An open letter to Minister of Health Aaron Motsoaledi on the high cost of healthcare and the elephant in the room

Dear Minister Motsoalodi,

In the turmoil over the proposed National Health Insurance, you and others have had much to say about the high costs of private healthcare, at the same time acknowledging that South Africa has one of the top five private healthcare systems in the world. And, yes, our public healthcare is in a shambles. It is a pitiful situation that needs correcting. In all this bluster however, doctors, and specialists especially, are singled out for blame as being the chief culprits for high costs in private healthcare.

But Minister, for all your good intentions and noble ambitions, when apportioning blame you have not taken a close enough look at the elephant in the room. You may have caught a fleeting glance of it, but for all your pronouncements we could be forgiven for thinking that you have not really seen it at all.

You will know that in the 1960s medical aids were formed by large companies with many employees (like mining houses) to buy bulk discounts for prompt, private medical care for their staff and family members. Private doctors agreed to work for a discounted rate in return for a steady flow of patients without the worry of having to claim payment directly from the members themselves, creating in effect a ‘cradle to the grave' arrangement of open access to both care and funding that initially served both parties well. But medical inflation (about 14%) was far higher than expected, and increasing technologies and life expectancies drove the costs of providing care higher than anyone, particularly the medical aids, anticipated.

Before long members saw their medical benefits limited, had to get preauthorisation for treatments and medications, and the free relationship between doctors and patients disappeared due to the third intermediary who in effect controlled the purse strings. The publishing of an ‘agreed' tariff by the medical aids - the old medical aid rate and later known as the RPL (Reference Price List) - also created an impression that this was the ‘going rate' or the ‘acceptable rate' whereas in fact it had never been anything of the sort. It was a rate based on earlier agreements at the initiation of the doctor-funder relationship that had now fallen away.

Doctors who wanted to continue the old cosy relationship with medical aids had three choices - work longer hours, charge higher rates and risk losing patients, or increase the amount of work done on each patient. An economic fundamental fell into place - that if ones business has limited mark ups, the volumes have to increase substantially to make it profitable.

Doctors who saw more patients had to shorten consultation times in order to retain some semblance of a normal afterhour's life, and patients saw the difference in being ‘pushed through' a system that was as much about numbers and turnover as about quality of care. In a pressured consultation environment it is much easier for a doctor to ask for a test to confirm absence or presence of a disease than it is to take the time and effort by talking and careful examination to exclude it.

For doctors doing procedures, the easiest, but highly unethical, way to stay in business was to increase the number of tests and procedures on their patients. In 2000, in a sweeping statement that was never seriously contested, Medscheme estimated that as much as 40% of private medical aid expenditure was unnecessary, with pure fraud making up about a third of that amount.

In the midst of this turmoil ethical doctors avoided the perverse environment of over servicing by charging appropriate fees higher than those that the medical aids had established. The so called ‘private rate' had in fact an upper limit of about three times the ‘medical aid rate' which in those days was set by the South African Medical Association (SAMA), and most doctors' fees were somewhere between this upper limit and the medical aid rate.

Patient consumers were caught in the middle, paying high medical aid premiums, but also top up fees to their doctors. Their anger was directed initially at the medical aids, many of whom promised 100% cover without making sure that their members understood that 100% was exactly that of the medical aids' own rates, not the doctors'.

Some medical aid call centres responded to angry members by turning the anger back towards their own service providers with comments like "Your doctor's overcharging." Medical aids like Discovery began ‘incentives' (although one could be forgiven for thinking of them as blackmail tactics) to draw doctors into line, promising to pay doctors directly for work if their rates were lowered to their own Discovery levels, even if the patient's plan covered the doctor's fees in full.

Anything above that and the whole sum would be paid directly to the patient, despite the cost and administrative burden that that entailed. Many a doctor has seen the results of his or her hard earned efforts spent on new mag wheels for a car or to settle an overdraft.

Around 2006/2007 the Dept of Health asked for a series of practice cost studies among all medical groups to ascertain the ‘real' value of a doctor's services. These studies were done by actuaries over the next two years contracted by the doctor group representatives themselves at great expense, and the results showed to the Dept of Health's dismay that the true values of doctors' services were very close to the upper limits established by SAMA some years previously.

The old ‘medical aid rates' were simply not viable for an ethical medical practice. Not getting the results they wanted or expected the Department of Health did the obvious thing. They ignored the studies and took no action on the results.

In the results of a case brought by SAPPF and others, acting Judge Ebersohn on 28th July 2010 declared the (‘medical aid rate') RPL 2007 - RPL 2009 null and void. He found the process by which the RPL and rates were determined to be unfair, unlawful, unreasonable and irrational.

The Judge also said that the process resulted in tariffs that were "unreasonably low " and one of the reasons cited for the exodus of doctors from South Africa. Unfortunately all Schemes and Administrators still utilise the now "illegal" RPL structures to set their benefits and tariff structures, in doing so disregarding an order of the High Court.

The Competition Commission declared around the same time that publishing any declared ‘rate' for medical services constituted price fixing and was illegal. Medical aids could publish their own rates in terms of payment benefits.

Medical aids came up with the idea of establishing ‘designated service providers' (DSP's) - lists of doctors to whom their members could go for medical treatment and who would be paid better than the lowest rate for their services - especially for members on lower value medical plans. This list included preferred hospital groups.

Members of lower plans no longer had free choice as to which doctors they could see or where they would receive treatment, creating situations where some would have to leave their own towns where services exist to go to neighbouring towns for treatment. In no way was this system implemented looking at the quality of available medical services, only a willingness by the doctor to be controlled by the funder in order to gain patients.

Quality of care did not come into it. For example, the Life private hospital in Knysna, being the only one in the area at that stage, was initially on the list. Insurance brokers saw the opportunity to put retired pensioners and high income earners onto the DSP associated medical insurance plans which were much cheaper.

Discovery saw the trend away from the more expensive plans in the Knysna region, saw the impact on their incomes, and without explanation removed the Knysna Private Hospital from the list, inconveniencing all their own members in the process, and the doctors who had already built up relationships with them.

The startling thing about the medical aids' infrastructure is this: they know everything there is to know about doctors' individual diagnosis, testing, operating and prescribing habits. No patient account is accepted without billing and diagnosis codes. Over time the medical aids have built up a collaborative database of doctor profiles, so that exceptions stick out.

They know who the good doctors and the bad doctors are by looking at the standard deviations of countless different variables. But acknowledging quality is seemingly not as important as having control.

As a doctor, sign a DSP agreement, tying you into a stringent fee structure, and you will be added to the list. Very few doctors are challenged for being outside the norms according to the medical aids' own statistics, and the reason may be that business as it is for the major players does not warrant the effort or recrimination.

Instead of acknowledging the true values of doctors' services, the medical aids have tried increasingly to contain costs by limiting their own members' access to medications and procedures. So the list of allowed drug formularies, use of generic medications, requests for motivations before surgical procedures, allowed and disallowed operations has grown over the years to become an added administrative burden on both doctors and patients.

In doing so many medical aids blatantly disregard the rulings of the Council for Medical Schemes, their own ruling organisation, and the ethics of the Health Professions Council, in saying authorisation for medical and surgical intervention may not be refused unless there has been contact between an equally qualified doctor from the medical aid and the doctor looking after the patient beforehand. This is just not done.

Instead, burdensome motivation letters have become a norm, requests for unnecessary and expensive investigations beforehand (e.g. requesting a CT scan before a septoplasty - a blatantly ridiculous request) to make ‘sure' the operation is justified. Against the backlash, the medical aids themselves say that they are not refusing care to their members. Instead, "Go ahead and have the operation by all means. We're just not going to pay for it."

So how have the major medical aids been doing?

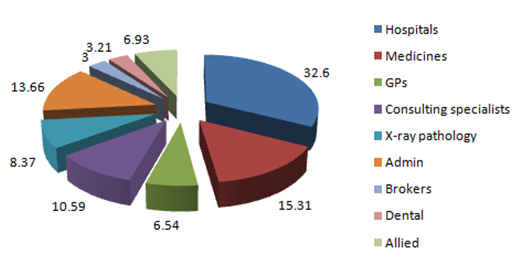

Total expenditure from medical aid premiums 2011 - % by category

This pie graph represents the total income into the pool of money paid into medical schemes, and the percentage payout to different parts of the industry and can be applied to a medical aid like Discovery. Note that GPs earn only 6.54% of the total, consulting specialists (physicians, surgeons, anaesthetists etc.) 10.59%, and that administration by the medical aid consumes 13.66 % of the total - marginally less than all consulting doctors combined.

The first years of medical aids saw this percentage as a reasonable 5% acceptable to everyone, doctors included. GEMS, the medical aid catering for governmental employees, and which is privately administered, still manages to keep its administrative burden to 6% - suggesting that all medical aids should be able to do.

Digging deeper into these figures, for a medical aid like Discovery, the similarity in size of the slices for consulting doctors combined (17.13%) vs. administration (13.66%) is alarming because of the contrasting size of the work force required to keep either operational. By my estimation there are 15000 consulting doctors in South Africa, paying an estimated 20000 additional salaries in perhaps 10 000 independent practices, a work force of 35000 in total.

Contrast Discovery Holdings, administrators of Discovery Medical Aid (and effectively the same people involved in both) with a staff of 5000, not all of whom are involved in the medical aid administration. Taking Discovery's market share into consideration, simple calculations show it costs at least twice per employee per year for Discovery to administer their own medical aid than it costs for doctors and their staff inclusive to provide the medical service itself.

I'll say that again in another way to be sure the message sinks in. It costs Discovery twice as much on average per employee to collect claims data and to enter it into a software system, to run the system and have managerial oversight and strategic planning over the infrastructure, as it does for doctors to see patients in their rooms, diagnose them, take them to theatre for long or short surgical procedures, day, night, public holidays and weekends, look after them in the hospital, and follow them up, and for the doctor's staff to do the same administration of the practice. The nature of the work itself, to be perfectly frank, is just not equitable.

I fail to see how any administration can justify these figures except as being either inefficient, or overly generous both in their own salaries and dividends to shareholders. What happened to administrative efficiency and economy of scale? It appears that the modern medical aid has not achieved anything better over forty years other than diverting a larger portion of members' own contributions into their own pockets.

Discovery Holdings - administrators of Discovery Medical Aid and many others - will argue that they as administrators only protect the interests of the medical aid members. Yet the 13.66% (and more than 20% in lower plans) that they claim for doing so is taken off the top of the medical aid income - what is left is only then available for allocating services to their members.

In other words, it is an absolutely risk free business model. Why would Discovery bother changing it? For the record, Discovery Holdings recorded an operating profit of nearly R3 billion in 2011, in the midst of a recession.

In summary, the roots of the present high costs of healthcare are not just based on the economic realities of inflation and technological advance. They lie instead in a broken and flawed relationship between doctors and funders that goes back over forty years. In this time the power of the medical aids has increased, and as holders of the purse strings, attempts to draw doctors into line based on limitation of costs and control have led to a backlash of over servicing and further expenditure, leaving patients more and more out of pocket, not to mention the cost to the economy, and to the morale of doctors who have not bought into this manipulative practice, and whom you place directly in the line of fire.

My vision, albeit optimistic, for the future would include a system whereby high quality and ethical doctors are treated as such and remunerated properly for their services, without having to consider manipulative business practices by medical aids. The membership of such groups should be on a peer-reviewed basis and according to recognised standards of practice.

The medical aids already have the data to support the claims of those who wish to be part of that group. The technology exists to make this possible. It need not be enforced on doctors, but I cannot imagine a doctor not wanting to raise his professional standing and earning potential in an ethical manner.

So, Minister Motsoalodi, our public health system is admittedly broken. Our private health system is effective though expensive. Doctors as a body have made historic mistakes that have left us in many ways vulnerable, or worse, subservient to the successful profit motives of big business personified by medical aid administrators.

The big business ambitions, wastage and desire for control of the industry of the medical aid administrators are the elephants in the room, Mr. Minister. Ignore them, or focus undue and unwarranted attention on the doctors you have left, and you will see South Africa get the universal healthcare system your efforts and policy deserve, and not the one the whole of South Africa craves.

Yours sincerely

Dr Martin Young

MBChB, FCS(Otol)SA

Click here to sign up to receive our free daily headline email newsletter