had lied about the time of death, there would have been innumerable witnesses who would have been able to contradict this. This issue would have been picked up by the press and raised in parliament or by Maisels and Bizos at the first inquest. There was nothing stopping the witnesses who materialised at the second inquest, claiming that they remembered the fall as having occurred in the morning, from tipping someone off about this, at the time.

The time of the incident was also confirmed at the first inquest by non-Security Police witnesses such as Brigadier Cecil William St. John Pattle, a Brigadier in the CID (the detective branch), who conducted a preliminary investigation; and Kemp himself, who was also called in again by the Security Police shortly after the fall. Kemp noted, in an affidavit, that when he reached John Vorster Square at just after 4pm, that Timol was “pas dood” (just dead.)

There are a few markers allowing an experienced district surgeon, as Kemp was, to tell from the state of the body whether someone had “just died” or been killed several hours earlier. These include the cooling of the body after death (algor mortis), whether the blood on the body and clothes of the deceased was coagulated or not / wet or dry, and the settling of the blood within the body (livor mortis).

Furthermore, on the Security Police version Timol had been writing a seven-page statement on the Wednesday up until shortly before his death in the afternoon. This document, which was in Timol’s handwriting, was submitted as an exhibit to the first inquest and there is no question about its authenticity. He had also eaten lunch on that day, something confirmed by the autopsy, which recorded that partially digested slap chips had been found in his stomach. These two pieces of evidence (as they stand) contradict the team’s timeline, and the claim that Timol had been physically incapacitated by 4 am and was killed not long after 10 am.

8.

The focus at the second inquest, we suggest, should have been, as far as possible, on the last few hours and minutes of Timol’s life before the fall, just before 4pm – to which there was a still a living witness, Rodrigues. It was here that the answer could perhaps still be found to the question of whether Timol took his own life, and if he had, what drove him to do so. By the time he took the stand however the entirety of Rodrigues’ version had been written off as palpably untrue, largely based upon the misinterpretation of the original autopsy report.

One of the lessons to be drawn from the reopened inquest is of how a judicial process can veer wildly off track.

A large part of the evidence presented to the first inquest – including some essential parts of the forensic evidence – was missing from the second. Most of the key witnesses were deceased, including the original forensic pathologists. The main suspects, Timol’s interrogators, were unable to defend themselves in court, being dead. Those witnesses still alive were recalling events of close to five decades previously. Revisiting the past, in such circumstances, requires a careful and rigorous process. But the second inquest was anything but this.

It was heavily one-sided, with almost all the evidence led by the Timol family’s legal team. They were clearly, and understandably, out to prove a thesis. However, as we have explained, much of the “powerful new evidence” presented involved the erroneous reinterpretation of old evidence, such as the autopsy report, from the first inquest.

The similar-fact evidence of torture cut both ways. It disproved the Security Police’s “cotton wool” assertions from the first inquest, but it opened the door to the possibility that such torture (or the fear of its resumption) could have led Timol to take his own life. It also did not support the team’s account of brutalisation and severe injury.

The National Prosecuting Authority meanwhile acted in a supporting role to the Timol family, failing to commission an independent opinion on the forensic evidence for example, and parroted the family’s case in their final arguments. The media was hearing what it wanted to hear and so failed to ask any of the obvious and hard questions.

There was thus simply no testing or careful scrutiny of any of the evidence presented by the family’s legal team. Despite Rodrigues’ counsel, Advocate Coetzee, raising several red flags in cross-examination and final argument about the team’s case, these were not taken seriously, either by Judge Mothle or the press.

As the inquest progressed a kind of recklessness took hold with regards to how the probabilities and the facts were dealt with. The conceit seemed to set in that the purpose of the inquest was not to try and establish the truth, difficult as that was always going to be, but rather to pronounce upon it. This culminated in the utterly implausible claim, accepted by Judge Mothle, that Timol had fallen to his death in the morning.

The second inquest was thus not able to detect and challenge the numerous factual blunders that ultimately elbowed their way through the inquest and into Judge Mothle’s ruling. One result was that, at the end of the inquest, we were probably further away from understanding what actually led to Timol’s death than we were at the beginning. The Timol family attained the finding that they were seeking, but on a deeply unsatisfactory basis.

If the state had just left the matter there, one could perhaps say that some kind of rough and messy justice had been achieved: the faults, inadequacies and dubious evidence of the first inquest being counterbalanced by the faults, inadequacies and dubious evidence of the second.

But the false evidence of the second inquest – having been laundered through the Mothle judgment – is now being used by the NPA in the deadly serious matter of a murder prosecution. The prosecutors, journalists and human rights organisations pursuing Rodrigues’ conviction and imprisonment are no longer acting recklessly towards the truth, but recklessly with regards to someone else’s life.

"Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose".

___

Previous articles in this series:

The curious case of Quentin Jacobsen (III)