Up until shortly before the 1st November 2021 local government elections it appeared that the African National Congress would continue getting away with it appalling record in government. It seemed probable that despite significant underlying discontent the ruling party would win a similar share of the vote as it had done in 2016. Yet something seems to have given, in the final stages of the campaign, and for the first time ever the ANC’s support fell well below fifty percent of the vote nationally.

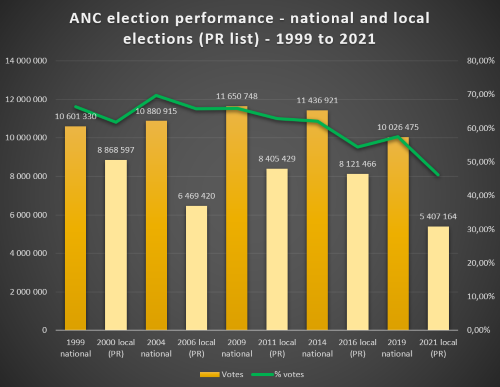

As Pierre du Toit has noted the mass of newly liberated citizens formed a “historic block” of loyal voters post-1994. In national elections since 1999 this block of over ten million voters have returned the ANC to power with super-majorities which have only slowly been eroded, despite two significant splinters. In the local government elections, where turnout is lower, over eight million voters generally turned out for the ANC. The ANC’s overall margin of victory was really determined by how effectively the opposition parties were able to turn out their supporters.

In this local government election however, the ANC secured only 5,4 million votes on the PR list, down 2,7 million from the 8,1 million it won in 2016. The ANC’s overall share of the PR list vote fell to 46,1%, down from 54,5% in 2016. The percentage result would have been worse for the ANC were it not for the Democratic Alliance’s equally dismal failure to hold onto, and turn out, its own traditional support base.

In the 2019 elections just under half (44%) of the ANC’s national support came the two provinces of Gauteng and KwaZulu Natal. In these latest elections, the ANC’s PR votes in these two provinces declined by 677,504 (-41%) and 837 805 votes (-44%), respectively, from what the party received in 2016.

|

2016 local (PR) |

2021 local (PR) |

Change |

||||

|

|

Votes |

% |

Votes |

% |

Votes |

Percentage point |

|

Eastern Cape |

1 206 761 |

65,9% |

941 250 |

64,0% |

-265 511 |

-1,9% |

|

Free State |

498 700 |

61,9% |

321 949 |

51,3% |

-176 751 |

-10,6% |

|

Gauteng |

1 634 833 |

46,1% |

957 329 |

36,0% |

-677 504 |

-10,1% |

|

KwaZulu-Natal |

1 906 159 |

59,0% |

1 068 354 |

41,8% |

-837 805 |

-17,2% |

|

Limpopo |

875 262 |

69,4% |

785 960 |

70,3% |

-89 302 |

0,9% |

|

Mpumalanga |

749 554 |

71,0% |

478 888 |

60,6% |

-270 666 |

-10,5% |

|

North West |

525 685 |

59,3% |

382 705 |

56,1% |

-142 980 |

-3,2% |

|

Northern Cape |

218 248 |

58,7% |

165 140 |

51,0% |

-53 108 |

-7,7% |

|

Western Cape |

506 264 |

26,5% |

305589 |

20,5% |

-200 675 |

-6,0% |

|

Total |

8 121 466 |

54,5% |

5 407 164 |

46,1% |

-2 714 302 |

-8,3% |

It was really only in the Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga and Limpopo that the ANC retained the “overwhelming majorities” of old.

There is little left of the moral authority that the ANC once wielded. In polling conducted by Victory Research for News24 ahead of the elections respondents were asked to choose which of a number of words most applied to the three largest parties; the ANC, DA and EFF. 69.7% of respondents applied the label “corrupt” to the ANC, including 60.1% of the party’s own supporters.

Only 46,4% of survey respondents gave the ANC a favourable rating (56% among black Africans.) Gareth van Onselen, CEO of Victory Research, commented that “the ANC’s brand is fundamentally damaged”.

President Cyril Ramaphosa was assessed favourably by 55,6% of respondents (57,2% among black Africans), considerably higher than the ANC’s 47,4%. Equally significantly he was regarded favourably by 50,4% of minority respondents, compared to just 14,3% who had the same view of the ANC. This in contrast to Jacob Zuma who was, and is, viewed unfavourably by the great mass of minority voters.

Unlike with Jacob Zuma then, Ramaphosa’s leadership buoys up ANC support outside of KwaZulu Natal, as he is more popular than the party he leads. Probably more significantly, electorally speaking, his benign countenance denies the opposition a widely detested ruling party figurehead against whom they can effectively mobilise their supporters.

Yet Ramaphosa’s halting and indecisive leadership of party and state has harmed the ANC’s electoral prospects in more indirect ways. Unlike any of his ANC predecessors he has allowed efforts to go ahead to slowly clean up the state and state-owned-enterprises of corruption. This, and the Political Party Funding Act he signed into law earlier this year, has had the downside of starving the ANC’s patronage-driven political machine of resources.

Yet his concomitant failure to get a grip on the ANC politically and drive through meaningful reform - or even just abandon its most radioactive late Zupta-era policies (like Expropriation Without Compensation) – has denied his government any upside in the form of economic growth, with the growing employment and tax revenues that come with it.

The loss of sole majority control over almost all but two metros, as well as dozens of local government municipalities will further curtail the resources the ANC patrons are able to distribute to their clients. Moreover, the collapse of basic service delivery in many urban areas is clearly starting to outweigh the benefits of ANC state patronage as the primary consideration among voters.

A significant section of the ANC’s support base vote for it not so much out of personal loyalty but because it is seen as the “party in power”. Such support may appear solid on the surface, but it quickly dissipates once power starts slipping from the ruling party’s grasp.

The ANC’s fall below 50% nationally in this election may also have a psychological effect in itself. Single-party dominance is sustained, in part, by the perception of dominance, and the expectation that it will continue into the foreseeable future. This has the effect of curbing political and civil society counter-mobilisation against the ruling party as this is seen as ultimately futile.

The French political scientist Maurice Duverger put it this way: “Domination is a question of influence rather than of strength: it is also linked with belief. A dominant party is that which public opinion believes to be dominant…. Even the enemies of the dominant party, even citizens who refuse to give it their vote, acknowledge its superior status and its influence; they deplore it but admit it.”

What has been shattered in this election then is the expectation that the ANC will “govern until Jesus comes back”. This is likely to further strengthen democratic contestation going into 2024.

From a reformist’s perspective the problem now is the degree to which ANC dominance continues to live on outside of the party itself; in a judiciary increasingly dominated by Comrade Judges, an English-language media and academia that remains ideologically committed to transformationism, and in offshoot parties (such as the EFF and Patriotic Alliance) which have adopted its racial ideology and/or its corrupt, patronage-based mode of operation.