Will ‘Gupta’ now enter the South African lexicon as a by-word for financial and corporate intrigue? Certainly the family name has become synonymous across the country with Machiavellian business machinations and has been conflated with Zuma by the EFF into ‘Zupta’.

Presently the Guptas are the subject of daily attention: the latest bombshell, delivered by Mcebisi Jonas, Deputy Minister of Finance, claimed the family offered him the job of Finance Minister shortly before Nhlanhla Nene was removed.

Attention on the family and their dodgy relationship with the President will certainly gain momentum as local government elections draw nearer. The Gupta family’s questionable business dealings and apparent power, together with Nkandla, provide fodder for those seeking to remove Jacob Zuma.

The story is gaining momentum: the SACP has recommended a judicial commission to probe issues relating to the Gupta’s business deals as well as what they term the ‘corporate capture’ of government by businesses. While such an investigation will go beyond the family, it is likely that their name will survive as a symbol of ‘corporate capture’.

Not since ‘Hoggenheimer’ in the early twentieth century has a name achieved such traction. In that case, however, Hoggenheimer was fictitious. Indeed he was a cartoon caricature, in the tradition of European cartoons of the late nineteenth century when international capital was personified in a vulgar, bloated and Semitic-looking caricature.

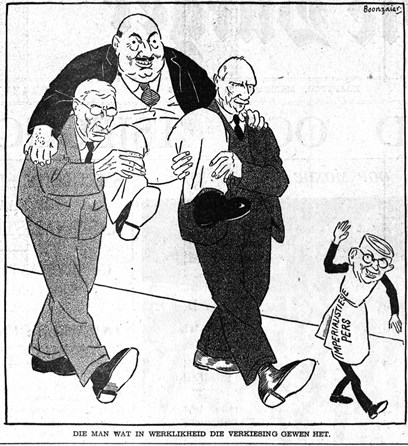

In South Africa, Hoggenheimer appeared precisely at a time the Witwatersrand mining magnates appeared to dominate domestic politics. From the ‘Goldbug’ sketches of Heinrich Egersdörfer to the cartoons of D.C. Boonzaier, the overweight and diamond-studded Randlord was depicted as having inordinate power.

It was only after the Anglo-Boer War, however, that the cartoon caricature was given the appellation Hoggenheimer: his first appearance was in the South African News, a Cape Town daily, on 24 September 1903.

In a short space of time he assumed national notoriety, increasingly depicted as grossly Semitic and overweight. Indeed, with hindsight, the crudeness of the caricature served as a rough gauge of anti-Jewish and anti-capitalist sentiment through the first half of the twentieth century.

Because Boonzaier was the cartoonist responsible for the Hoggenheimer caricature, and because he maintained an association with the caricature for close on four decades, it has been assumed that Hoggenheimer was his creation. In fact this is not the case.

The distinction belongs to the English playwright Owen Hall (a non-de-plume for James ‘Jimmy’ Davis) who created the Jewish millionaire, Max Hoggenheimer, in his West End musical comedy, ‘The Girl from Kays’ which opened at the Apollo Theatre in London on 15 November 1902.

This story of a show dancer who succeeded through her winning ways in capturing the heart of a South African millionaire played for 432 performances before being brought to South Africa, where the loud-mouthed Hoggenheimer became an instant favourite with South African theatre-goers. By all accounts, the English comedian, W.W. Walton, delighted audiences with his portrayal of the wealthy Jewish financier of Park Lane.

The caricature figure of Hoggenheimer is carried on the shoulders of JBM Hertzog and Jan Smuts following the United Party's victory in the general election of 1938. Cartoon by DC Boonzaier from Die Burger, 23 May, 1938.'

It was ten days after ‘The Girl from Kays’ opened at the Good Hope Theatre in Cape Town that Boonzaier (an avid theatre-goer) published his first Hoggenheimer cartoon, acknowledging Owen Hall’s creation by appending the caption ‘with apologies to “The Girl from Kays”’.

With the regular publication of these cartoons and the production of the play in major centres of South Africa from September 1903 to November 1904, Hoggenheimer soon personified acquisitive international capital, bent on self-aggrandizement. Thereafter he became a regular feature in the South African News, following the cartoonist as he worked for The Cape, The Observer, The Cape Argus, De Voorloper, New Nation and Die Burger.

No doubt the Anglo-Boer War and the power of mining capital ensured notoriety for the cartoon caricature, not to mention a deep vein of hostility towards immigrant Jews. To be sure, it is not without significance that when denigrating the east European Jewish immigrant, journalists used the same east European accent that was represented in the speech ‘bubbles’ of the garrulous Hoggenheimer caricature.

It is also noteworthy that during the Rand Rebellion of 1922, pamphlets aimed against the capitalists featured ‘Hoggenheimer the Jew’. By then the illustrious name of Oppenheimer - similar in sound and intonation to Hoggenheimer - no doubt helped to consolidate and ensure the impact of the fictional character.

Like Hoggenheimer, the Guptas too have struck a responsive chord at a moment in South African history when corruption looms large. Hardly a day goes by without reference to the Indian family. ANC Secretary General Gwede Mantashe has gone so far as to talk of a ‘national obsession’ with the Guptas.

That obsession has now been taken to new heights with the disclosures of Mcebisi Jonas. With corruption endemic and attention firmly focused on the Guptas, we can be sure that the name will be embedded in the consciousness of South Africans for decades to come. Hoggenheimer has a successor.

Milton Shain is Emeritus Professor of Historical Studies at the University of Cape Town. His latest book, A Perfect Storm. Antisemitism in South Africa 1930 – 1948, was published by Jonathan Ball in 2015.

This article first appeared in Die Burger, 7 April, 2016