Election 2024: What would happen if Rise Mzansi, the PA, BOSA and ASA achieved their election goals?

24 January 2024

Rise Mzansi (RM), led by Songezo Zibi, the Patriotic Alliance, led by Gayton McKenzie, Build One South Africa (BOSA), led by Mmusi Maimane and Action South Africa, led by Herman Mashaba, will all be contesting national and provincial elections for the first time in 2024.

Each party has been relatively explicit when it comes to how they expect to perform. But before we set those expectations out, and see what their implications are, let us provide some context.

Many new political parties typically enjoy much media hype before an election. They have no real record, so no negative or comparative history of any sort, and offer some ostensible “new hope” in an often-depressing environment. They are also typically one-man – or one-woman – shows, and rely on a single charismatic leader, who is deemed newsworthy in and of themselves.

On the back of this, they enjoy disproportionately positive coverage, and no one really questions their policies or intent, or vets those leaders. As a result, they can promise the world, without serious cross examination.

Perhaps because of this these parties tend to predict extraordinarily good results, buoyed by the media affirmation; although there is also some strategic advantage to pretending you are bigger than you are – voters like “big”.

The Independent Democrats, led by Patricia de Lille, are a good example. Before the 2004 election they absolutely dominated the mainstream media, with endless uncritical interviews and profiles.

On the back of this, de Lille predicted, among other things, “10% to 12%” nationally and 5% in KwaZulu-Natal. On the day, she ended up with 1.7% nationally and 0.5% in KwaZulu-Natal.

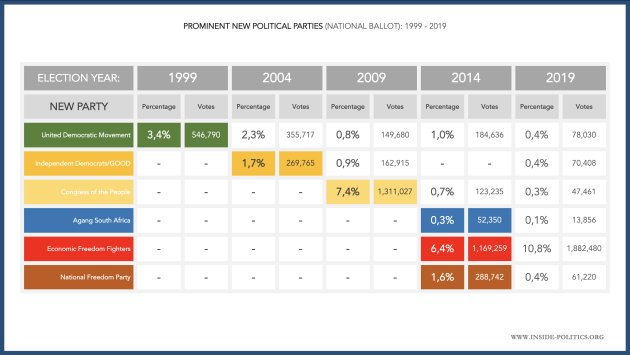

Below is a table that sets out the performance off all such “prominent” new parties on the national ballot, in each election since 1999.

Aside from COPE in 2009 (7.4% or 1.3m votes) and the EFF in 2014 (6.4% or 1.1m) – both breakaways from the ANC, which took with them much in terms of political and human infrastructure – the rest fare poorly (and then fade away); despite the pre-election hype.

The truth is: it is incredibly hard to make a big impact on the electorate starting from scratch. It is not just a crowded space but parties like the ANC, DA and EFF have a hard lock on their core support base. There is fluidity on the margins, and slightly more so with the ANC, but there is no great gaping chasm.

The truth is: it is incredibly hard to make a big impact on the electorate starting from scratch. It is not just a crowded space but parties like the ANC, DA and EFF have a hard lock on their core support base. There is fluidity on the margins, and slightly more so with the ANC, but there is no great gaping chasm.

RM, the PA, BOSA and ASA have all claimed, at various points, one of their core targets are alienated voters who have opted out. That is perhaps a gaping chasm, but there is a way to sample the theory that these parties will bring those voters back into the fray.

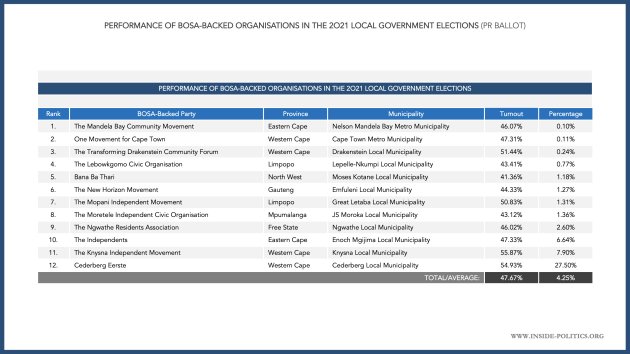

Below is a table of every municipality where BOSA-backed candidates stood in the 2021 local government elections.

Not only were the results abysmal, but turnout was dire. If that is any indication of the impact the BOSA “reinvigoration” message has, it simply doesn’t seem to result in a change in disenchanted voter behaviour. So, it is most likely, if these parties are to win votes, they will mostly come from existing parties.

These are all things to bear in mind. Let us turn to RM’s, the PA’s, BOSA’s and ASA’s predictions for 2024.

Rise Mzansi’s Songezo Zibi has said of his party’s upcoming performance, he expects: “Conservatively, between five and six percent, and that’s basically the minimum.”

According to TimesLive, the Patriotic Alliance has a strategy to get “1.5-million votes” which will make the party the “kingmaker”

Build One South Africa’s Mmusi Maimane says: “We are going for 2 million votes”

Action SA’s Herman Mashaba has said, “Watching the developments, ActionSA is not only going to emerge as the second-biggest party [in] 2024, it is going to emerge as the biggest party in South Africa.” The latter is more fanciful than the former (and the former is pretty fanciful already), as ever with Mashaba.

But the former has also been echoed by ASA party chairman Michael Beaumont, who has said, “What we are seeing is that there is very steady progress that is going to put us in a position where we could realistically become the second biggest party in South Africa” So let us go with that.

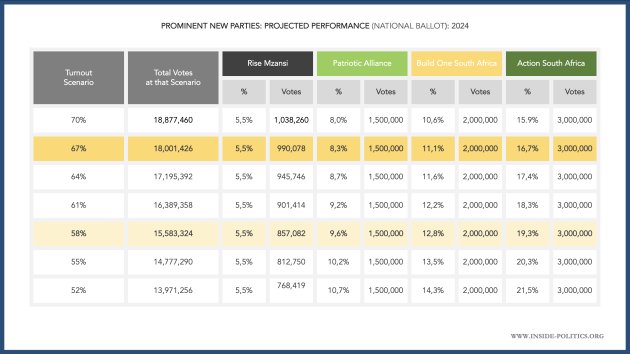

So, what do these mean for hard numbers. For RM we have a percentage: 5.5% (“conservatively between 5% and 6%”), we can work that out as votes using the current IEC total of registered voters (26,967,789). For the PA we have a vote target: 1.5m, we can work that out as a percentage, as we can for BOSA (2m votes).

ASA is a bit trickier. The second biggest party is the DA, with 21% or 3.6m votes. ASA will have to eat some of that to get to second biggest. So, let’s say 3m votes for ASA.

The IEC number will rise, especially after the next registration weekend, but the current number will serve to make a general point.

Below is a table that demonstrates what those votes or percentages would translate into, for seven turnout scenarios, ranging from 70% to 52%.

The orange band (67%) is the closest to 2019 turnout. The yellow band (58%) is where turnout would roughly be, if it drops at the same rate it did in 2019.

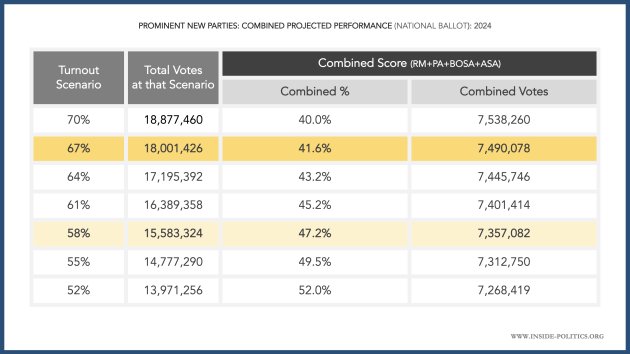

We can make more sense of just what that would translate to, if we combine all of those parties’ performances, as per the table below.

Basically, if all those parties do what they say they are capable of doing, at 67% turnout they will win around 41.6% of all votes. At 58% turnout, they win around 47.2%. There is even a scenario, if turnout drops through the floor (52%), where they win a combined majority, of around 52%. Put another way, they will win between 7m and 7.5m votes, by their projections.

To put that into context, they claim they will win three times as many votes as COPE and the EFF combined, on their first collective showings.

What would that mean for other parties? I won’t bother you with all the calculations, which are complex, but if they achieve their 58% turnout result, the current top five parties (which account for 94% of all votes) would get around:

ANC: 30%

DA: 11%

EFF: 6%

IFP: 2%

FFPlus: 1%

Finally, the latest polling – an SRF survey of 1,400 registered voters in November 2023 (disclaimer, I am the CEO of Victory Research, which conducted the poll), found the following at a 54% turnout model:

Rise Mzansi: 0,0%

Patriotic Alliance: 1.0%

Build One South Africa: 1.0%

Action South Africa: 1.0%

Now there is a 5% margin of error on that, and smaller parties are notoriously difficult to pin down exactly, so they could theoretically each be on 5% or 6%, but that is unlikely. Even then, they would be performing half as well as they claim they can, with the exception of RM.

What is more likely is that, in attempting to seem self-confident and appear “big”, these parties have predicted extraordinarily high numbers, which are unlikely to be realised. If they were, many of them would be unprecedented for first time parties in South Africa, and they would revolutionize the South African political landscape.

We will have to wait for the election to see how they each hold up against their predictions but, until then, it is probably better to adopt a more cautious approach compared to what those parties say, and when it comes to their real-world prospects.

For what it is worth, we can revisit all these predictions after the election, and see who fared best.

The key takeaways from this analysis are:

The history of new parties, with disproportionately positive media prominence and profile, suggests they overestimate their support, in part because of the entirely affirming environment in which they find themselves.

Outside of parties that have broken away from the ANC, like COPE and EFF, history suggests it is incredibly difficult for new parties to make a substantial initial impact on the electoral market.

Despite this, Rise Mzansi, the Patriotic Alliance, Build One South Africa and Action South Africa have all made extremely bold predictions for the 2024 election.

If one takes those expectations seriously and map them onto the current registered voter data base, the results are extraordinary. They suggest, if turnout drops at the same rate it did in 2019, they will win a combined 47% of all votes, and around 7m votes in absolute terms.

Were this to come to pass, it would be both unprecedented and revolutionize the electoral landscape.

The most recent polling suggests this outcome highly unlikely.

It is best to be very cautious when listening to predictions from political parties (new or otherwise) and also, not to take them at face value, especially when it comes to the media. A few simple questions, like, “How many votes or what percentage would that translate into?”, “Where will those votes come from?”, “What evidence, apart from your gut feel, do you have that this is possible?” will quickly ground hyperbole, and produce a more realistic position.

All numbers in this essay are drawn from the Independent Electoral Commission website: https://www.elections.org.za/pw/

This essay is the 7th in an on-going series on Election 2024, for all other editions of this series, please click here: Election 2024