Introduction

In the recent obituaries of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela published in the British and American press reference was almost invariably made to her infamous 1986 remark that “with our boxes of matches and our necklaces we shall liberate this country.”[1] The necklace in this context involved placing a petrol or diesel filled tire around the neck of an individual and then burning them to death.

Her stance is commonly contrasted with that of other African National Congress leaders, including Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo, who were supposedly appalled by her remarks. As the New York Times noted in its obituary her call “shocked an older generation of anti-apartheid campaigners. But her severity aligned her with the young township radicals who enforced commitment to the struggle.”

Her remarks are also commonly described as being at odds with the policy of the ANC at the time. In its submission to the Truth & Reconciliation Commission in 1996 the organisation itself stated that the use of “extreme methods” to “neutralise the enemy, which included deterring and punishing collaborators, was perceived by many as an entirely justifiable act of self-defence.” But, it continued, “Such extreme methods, including the 'necklace' method, were never the policy of the ANC or UDF/MDM.”

In its second submission to the TRC, in May 1997, the ANC further claimed that in the mid-1980s it had “strongly disapproved of some of the methods chosen by people to kill informers and other collaborators, particularly the ‘necklace’, and stated this on more than one occasion.” It added though that it would not condemn those involved in the struggle, at that time, who believed they were “making their contribution by ridding communities of informers and those amongst them who directly collaborated in apartheid violence.”

In Western eyes at least, the ANC’s dissociation of itself from this practice left Winnie Madikizela-Mandela standing alone in the dock before the judgment of history. She is the only ANC leader, of that time, regularly condemned for having encouraged necklacing. If one goes back and revisits the history of that period however it is very clear that this is a great unfairness to her.

To understand why, it is necessary to bear in mind a basic mechanism by which ANC/SACP propaganda historically operated. During the relevant period in the mid-1980s ANC propaganda was, metaphorically speaking, broadcast on two separate frequencies, for consumption by two different audiences, with two incompatible messages being conveyed.

On the one the ANC broadcast a message of moderation to its confirmed and potential liberal sympathisers in the West, people who were appalled by apartheid but who did not want to think too hard about the alternative the ANC was really offering. This largely involved telling Western (and increasingly white South African) intellectuals, politicians and journalists in private what they wanted to hear, and maintaining an ambiguous posture on certain fraught issues in Western public fora.

On the other the ANC communicated to its own cadres its actual revolutionary racial-nationalist ideology and strategy. This was set out in the ANC and SACP journals, such as Sechaba and the African Communist, and in internal policy and strategy documents. The ANC’s instructions to their supporters and members on the ground in South Africa were conveyed through pamphlets smuggled into the country, couriered information, and most importantly in this period Radio Freedom broadcasts. ___STEADY_PAYWALL___

1985: How necklacings began

In early September 1984 mass protests had broken out in the Vaal triangle, and then spread across South Africa, following the adoption of the new constitution, which failed to extend meaningful rights to black Africans at national level even as it accommodated (to a limited degree) Coloureds and Indians in national government. The only rights that had been extended to black South Africans outside the homelands were at the local council level, and these immediately discredited themselves by promulgating high rental increases. The ANC in exile sought to capitalise on these protests, and guide their direction, by calling for the country to be made “ungovernable.” This was a reiteration of the message of its January 8th statement earlier that year in which the party’s NEC had said that its goal was to create “conditions in which the country becomes increasingly ungovernable,” something which required first attacking “those parts of the enemy administrative system which we have the power to destroy, as a result of our united and determined offensive. We must hit the enemy where it is weakest.”

In the ANC’s January 8th statement of 1985 Oliver Tambo noted that over the past year “impressive strides” had been taken “towards rendering the country ungovernable. This has not only meant the destruction of the community councils. Our rejection of the apartheid constitution was in its essence a reaffirmation of our rejection of the illegitimate rule of Botha and his clique….In this coming period, we shall need to pursue with even greater vigour the task of reducing the capacity of the colonial apartheid regime to continue its illegal rule of the country.”

Over the next few months Radio Freedom would, in its broadcasts, exhort ANC supporters on the ground in South Africa to organise themselves into small units, arm themselves with whatever weapons were at hand (from Molotov cocktails to stolen guns), and go out and attack policemen and councillors and other “collaborators” in their homes and elsewhere and so “eliminate” the “puppets who are roaming amongst us within.”

In late April 1985 the ANC National Executive Committee issued a statement titled “The future is within our grasp” – drafted by Joe Slovo - which was repeatedly broadcast over Radio Freedom. A précised version of which was distributed in leaflet form by the ANC underground across South Africa. This again called on the ANC’s supporters on the ground to organise themselves into small underground units and acquire weapons by hook-or-by-crook. This was broadcast on Radio Freedom followed by the following call:

“Ambushes must be prepared for policemen and soldiers in the locations with the aim of capturing weapons from them. Our people must also manufacture home-made bombs and petrol bombs with material that can be locally obtained. In addition, our people must also buy weapons where possible. After arming themselves in this manner, our people must begin to identify collaborators and enemy agents and deal with them. Those collaborators who are serving in the community councils must be dealt with. Informers, policemen, special branch police and army personnel living and working amongst our people must be eliminated. The puppets in the tricameral parliament and the Bantustans must be destroyed.”[2]

With this statement the ANC had given the order to its supporters, on the ground, to go and attack individuals perceived to be enemies of the people, policemen and councillors being primary targets. Given the hold the banned and exiled ANC exercised over the imagination of radical young black South Africans, this was a rescindment of the Sixth Commandment handed down by The Gods. However, the ANC had been expelled from Mozambique in terms of the Nkomati Accord of the previous year and it had limited capacity to actually provide either weaponry to these self-organised units, or operational guidance on the ground, though several hundred ill-equipped MK cadres were infiltrated into South Africa at the time.

An extract of the leaflet version of “The future is within our grasp”, 25 April 1985

The intention was initially then that groups of activists would be organised into squads and provided with grenades – the munitions most easily smuggled into the country - which then could be used against targets. In response to this initiative, and the mob violence that had already been directed against policemen and other suspected collaborators, the Security Police formulated a counter plan to provide young activists with doctored grenades, with their timing devices set to zero.

The Askari tasked with carrying out this operation was Joe Mamasela who approached and recruited young Cosas activists in Duduza on the East Rand, claiming to be a member of MK. He provided youth with grenades (and a limpet mine) and instructed them in their use. When the activists sought to use them in an attack inter alia on the already burnt out (and vacated) houses of two suspected collaborators on the midnight of the 25 June 1985 the grenades exploded killing eight and injuring seven.

There were two consequences of this atrocity. The first, as Howard Barrell later noted, was that “township comrades now had caused to be deeply suspicious of anyone offering them arms. The incident received widespread publicity and meant the end of the grenade squad idea.” The second was that it would unleash the phenomenon of “necklacing” into the public consciousness. The mass funeral of the “Cosas 8” was held on the 20 July 1985. At the funeral Maki Skosana, who was suspected of being the girlfriend of Mamasela, was necklaced for being an impimpi in full view of the television cameras. Her killing - in which she was kicked, stoned and then set on fire by the crowd - was filmed in full and broadcast on SABC news that night, as well as internationally. Subsequently this was often described as the first necklacing.

In reality this had in fact occurred a few months earlier, two days after the police massacre of funeral goers on 21 March 1985 in Langa township, Uitenhage, in which over twenty people were shot dead by police. As the journalist Jon Qwelane recalled two years later, a crowd then sought retribution by going after anyone connected with the system. Their first target was Mr Thamsanqa Kinikini, a successful businessman who was the only remaining member of the kwaNobuhle Community Council, having rebuffed pressure to resign along with the others several days before.

He and his two sons, aged 21 and 13, as well as two nephews, had sought refuge in the mortuary he owned, which was soon surrounded. The crowd was further enraged after shots were fired at them, and they proceed to set the building on fire. When Kinikini’s older son and two nephews sought to escape they were captured, butchered with whatever crude implements were at hand, and then set alight. With no way out of the burning building Kinikini shot his young son, before they were both completely incinerated. The crowd then turned on two men who worked for another wealthy and unpopular businessmen in the township. “The man’s two employees were beaten up by the mob. Then tyres were placed on them, soaked with petrol and set alight,” Qwelane wrote. “The ‘necklace’ executions had begun.”

Throughout the second half of 1985 Radio Freedom continued to call for attacks on alleged collaborators, intertwined with calls for the People’s War to be extended to the white areas of the country. A broadcast on 22 July 1985 in response to President PW Botha’s declaration of a state of emergency stated “Let us intensify the elimination of all collaborators from our nation. The whole country must go up in flames.” In a broadcast in response to the assassination by state agents of Victoria Mxenge Radio Freedom commented in early August: “Let us hit at his puppets and agents. Let us attack relatively small police and army units when possible. Let us spread this people's war to the white suburbs… While we continue eliminating enemy agents inside within our community, let us also spread the campaign into the white, Indian and Coloured residential areas. The whole country must go up in flames.”[3]

In an address to the nation on 6th August 1985 Oliver Tambo said that a good deal of progress had been made in making the country ungovernable. “Correctly, we concentrated on the weakest link in the apartheid chain of command and control. For months we have maintained an uninterrupted offensive against the puppet local government authorities in the black urban areas as well as other state personnel in the townships such as the police and their agents.” In an address on Radio Freedom later that month Thabo Mbeki himself stated that if the black people who served the regime as soldiers, policemen, community councillors, bantustan leaders, and civil servants refused to “come over to the side of the people” they would end up being buried as “traitors.”

On the 6th of September Radio Freedom broadcast a call for the killing of white policemen and soldiers in their own homes. “What we are doing against their black colleagues in other areas must be done against white police and soldiers also. All must be attacked whether they are in uniform or not. After all, a soldier or a policeman does not change his evil heart when he takes off his uniform.” In early October this message was repeated: “We must attack them at their homes and holiday resorts just as we have been attacking black boot-lickers at their homes. This must now happen to their white colleagues. All along it has only been black mothers who have been mourning. Now the time has come that all of us must mourn. White families must also wear black costumes.”[4]

A discussion article in the November 1985 edition of Sechaba by Cassius Mandla praised the use of petrol-based terror against black sell-outs in the townships. It stated:

“It is interesting to imagine how it feels to live and move around there, in liberated townships in which maintaining order means turning them into undeclared operational areas. Here collaborators and informers live in fear of petrol, either as petrol bombs being hurled at their homes and reducing them to rack and ruin, or as petrol dousing their treacherous bodies which are set alight and burned to a charred and despicable mess. No longer is it just lucrative and safe to commit unspeakable acts of treachery against the people; selling out under cover of innocences, and life being all beer and skittles. Lucrative it still is to sell out, but it carries the immediate hazard of having one’s flesh and bones being reduced to unidentifiable ashes.”

A broadcast by Radio Freedom in December explicitly mentioned the use of the necklace method. It stated that the military attacks of MK cadres “are a continuation of petrol bomb attacks, the necklaces against the sell-outs and puppets in the townships, the grenade and stone-throwing attacks that are being carried out daily by oppressed workers and youths in the [unclear] of our townships against the heavily armed troops and police.”[5]

In October 1985 the police reported that since the unrest began 12 policemen had been killed in mob violence and another 700 injured. The homes of 500 policemen had been attacked and 400 of these destroyed by fire. Thousands of other homes had been gutted in arson attacks. The weapons that had been used in these attacks included grenades, firearms, and acid and petrol bombs. “Petrol bomb attacks on homes have caused numerous deaths by burning, including children trapped inside the burning dwellings,” the police noted. A spokesman was quoted as saying that the intimidatory effect of burning suspected informers and collaborators alive in public had been “awesome”.[6] The following year the South African Institute of Race Relations estimated that there had been 879 people killed in political violence in 1985, of whom 441 were killed by the security forces, and at least 280 by “other civilians”. 26 members of the SAP and SADF had been killed in the unrest.[7]

1986: The “year of the necklace”

In its January 8th statement of 1986 the ANC NEC noted that significant strides had been taken of transforming armed confrontation with the regime into a People’s War. It praised the “mass combat units” - formed to destroy the organs of government and to make the country ungovernable - for the disciplined and courageous manner in which they had carried out their tasks. It referred too approvingly of the measures taken to “maintain revolutionary law and order in various localities throughout the country.” It now called for an expansion of the revolutionary violence in the country:

“To retain the strategic initiative, apart from confronting the army of occupation in our areas, it is essential that we carry and extend our offensive beyond our township borders into other areas with even greater determination….The charge we give to Umkhonto we Sizwe and to the masses of our people is attack, advance, give the enemy no quarter--an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth!”

This call for “no quarter to be given” was repeatedly broadcast throughout the year. The first part of 1986 saw a leap in the number of deaths in political unrest. Most of these were the result of attacks by ANC supporters on their enemies within the black community, rather than security force action. The government would claim that 265 black people were killed by “black radicals” in the first five months of the year, as against 161 killed by the security forces.

In a Radio Freedom broadcast on 13 March 1986 the ANC boasted of how “We have managed to weaken the enemy using rudimentary weapons of war. With the usage of Molotov cocktails and necklaces, stones and knives, we have managed to drive the enemy to the extent where he has to impose a state of martial law; and despite that martial law we have continued and maintained the momentum of struggle.”[8] However, despite the repeated promises by the ANC on Radio Freedom to get modern weapons of war into the hands of the masses, they had largely failed to do so.

On the 13th April 1986 Winnie Mandela made her notorious comment to an audience in the Krugersdorp township of Munsieville that: “We have no guns – we have only stones, boxes of matches and petrol. Together, hand in hand, with our boxes of matches and our necklaces we shall liberate this country.” These remarks were not that different to the message that had been broadcast by Radio Freedom to the party’s activists on the ground the month before. In this case however there were foreign journalists in attendance and Winnie Mandela’s remarks were filmed and then broadcast abroad.

They were only then reported on in the local press where they caused an outcry. Mandela first claimed she had been misquoted, and then that they had been taken out of context and misunderstood. In the minutes he kept of Winnie Mandela’s subsequent visit to Nelson Mandela at Pollsmoor Prison the family’s lawyer Ismail Ayob noted, “NM approved of WM’s necklace speech. He said that it was a good thing as there has not been one black person who has attacked WM. He however had some reservations on WM’s attack on Rex Gibson of the Star because Gibson had published a powerful defence on the speech a few days earlier.”

In a broadcast on 5th June 1986 on behalf of the ANC NEC Oliver Tambo noted that “On 8th January 1986, we called upon the nation to attack, advance and give the enemy no quarter. These calls have been answered with increasing and dramatic vigour.” The instruction issued by the ANC NEC was to move from ungovernability to “people’s power” Tambo stated: “People's committees, street committees and comrades' committees are emerging on a growing scale as popular organs in the face of the collapse of the racist stooge administration. People's courts, people's defence militia and other popular organs of justice are, in many cases, challenging the legitimacy of the racist machinery of so-called justice [system of the] forces of repression.”

Mid-1986 was the high point of the insurrection. Following the imposition of the state of emergency on 12 June 1986 (some 25 000 suspected pro-ANC activists would be detained) the state’s security forces were able to steadily bring the security situation under control. According to SAIRR estimates 1 298 people died in political violence during 1986. In a reversal of the proportions from the 1985 about half these deaths could be attributed to “conflict within black communities”, and a third to security force action. The remainder were attributable to other types of violence (such as insurgency incidents) or where the circumstances were unclear. The predominant means by which ANC militants had sought to eliminate their opponents in 1986 was by burning them to death.

It was estimated that 479 people had been killed in this manner in 1986, 307 by means of the necklace. (Thirty seven suspected witches were also necklaced or burnt to death during the year.) 220 of these necklacings had occurred in the first half of the year, and only 87 necklacings in the second half. Through the whole of 1987 only 19 incidents of necklacings were recorded.[9] In May 1986, one government report stated, 157 black South Africans had been killed in unrest related incidents, well over half by “black radicals”. In May 1987 the total number had been reduced to eight.

1987: The necklace is abandoned

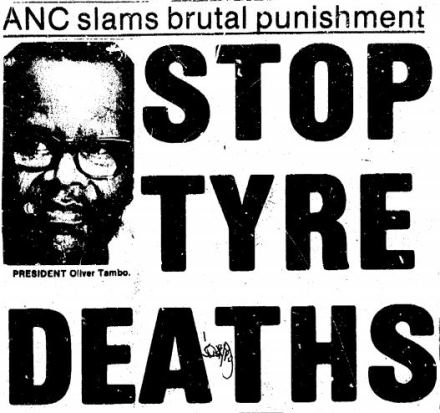

With their hopes of the immediate violent overthrow of the regime having drastically receded, the ANC leadership now pivoted towards political efforts and a diplomatic push in the West. The failure of ANC leaders to unequivocally condemn the necklace-method was a major obstacle to the success of these efforts, particularly in America. The PW Botha government had also made ANC support for necklacing, by Winnie Mandela and others, central to its counter-propaganda against the ANC.

The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 enacted by the United States Congress, though a huge aid to the ANC’s goal of crippling the South African economy, described necklacing as “abhorrent” and called on the ANC to “strongly condemn and take effective actions against the execution by fire, commonly known as ‘necklacing’, of any person in any country.” To give effect to this demand the Act prohibited the extension of any assistance to “any individual, group, organisation, or member thereof, or entity that directly or indirectly engages in, advocates, supports, or approves [this] practice.”

Although the ANC leadership initially responded indignantly to such demands it reluctantly came to accept the need to disassociate itself from necklace murders. This decision was conveyed by the ANC NEC to members of the UDF / ANC underground within South Africa at a closed meeting held during the International Conference on the Plight of Children Under Apartheid in Harare in late September 1987. The message from Oliver Tambo to delegates, the Weekly Mail reported, was that “the necklace as a form of punishment should stop. It has rightly or wrongly served its purpose and there is no way that people should continue with it.”

The front page headline of the Sowetan, 28 September 1987

The ANC and the necklace

It is clear from this history that the ANC leadership had used Radio Freedom broadcasts to systematically incite their supporters in South Africa to kill alleged collaborators in the black community from early 1985 onwards. The necklace however was not dreamt up in Lusaka but was rather an invention of the liberation movement’s followers on the ground in South Africa. Nonetheless it served the purposes of the ANC at the time very effectively, especially given the failure of MK to get meaningful quantities of modern weaponry into the hands of the “young lions” on the ground.

Any committed ANC activist in the townships who listened to Radio Freedom between 1985 and 1986 would have regarded the necklacing of opponents as completely consistent with the exhortations of ANC leaders to eliminate the movement’s enemies with whatever weapons were at hand, and make the country go up in flames, Such actions were also regarded by MK leaders as completely in line with the movement’s objectives in making the country “ungovernable”. For such leaders the necklace was, in Robespierrean terms, “speedy, severe and inflexible justice”, an emanation of popular virtue.

In an interview with Sechaba (May 1986) on the “People’s War” Ronnie Kasrils commented that: “We’ve seen them [the People] attacking the community councillors and the informers – and here they’ve had to resort to rough justice, for the state relies on its loathsome army of sell-outs and informers, and, unless a people arisen can purge its community of the enemy within, it is not possible to advance.”

In the September 1986 issue of Sechaba Mzala (Jabulani Nxumalo) wrote:

“Let the racist magistrates and lawyers shout their lungs out in scorn of the 'necklace' method of punishing collaborators, let them call the people's courts "kangaroo courts" if they want to, but we shall always reply to them by saying: When we say power to the people, we also mean the right to suppress the enemies of the people, we also mean the country's administration and control by the ordinary people. We shall not suddenly be anarchists simply because we refuse to abide by the conventional legal norms generally associated with courts of law in South Africa.”

In the December 1986 edition of Sechaba MK Commissar Chris Hani described the use of the necklace against alleged puppets and collaborators as being entirely in line with the objectives of the People’s War. As he put it:

“Because the Black policeman, the Black special branch and the Black agent stay in the same township as we are, have been the conduit through which information about our activities, about our plans has been passed to the enemy. This has made the process of organisation and mobilisation very difficult. So the necklace was a weapon devised by the oppressed themselves to remove this cancer from our society, the cancer of collaboration of the puppets. It is not a weapon of the ANC. It is a weapon of the masses themselves to cleanse the townships from the very disruptive and even lethal activities of the puppets and collaborators. We do understand our people when they use the necklace because it is an attempt to render our townships, to render our areas and country ungovernable, to make the enemy's access to information very difficult.”[10]

It is difficult to see how the ANC leadership could have admonished its supporters to cease using the necklace in the critical 1985 to 1986 period. It was by far the most effective form of revolutionary violence at their disposal – largely because it was such an awe-inspiring instrument of terror and intimidation.

It led, temporarily at least, to information from the state’s informer network in the townships drying up, which was critical to the survival of MK operatives being infiltrated into the country, and helped drive the mass resignations of councillors. After a while all a “young lion” needed to do to get his point across was shake a box of matches outside the house of a potential target. The alternative forms of revolutionary violence used at the time were also horrific.

These mainly involved petrol bomb or grenade attacks on the homes and families of alleged “collaborators”, in which the victims (including children) were often burnt alive or mutilated and disfigured. As one contributor to the African Communist noted in 1987:

“Because it is political, revolutionary violence seeks to destroy apartheid by cementing a popular alliance of the widest possible character: hence it is a violence which is controlled and discriminate and its inspiration remains humanist throughout. But this violence cannot help to cement popular unity and destroy apartheid unless it is also effective. We cannot denounce this form or that form of violence (the US Anti-Apartheid Act is particularly obsessed with the 'necklace' killings), however gruesome or unpleasant it might be, simply because it offends those whose whole way of life inclines them to a hypocritical disregard for the realities of oppression.”

To sum up then, Winnie Mandela’s necklacing remarks in April 1986 were completely consistent with the ANC policy and objectives of the time. She said little in that speech which had not already been broadcast on Radio Freedom before. If she committed any misdemeanour it was in putting that message out on the wrong frequency, the one that reached the white and Western audience, thereby causing a public relations debacle for the ANC. If this is the case how did the myth arise that her remarks were a complete outlier as far as the ANC was concerned?

One reason is simply that her comments were a source of huge controversy at the time, and they linked her indelibly in the Western imagination with this brutal practice. The other was that after the ANC had formally distanced itself from necklacing in September 1987, it became progressively more inconvenient to acknowledge its responsibility for this formerly useful form of revolutionary violence.

By 1992 the ANC was claiming that necklacing was a “a barbaric and unacceptable method of execution which the ANC has never condoned.” After coming to power in 1994 the ANC simply denied that it had incited its supporters in the mid-1980s to use “extreme methods” against the enemy within. Such post-facto denials were then repeated in the secondary literature. One of the most cited sources for the view that Winnie Mandela was speaking out of turn is Anthony Sampson’s authorised biography of Nelson Mandela, published in 1999. This describes the ANC’s response to Winnie Mandela’s necklacing speech as follows:

“The ANC felt ambivalent in the face of the government’s own violence, and Oliver Tambo was reluctant to criticise the speech publicly. ‘We are not happy with the necklace,’ he told a summit meeting of non-aligned nations in Harare, ‘but we will not condemn people who have been driven to adopt such extremes.’ Privately Tambo was appalled, and in London he asked Winnie’s neighbour and friend in Soweto Dr Motlana to shut her up… [Nelson] Mandela himself, as he told his lawyers George Bizos and Ismail Ayob, was shocked by any encouragement of necklacing, as were the other prisoners in Pollsmoor: ‘ We wanted ungovernability, but not necklacing’, said Kathrada.”

Sampson’s source for Tambo’s remarks is Emma Gilbey’s 1993 book, The Lady: Life and Times of Winnie Mandela. In turn, Gilbey’s source is a Weekly Mail article from 11 September 1986, so four months after the Munsieville speech. These and other similar equivocations were broadcast on the frequency intended for Western and white South African consumption. In real terms they were quite meaningless.

Indeed, only a few days later the ANC Secretary General Alfred Nzo let the cat out of the bag again when he was quoted in the London Sunday Times as saying that “collaborators with the enemy” had to be eliminated. When asked if this included necklacing Nzo replied, “Whatever the people decide to use to eliminate those enemy elements is their decision. If they decide to use ‘necklacing’, we support it.'”[11]

Sampson’s source for the claim that Tambo was privately appalled and told Winnie to desist is given as “private information” in the footnotes, and so is uncheckable. The sources meanwhile for the claim that Nelson Mandela and the other political prisoners at Pollsmoor were “appalled” is given as interviews with Ayob and Ahmed Kathrada in 1997 and 1998, over ten years after the fact. These claims clearly stand at odds with the hard documentary evidence contained in Ayob’s contemporaneous notes mentioned above. These were actually in Sampson’s possession, having been dug out of the archives by his formidably able researcher, James Sanders. The Mandela camp however reportedly threatened to withdraw their co-operation if Sampson even mentioned this document in the book, and so he pulled it.

As the late David Beresford observed in his posthumously published obituary of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, had Nelson Mandela acknowledged that he had, in fact, approved her remarks at the time (or she had disclosed this) it would have taken much of the heat off her, given “his virtually unchallengeable reputation.” Instead, she was left to bear history’s opprobrium alone.

Updated with additional information 11 June 2018

[1] This has received less attention in the South African media, one exception being John Kane Berman’s article on Politicsweb here.

[2] A repeat broadcast of the ANC NEC statement was aired on Radio Freedom 6th May 1985

[3] Radio Freedom 2 August 1985

[4] Radio Freedom 7 October 1985

[5] Radio Freedom, 17 December 1985

[6] Citizen 4 October 1985

[7] SAIRR, 1985 Survey of Race Relations in South Africa.

[8] Radio Freedom 13 March 1986

[9] South African Institute of Race Relations, 1986 Survey of Race Relations.

[10] Sechaba magazine, December 1986. Hani did introduce a certain note of caution stating, “But we are saying here our people must be careful, in the sense that the enemy would employ provocateurs to use the necklace, even against activists. We have our own revolutionary methods of dealing with collaborators, the methods of the ANC. But I refuse to condemn our people when they mete out their own traditional forms of justice to those who collaborate. I understand their anger. Why should they be cool as icebergs, when they are being killed every day?”

[11] Sunday Times (London) 14 September 1986, quoted in SAIRR Race Relations Survey 1986.