Leadership renewal discipline and organizational culture

Introduction

1. As members of the African National Congress, we are the proud bearers of a century of exemplary leadership and service to the people of South Africa. New conditions have posed acute challenges to these traditions. The National General Council must confront these challenges head on, and deal decisively questions of renewing leadership, restoring discipline and rejuvenating our democratic organisational culture. On all these fronts the NGC should herald a period of regeneration, so that we march towards the Centenary as a strong, united and disciplined collective. The purpose of this discussion document is therefore to (a) reflect on the current challenges of leadership, discipline and organizational culture and (b) to propose possible solutions for discussion.

2. The ANC 52nd National Conference in 2007 adopted a resolution on the election of ANC leadership that affirmed ‘Through the eye of the needle?' as the organisational and political basis for the movement's approach to electing leadership. It further endorsed the provisions of the ANC Constitution that allow any member of the ANC in good standing to take part in elections and stand for elections to leadership at any level of the organisation. A decade earlier, the 50th National Conference held in Mafikeng in 1997, also adopted a document on Organisational democracy and discipline in the movement , which set out our approach to these two critical principles and approaches of the ANC.

3. Conference was determined that the incoming NEC should make it a priority to deal with all issues that must help restore unity and cohesion of the movement so that by the time of the Centenary, our movement marches together in unison. To this end, the Polokwane Conference:

- Instructed the National Executive Committee (NEC) to initiate a review of the Through the eye of the needle including guidelines on lobbying and other internal practices, learning from our experiences in the run-up to Polokwane and building on a process of political education to enhance the approaches in the document.

- Identified the need for a second discussion document, which will address a comprehensive approach to matters of leadership transition in the organisation and government, drawing lessons from other progressive parties in the world.

- Instructed the NEC to establish a period of renewal of the values, character and organisational practices of the ANC as a leading force for progressive change.

4. President Jacob Zuma emphasized the critical nature of these resolutions in his Political Overview at the March 2008 NEC meeting. The task that faces the NEC, he said, is how to initiate, guide and sustain this period of renewal. The President reiterated that:

"The ANC has not, has never been and will never be a faction...When elected leaders at the highest level openly engage in factionalist activity, where is the movement that aims to unite the people of South Africa for the complete liberation of the country from all forms of discrimination and national oppression? When money changes hands in the battle for personal power and aggrandizement, where is the movement that is built around membership that joins without motives of material advantage and personal gain? When the members of the NEC themselves engage in factionalist activity, media leaks and rumour-mongering, how can we expect the membership of our movement to carry out their duties to observe discipline, behave honestly and carry out loyally the decisions of the majority and the decision of higher bodies?"

5. However, alongside the renewal process, we have seen a continuation of serious breaches of organizational discipline, either related to misconduct in organizational meetings, leadership battles in conferences or how we engage each other in the public terrain. This prompted the NEC in November 2009 to issue this stern warning:

"The ANC constitutional structures should be resolute and decisive in stamping out ill discipline and should do so without fear or favour, as such behaviour damages the image of the ANC. Nevertheless, freedom of expression and debate within the structures should be encouraged. "

6. And yet, despite these warnings, the message has not sunk in. Attending to these issues have therefore become even more urgent, as we face the danger that these malpractices become the norm rather than the exception. Tendencies such as those referred to by the President have the potential to not only to make a mockery of attempts at organizational renewal, but to erode the character of the movement, in the process undermining its cohesion and ability to lead transformation.

The unique character of the ANC

7. Any organization that survived intact for nearly a century inevitably had its ebbs and flows. Throughout its history, the ANC had to manage internal contradictions due to its democratic and broad-based character, as well as managing struggle in the context of changing balance of forces. However, despite the lows, the African National Congress throughout this period managed to remain true to its historical mission, successfully leading the process of ending apartheid rule and laying the foundations for a united, democratic, non-racial, non-sexist and prosperous South Africa. This was mainly due its capacity over the decades to renew itself.

8. The ANC has also won its position as leader of the democratic forces through a consistent commitment to serve the people. We gained the moral high-ground through steadfastness to principle, the exemplary conduct of our leaders and cadres, a culture of openness to new ideas and debate, and a willingness to learn from others and from our own mistakes.

9. The 2000 National General Council document ANC People 's movement and agent for change, highlighted some of the reasons for this enduring capacity to renew ourselves: the capacity for self-criticism, self-reflection and correction; principled adaptability and tactical agility; steadfastness to principles, shunning shortcuts and populism; the capacity for managing internal contradictions; the centrality of the people and the belief that the people shall govern.

10. In addition, since its founding in 1912, the ANC has place a strong premium on the pivotal role of unity within its ranks. This unity was built on a culture of debate and discussion, and the commitment of everyone to implement decisions once they are taken. The unity of the ANC was also seen as important to the broader task of unity in action amongst the motive forces, in addition to pursuing the widest possible unity amongst those struggling for a better life. The ANC since its founding also embraced universal progressive values and learning from relevant international best practice. 11. Despite these characteristics, which the ANC embraced and lived over the decades, the many challenges of discipline and leadership since 1994 have begun to erode this unique character.

Negative tendencies that erode organizational culture and cohesion

12. The document Elections, lobbying and leadership transition in the ANC (Umrabulo, no. 32) highlighted how at each National Conference since the moment of entry into government, leadership transitions became increasingly problematic. Each Conference highlighted new tendencies and practices, progressively worsening and infecting all aspects of our organizational pillars and work. These tendencies and practices include: 12.1 Leadership in the ANC is seen as stepping-stones to positions of power and material reward in government and business (Organisational report to the 1997 Mafikeng Conference).

12.2 The emergence of social distance between ANC cadres in positions of power from the motive forces which the ANC represent, with the potential to render elements in the movement "progressively lethargic to the conditions of the poor."(Strategy and Tactics , 1997)

12.3 Disturbing trends of "careerism, corruption and opportunism," alien to a revolutionary movement, taking roots at various levels, eating at our soul and with potential to denude our society of an agent of real change. ( Midterm Review , NGC, 2000)

12.4 Divisive leadership battles over access to resources and patronage becoming the norm and allegations about corruption and business interests of leadership and deployed cadres abounding (Organisational report to the Stellenbosch Conference, 2002).

12.5 NEC interventions in provinces, dissolving PECs because the organization and governance became paralysed by divisions, establishing interim leaderships and having to organize early conferences. The practice of dissolving elected leadership, which initially was regarded as a last resort, has indeed become a norm across our movement.

12.6 The Stellenbosch Conference (2002), in the context of weak branches and cadre development programmes, raised concerns about members and branches being used as ‘voting cattle ', and the tendency to have recruitment and active structures mainly for the purpose of elective conferences, in the absence of ongoing programmes to organize and mobilize communities and the motive forces.

12.7 Stellenbosch (2002) also warned about the subversion of organizational culture, evident in the abuse of the ANC membership system: gate-keeping, ghost members, commercialization of membership and other forms of fraudulent practice.

12.8 These tendencies also found expression in the rise of factionalism, starting off as lobby groups towards elective conferences, and as lobbying becomes increasingly divisive, elected leadership is regarded as a faction, with leadership at highest level engaging in factional activity, decisions taken outside of organizational structures and deployment based on factionalism.

12.9 The 2005 National General Council warned about the escalation of some of these tendencies as part of the same trend of the subversion of our organisational culture: growing disrespect for organisational forums manifested in intolerance in debates; heckling, howling, indecent behaviour at meetings; resolving disagreements through violence; disrupting or walking out of meetings and conferences; allegations of the use of state resources and agencies to fight battles in the movement; elective conferences characterised by lobbying lists, block voting and winner takes-all scenarios, followed by purges or perceptions of purges and the marginalisation of sections of the movement, till the next conference when the next group takes over and does exactly the same.

13. Since Polokwane, a number of these tendencies have become embedded and in fact worsened, especially as part of the lobbying process, including:-

13.1 The influence and use of money as part of lobbying for organizational positions: This ranges from the availability of seemingly vast resources to organize lobby group meetings, travel, communications (starter-packs) to allegations of outright bribing and paying of individuals in regions and branches to vote for particular candidates, forward particular factional positions and/or to disrupt meetings.

13.2 Inability to conduct ANC meetings and affairs in an orderly and peaceful manner: We have seen a number of instances where ANC meetings or conferences were disrupted by disgruntled members, where violence were used against each other, and when the police had to be called in to intervene. In addition, the growing number of instances where members have lost confidence in our internal conflict resolutions mechanisms and therefore resort to the courts.

13.3 Winner takes all or clean slate phenomena, fuelling and breeding factionalism: More and more our approach to leadership contests at conferences is based on two lobbying lists, with hardly a name between them in common. The outcomes of elections also often reflect slates, with delegates voting on the basis of lists, winners taking all (5-0 results), those who lost leaving conferences once the results are announced and before concluding the business of conference.

13.4 Abuse of symbols and methods of struggle: Songs, t-shirts and posters that in the past were used to unite, mobilise and educate have become part of lobbying for individuals. Thus at ANC events supporters of one lobby group display t-shirts and posters and sing songs in praise of their candidates, whilst insulting other candidates.

13.4 Indecisive leadership: Since these activities also involve those at leadership level, it means that ANC leadership collectives are often paralysed by inaction, because of fears to take steps against ‘our side 'or for being accused of purging the ‘other side '. In the process, discipline is not maintained and impunity is the order of the day.

A shadow culture and subcultures

14. These tendencies have become so persistent and widespread that they in fact represent a shadow culture and subcultures, which co-exist alongside what the movement always stood for. It draws on ANC history and symbolism and like a parasite, uses the membership, and the very democratic structures and processes of the movement, to its own end. Furthermore, both ‘old 'and ‘new 'members and leadership echelons at all levels are involved, increasingly leaving no voice in our ranks able to provide guidance.

15. Thus the 52nd National Conference in Polokwane in 2007 signalled a grave warning that these tendencies "threaten the very survival of the ANC as the trusted servant of the people it has been for 96 years "and that such tendencies are "in direct opposition to everything the ANC represents, including its value system, its revolutionary morality, its selflessness, the comradeship among its members, its deep-seated respect for the truth and honesty; its determined opposition to deceit and double-dealing; and its readiness openly to account to the masses of our people for everything it says and does. "

16. This subverted shadow organisational culture has the following immediate impact:

16.1 It undermines internal democracy, cohesion, discipline, participation, membership control and the culture of debate in the movement.

16.2 It fuels public perceptions of a movement at war with itself, caring about none but itself, whose leadership (bar a few saints) are socially distant and have lost the moral high ground.

16.3 It feeds into the culture of cynicism about politics, withdrawal from political participation and channelling of participation and protest into other forms of expression.

16.4 It makes us lurch from conference to conference with leadership battles starting even before the new leadership has settled in and started to execute their mandate.

16.5 Organisational energy and efforts become so concentrated on internal affairs and squabbles, that it erode our capacity to give leadership.

17. Thus, these tendencies in the ANC impact on our ability to give strategic and moral leadership to the country, and on our historic mission to serve and unite. It is in this context that Polokwane issued the battle orders for renewal.

Objective factors contributing to organizational decay

18. The above developments and tendencies are symptoms of organizational decay that are not unique to the ANC. All progressive and national liberation movements face these challenges to some extent once they enter government or win power. We must therefore examine some of the underlying objective factors that contribute towards this situation and learn from the experiences of others.

19. We have over the last fifteen years spent a lot of time - not least at successive National Councils and Conferences - on introspection around what are essentially the symptoms, with insufficient attention to the objective factors and context which gave rise to them.

20. There are essentially five such critical underlying factors: (a) the challenges of incumbency; (b) the global ideological paradigm; (c) the impact of the mass communications and information revolution; (d) the impact of the changes over the last sixteen years; and (e) issues related to party finances.

21. The ANC, as it prepared to govern and confirmed in Strategy and Tactics after 1994, identified state power (and thus winning elections) as the most important pillar for dealing with the legacy of apartheid colonialism and the building of a national democratic society. Thus over the fifteen years we have made immense strides to transform the state, the budget and public service, and our cadreship in a short space of time mastered important aspects of this pillar.

22. However, "ruling parties are not only shaping political agendas and institutional and economic development, but also monitor the bureaucracy, control the distribution of public resources, and supervise the activities of public corporations. Parties in government play an important role in shaping the relationship between state and society, and between wealthy interests and power."(Blechinger, 2002:11)

23. The Alliance discussion document State, Property Relations and Social Transformation (Alliance, 1998) thus cautioned: "unlike the apartheid state, the NLM [National Liberation Movement] cannot rely for its political sustenance on patronage and a callous disregard of public resources and the needs of the poor. The democratic state should in principle handle public resources with respect and a sense of responsibility. This includes ensuring that public resources allocated for specific purposes actually reach the intended beneficiaries. "

24. Furthermore, the 1997 Strategy and Tactics correctly noted that the management of this process and how it impacts on the movement and its cadreship, is not simply ‘a small appendage' to the tasks of the NDR, but requires ‘all-round vigilance '.

25. This challenge - of how to use this immense power consistently and unflinchingly for the greater good and in the interest of the most vulnerable - is one that confronts progressive ruling parties and movements all over the world and in developing and developed countries alike. In pursuit of this central objective of using state power for the greater good of society and to transform power relations, progressive movements and parties had to find ways of dealing with the following issues:

- Patronage and neo-patrimonialism: including how to ensure deployment to governance based on competency and commitment to the vision of transformation, instead of deployment based on factional interests or for accessing resources; how to prevent the channeling of public resources to party structures, leaders or members; avoid the shaping of political and economic institutions to benefit narrow interest groups and preventing undue influence of those with money, connections and resources to influence elections, lobbying and access, in the process seeking to shape the national agenda.

- Bureaucratisation of political movements: blurred distinctions between movement and state; social distance between leaders, members and mass base; arrogance of power and bureaucratic indifference; demobilisation of members and mass base; domination by technocratic elites and the professionalisation of politics and a decline of activism.

- Statist approaches to social transformation: the people and citizens as passive recipients of government delivery and development; challenges to approaches of government seen as challenges to the legitimacy of government or transformation; movement and civil society structures seen mainly to support government; a paradigm of ‘good governance' vs democracy.

- Corruption: theft of public resources; abuse of position to extort bribes or kickbacks; services in exchange for bribes; business and public office conflicts of interests.

- Erosion of progressive values and organisational culture: hegemony of greed and consumption or ‘we did not struggle to be poor '; the nature of social change and growth of inequality; undermining internal democracy by limiting or seeking to discredit debates on alternatives; changing organisational culture and discipline, with enforcement of rules, increasingly for expediency rather than principle.

26. The manner in which progressive movements and their leadership - when in power for protracted periods - respond to these tendencies, fundamentally shapes the nature of the society they seek to build, influences societal values and determines whether they continue to play a revolutionary role in their societies as agents of change. Butler 's (2007:1) contention that the ANC 's "intellectual frameworks and political processes - rather than the institutions of constitutional democracy - will forge the society 's sense of collective purpose and make its key political and policy choices, "is therefore not surprising and highlights the historic responsibility on the ANC and its leadership to address these matters with all-round vigilance.

27. ANC Strategy and Tactics documents since 1997 acknowledged that the South African transition took place in a global context dominated by a neo-liberal ideology, agenda and system of values, which were not conducive to our transformation, the creation of a better Africa and of a more just world. This was not unique to South Africa. Lewis (2000: 21) writing about the democratisation of countries of Central and Eastern Europe notes that the transitions of the early 1990s took place in a global context which was "also more uncertain and potentially unfavourable for democratic transition than it was, for example for the countries of Southern Europe during the 1970s under Cold War conditions. "

28. Thus, progressive parties and movements and their leadership across the globe had to confront this paradigm, to chart development paths for their countries that allowed for a measure of national self-determination and sovereignty, which the dominant paradigm of that era sought to deny them. The ANC too had to navigate this period through the policy choices we made and the impact (and unintended consequences) these had on our development path as a country and on our movement.

29. Progressive parties and developing countries in this context, have sought to organize themselves by strengthening regional forums such as the African Union, ASEAN and Mercusor, as well as through multilateral forums such as the G77 aimed at creating more policy space for poorer countries by together fighting for a more just global order.

30. The mass communication and information revolution has had a profound impact on societies and on political and other movements across the globe. One major developments in this regard is the growing dominance of commercial media over traditional forms of communication between movements and their membership and mass base. As Leif (1998: 281), writing about media impact on European social democratic organisations rather fatalistically puts it: "In today's media society, politics enter public awareness only if the media make people aware: unless it is popular ‘prime time 'material, politics never enters into anybody 's awareness. Media politics is no small fry matter, it is dealt with uncontrolled, in private. This in turns defines the specific direction of the lobbying within parties. "

31. New media and communications technology also increase the ability of people to speak to each other directly and instantly across large distances, rather than waiting on official organisational channels. On the one hand, the availability of this technology is good for democracy and the free flow of information. On the other hand, it can mean that the ‘official 'voice of the organisation is always struggling to be heard in a cacophony of direct interactions between comrades. An example of this in our own ranks is the frequent use of SMS's as a tool in internal battles by spreading factional messages and misinformation.

32. The ANC in rising to this challenge has often been in the forefront of strategies to engage with this new reality, including the fact that the movement was the first political party in South Africa to start its own website in 1995. It regularly uses research and opinion surveys to aid its elections strategy development, while at the same time emphasising internal communications (through organs such as ANC Today, NEC Bulletin, Umrabulo and the growing number of provincial publications) and direct communications with its mass base. The innovative use of ‘new media 'was particularly evident during the 2009 elections campaign, and is one of the explanations for the concerted outreach to young and first-time voters. Part of the ongoing challenges of the ICT revolution also include engaging with the rise of user-generated content, and the potential for instant messages to reach increasingly larger groups of people.

33. The negatives of the information revolution include the shallowness that is associated with instant and constant news feeds, short attention spans and the tyranny of the sound bite. For political movements and parties there is also the challenge of leaders who are made in the media or who have to be ‘media friendly '. In response, organisational programs (and often policies) too become ‘instant 'and responsive and the media is then used to forward agendas within organisations. One of the manifestations of the shadow organisational culture in the ANC of the last couple of years have been the public spats between leaders and the use of the media to discredit each other and to fight internal leadership battles in the movement and the Alliance.

34. The engagement on the issues of communications remains an important part of ANC organisational strategy, as recognized by the extensive resolution from the 51st National Conference in 2002 on Communications, which also set clear benchmarks. This resolution re-affirmed and extended the policy positions of the previous conference, in the context of the battle of ideas.

35. The foundation built during the first sixteen years of freedom, developments on the African continent, the global environment as well as the simple passage of time already had an impact on the nature of our society. These include changes among the motive forces, such as for example

- the Shifts in trade union membership from the dominance of workers from primary (mainly mining) and secondary sectors towards services (public sector), reflecting shifts in the country's economy and labour markets;

- The growth of the black middle class and a small, but visible black bourgeoisie, also in many cases with a strong link to public sector activities or sectors of the economy that are highly regulated.

- The impact of urbanisation and of internal and external migration; The persistence and changing nature of the national and gender questions; The persistence and changing nature of inequality and poverty; and The reality of post-apartheid generations with their different experiences, issues and perspectives.

36. Many of these developments are a result of our success and the process of liberation in general. However, the organisational challenges also reflect our lack of success in other areas. For instance, to the extent that the economy is not growing enough to create real opportunities in productive economic activity, people will seek to accumulate wealth by using the state apparatus. Also, to the extent that we are unable to ensure the effective delivery of public resources on an equal and consistent basis, people may try to use structures of the organisation to divert resources or ‘jump the queue 'in service delivery.

37. The challenges of leadership document thus recognised the necessity of the ANC in its leadership collectives to embody these changes, arguing that our collectives are ‘melting pots ', which should be seen to represent a "synthesis of not one but the cross-section of various strands and identities. Overall, the ANC should strive to be the microcosm of the motive forces of transformation and in broader terms, the microcosm of the South African nation being born. "

38. The eye of the needle (ANC, 2002: par. 6 and 11-17) urged members when considering nominations for leadership to ensure that these collectives reflect the current tasks of the NDR - of building a national democratic society. This should find expression in the kind of ANC required to meet these challenges: a mass people 's movement, a non-racial and non-sexist national movement, a revolutionary democratic movement, a leader of democratic forces and a champion of progressive internationalism.

39. The financing of the movement (and other parties and organisations) and how this could be used to influence leadership and policy outcomes and the integrity of the ANC is a growing concern. This, however again does not only confront the ANC or South Africa. The research institute IDEA (2003:v) in its Handbook on Funding of Political parties and elections campaigns, notes that:

"Parties need to generate income to finance not just their electoral campaigns but also their running costs as political institutions with a role to play between elections. Yet parties, in newer as in older democracies, are under increasing pressure, faced with a vicious circle of escalating costs of campaigning, declining or negligible membership income, and deepening public mistrust about the invidious role of money in politics. Their problems of fund-raising are causing deep anxiety not just to politicians but to all those who care about democracy.

The issue of party finance has in the past been dealt with in sharply contrasting ways across the world, but there are now signs of some convergence in the debate. There are at least three distinct but interrelated questions: (a) how free should parties be to raise and spend funds as they like? (b) how much information about party finance should the voter be entitled to have? (c) how far should public resources be used to support and develop political parties?

Each of these questions raises others about the function of political parties in society and reminds us of how much remains to be done, even in some quite stable democracies, to have political parties act according to basic principles of transparency and the rule of law. There are no simple answers about how political finance should be organised. "

40. Mindful of these issues, the 52nd National Conference resolution on Funding (ANC, 2007 par. 63) was therefore unambiguous in the policy positions it adopted: "The ANC should champion the introduction of a comprehensive system of public funding of representative political parties in the different spheres of government and civil society organisations, as part of strengthening the tenets of our new democracy. This should include putting in place an effective regulatory architecture for private funding of political parties and civil society groups to enhance accountability and transparency to the citizenry. The incoming NEC must urgently develop guidelines and policy on public and private funding, including how to regulate investment vehicles. "

41. The above approach primarily addresses formal party funding. But what about monies raised by candidates and lobby groups, with no accountability and disclosure about the sources (and legality) of such resources, nor how these monies are being used? Are we already in the trap of vested interests and those with money having more influence about the direction of the ANC than its membership?

42. Our approach towards party financing will therefore have to be broader, so that it also deals with the "informal "party financing, which is so much more insidious and dangerous to internal democracy.

43. These five issues are part of the objective reality confronting the movement today. Recent Strategy and Tactics documents have reaffirmed the ANC as both a revolutionary movement and a disciplined force of the left. This includes reaffirmation of its commitment to social transformation and to the centrality of the people in this process. The ANC must therefore draw on its traditions of struggle, learning from global best practices and its own innovations to provide moral and people-centred alternatives to any paradigm that seeks to undermine the human dignity of our people. It is thus an affirmation that we are not merely prisoners of our situation, but that we have it in our powers to bring about changes.

Polokwane - the call for renewal

44. Against this backdrop, and mindful that we were approaching fifteen years since our democratic transition, the 52 nd National Conference in 2007 was an important moment in the history of the movement. It drew attention to and re-affirmed important organizational principles of the movement, such as:

44.1 The centrality of the people: It reasserted the perspective that the ANC remains a liberation movement that exists primarily to serve the people. As a ruling party, the ANC should therefore use access to state power to change both the state and society in order to benefit the people and improve their quality of life. Polokwane therefore overwhelmingly rejected any attempt to turn the ANC and the state into instruments for self-enrichment and self-aggrandisement.

44.2 The role of the membership and grassroots: It reaffirmed and reasserted the democratic character of the ANC, especially the critical voice of the rank-and file membership and grassroots structures in giving direction to the ANC. Leadership must be humble and accountable to the base, always serving at the pleasure of the membership and branches.

44.3 Relationship between the party and state: It adopted the perspective that the ANC is a strategic centre of power that should lead both the state and society in the transformation of SA. It reaffirmed the ongoing relevance and centrality of the Alliance and called for ways to strengthen the Alliance.

44.4 The need to reassert our revolutionary morality and values: including the values of service to the people, human solidarity, humility and selflessness.

44.5 The centrality of discipline: reaffirming the position adopted at Stellenbosch that the ANC indeed remains a revolutionary movement and disciplined force of the left, which requires leadership and cadres with revolutionary discipline and conduct. 45. It is against this background that the 52nd National Conference made a clarion call for renewal. However, Polokwane Conference 's historical significance will be judged based on whether it was a turning point to arrest and reverse the danger of revolutionary decline and decay posed by sins of incumbency. We will remember Polokwane in so far as it launched the renewal campaign to safeguard the ANC 's legacy as the people 's movement and agent for change for next generations.

Answering the call - critical issues in the battle for renewal

46. Renewal is not an easy battle to win. Those who benefit from the current chaos and decadence will resist renewal. It will take a decisive leadership, committed cadreship and politically conscious membership to succeed in winning the war against organisational decay. The NGC discussion document on Organisational renewal , will deal with the details of the organizational tasks and progress on renewal. This document deals with issues with regards leadership renewal, organizational discipline and culture.

47. Leadership renewal, and addressing the challenges we face in our leadership elections and succession planning, will be an important part of renewal of the movement towards the Centenary. The following are amongst the issues that require urgent attention in this regard:-

48. The discussions towards the 2000 NGC (reiterated in January 8, 2010 statement) raised very sharply the issue of the movement taking the lead in defining a new morality, which should help us construct and form the foundation of the national democratic society we seek to build. The discussion document "ANC revolutionary movement and agent for change "of 2000 thus raised the need for a New Cadre and Person, in the context that the National Democratic programme is about both the transformation of material conditions and about engendering new social values.

49. Failure to build a New Person (continued the 2000 NGC document), among revolutionaries themselves and, in a more diffuse manner in broader society, will result in a critical mass of the vanguard movement being swallowed in the vortex of the arrogance of power and attendant social distance and corruption, and, ultimately, themselves being transformed by the very system they seek to change. An important challenge, among others, is thus to ensure a systematic intervention by the ideological centres and institutions of society, as well as mothers and fathers and the family as a whole in shaping social values and a new morality.

50. The process of engendering new social values will require comradely and frank debates about the nature of the society, institutions and values we espouse and live by. It will require introspection and reflection on the role and image of the movement as a leader of our society, as well as self-reflection by its leaders and members on our collective and individual contribution to the shaping of this role and image.

51. Strategy and Tactics (2007: par. 35-38)) dedicates a substantive discussion to the value the national democratic society we seek to build, as an antithesis to the historical injustice of apartheid colonialism, but also as an antithesis to a narrow national liberation struggle ending at formal political power, as well as to neo-liberalism and ultra-leftism. The foundations of a national democratic society, it notes, should include sustainable use of natural resources for current and future generations; management of human relations based on equality; social inclusion, opportunities for youth and protection of the vulnerable; a state which derives its legitimacy from the people, with checks and balances of the rule of law; and a nation acting in partnership behind a common vision, each sector making its contribution and recognition of diversity as well as our overarching national, African and human identity.

52. The value system of a national democratic society is also critical to social cohesion and inclusion and essential component of our vision for society. Constructing a national democratic society requires a value system based on a caring society, human solidarity; a focus on the rights of the poor; discouraging conspicuous consumption and ostentatiousness; promotion of social activism; pride in an honest day 's work, and rooting out corruption.

(b) Exercising political and state power in the interest of the people as a whole

53. Strategy and Tactics (2007: par. 138) recognizes the challenges and ‘sins 'of incumbency (patronage, bureaucratic indifference, arrogance of power, corruption) and suggests approaches to the management of relations within the organization. Our ability to manage this minefield, it contends, will determine "our future survival as a principled leader of the process of fundamental change, an organization respected and cherished by the mass of people for what it represents and how it conducts itself in actual practice. "54. These approaches should show a fundamental appreciation of political power and the role of the state to the building of a national democratic society. The principles that should inform our approaches to the management of state power as ANC cadres include:

54.1 Treating politics and public service as a calling with requisite moral status, in which any of the motive forces can take part, ether as a profession or as time-bound service.

54.2 Strategic leadership by the ANC to deployed cadres in government, through its policy making forums, thus acting as political centre.

54.3 Strengthening ANC monitoring and evaluation capacity, in order to ensure our strategic mandate is carried out, direction given to cadres and space provided for cadres to exercise initiative within their strategic mandate.

54.4 Provide systems of information sharing within leadership structures and across the organization.

54.5 Ensure cadres apply themselves to government work and add strategic value. 54.6 Manage the state as an organ of the people as a whole, rather than a party political instrument.

55. These are noble principles, but we must discuss, apply and review on an ongoing basis how we practically live up to these, at all levels of the state. Key to this will be building the capacity of the ANC to monitor and evaluate the implementation of its politics and to hold its representatives and deployees accountable. In addition, the participation of the people in their own transformation and development, and the responsiveness of the ANC to the people is a critical success factor.

56. The factionalism that is associated with a shadow organisational culture breeds intolerance, removing the vibrancy of debate and the mutual development of members that are the life-blood of the organisation. Disruptive conduct in meetings and conferences, including shouting down those who hold contrary views and even indecent and violent conduct, can become the order of the day. If this is allowed to continue, many members will recoil from taking part in ANC meetings. Some may simply let their membership lapse, and all kinds of rogues may take the movement over - with dire consequences for the ANC and indeed the revolution as such.

57. A critical area is therefore to ensure that gatherings of the movement, where members exercise their rights and responsibilities, are conducted in a proper manner. Box 1 is an example of the kind of lines between appropriate and inappropriate conduct we must consider.

BOX 1: CONDUCT IN GATHERINGS

In meetings, ANC members have a right to contribute to discussion on any issue, in line with meeting agendas and rules. This includes matters pertaining to debate on candidates for election into any position or selection of delegate(s) to Conferences. In such discussion, members have the right to be "wrong "; but should accept the view of the majority when such a view has been procedurally adopted. Respect for meeting rules are an important part of ensuring that the organisation is able to conduct its affairs, and to allow all members to contribute to the political life of the movement.

Acts of misconduct in gatherings already in the ANC Constitution (Rule 25.5) and which need to be discouraged:

- Undermining the respect for or impeding the functioning of the structures of the organisation;

- Participating in organised factional activity that goes beyond the recognised norms of free debate inside the organisation and threatens its unity;

- Fighting or behaving in a grossly disorderly or unruly way; and

- Deliberately disrupting meetings and interfering with the orderly functioning of the organisation.

In line with these and other provisions of the Constitution, the following should also be prohibited:

- Preventing other members from stating and arguing their points of view, including through heckling or other disruptive activities;

- Forcing one 's way into meetings which an individual does not have the right to attend, refusing to abide by accreditation rules or allowing such conduct;

- Suppression of legitimate dissent which is aired in accordance with the rules of the meeting or otherwise generally ignoring procedures on how a meeting should be run;

- In the meeting, as a candidate, failing to take steps, including interactions and/or statements to stop misconduct in one 's name; and

- As an accredited observer or guest, engaging in conduct that violates these and other rules of the ANC.

****

(d) Review and strengthen core aspects of our internal electoral presence

58. Through the eye of the needle' (ANC 2001: par. 18-24) spells out the principles of ANC organisational democracy. These include elected and collective leadership, branches as basic units of the ANC, consultations and mandates, criticism and self-criticism, democracy as majority rule and the applications of democratic centralism.

59. ‘In addition to the above principle, the constitutional guidelines for elections provide for a critical role for branches and branch members as the electoral college for all elective positions in the ANC. These principles and guidelines - the right of any member to stand and be elected subject to qualifications in terms of track record; the nominations process in branch general meetings; the election of delegates to conferences; nominations from the floor at conferences; and voting by secret ballot - are critical to a democratic organisation.

60. However, the shadow culture we spoke about undermines and subverts these very processes. Eye of the needle thus reminds us that members must take charge, identifying a critical challenge facing branches to ensure the integrity of the membership system. It also addresses the responsibility of conference delegates to deliver the mandate of their branches, while also allowing themselves to influence and be influenced by other delegates.

61. A major challenge is how to ensure the integrity and rigour of the electoral processes. Discussions about leadership in branches should be based on the tasks at hand and the requirements of leadership, rather than members simply being roped in to support one list or another, without debate and discussion on the tasks of the movement and without consideration of what each individual candidate can and should contribute.

62. Our current electoral process is thus based on the revolutionary assumption that the organisation through its membership and structures discuss the requirements of leadership and who best in its ranks can fulfil these tasks. One of the tendencies of the last fifteen years has been of individuals or groups aspiring towards leadership, and then seeking to convince the organisation and members to nominate and elect them, often in opposition to another group - either getting them out or preventing them from coming in. This tendency is counterproductive when it is based not on the tasks at hand and qualities of individuals, but on expediency (getting in at all cost) or a half-baked vision with little intention of uniting the movement behind such vision. Thus means and ends become equally suspect.

63. We thus need to find a way of strengthening our electoral processes generally and the nominations process in particular, by:

- Circulating electoral rules and other guidelines for conferences way in advance, so that the organisation sets the debate about conferences, rather than individual agendas as played out in informal processes and in the media.

- Incorporating the ‘broad criteria for leadership 'into our electoral rules to ensure political discussions on candidates for nominations; and

- Developing guidelines on lobbying, with structures to enforce it (see for example Box 2 ).

BOX 2: RULES ON LOBBYING

A democratic electoral process is about influencing and being influenced by others about the value that a candidate will add to the work of the organisation. As such, structures, members and even the candidates or aspirant candidates have a right to express their views, in the process influencing the electoral process and allowing themselves to be influenced in the process of engagements about these issues. This will take place in informal interactions as well as in formal structures of the movement.

However, no structure outside of the ANC has a right to nominate or lobby for any candidate. While appreciating that the public at large will have an interest and even preferences, which in a free society may be publicly expressed, mobilisation for such support, including setting up of lobby-groups that seek to influence internal ANC processes, by candidates or their supporters should be prohibited. We should therefore consider discouraging the following specific wrongful lobbying practices, by adding them as acts of misconduct in our electoral rules, including:

- Raising and using funds and other resources to campaign for election into ANC structures;

- Production of t-shirts, posters and other paraphernalia to promote any candidature; Promising positions or other incentives or threatening to withhold such, as a means of gaining support;

- Attacks on the integrity of other candidates, both within structures of the movement and in other forums, save for legitimate critiques related the substance of the contestation which should only be raised in formal meetings of the movement; Suppressing honest and legitimate debate about candidates (on these issues of substance) in formal meetings of the movement;

- Open and private lobbying or utilisation of the media in support of or opposition to a particular candidate;

- Allowing structures or individuals to condone violation of Constitutional provisions and/or regulations, and/or failing to report such violations when they occur; and

- Generally, as a candidate, failing to take steps, including interactions and/or statements to stop misconduct in one's name.

****

(e) Sanctions and enforcement

64. Attached to all rules should be sanctions that fit the level of misconduct. Many of these are contained in the Constitution, and include suspension and even expulsion. However, in the context of electoral processes, additional sanctions and enforcement mechanisms are necessary, which will serve as a disincentive directly linked to the context of the misdemeanor, including:

- Disqualification as a candidate or delegate;

- Expulsion, from the meeting, of a candidate or delegate or observer or guest; and/or

- Naming and shaming of candidates or members or their ANC/non-ANC supporters.

65. The rules proposed for discussion are meant to reinforce the processes started to renew the values, character and organisational integrity of the ANC. They are not meant to supplant, but rather to reinforce, the other elements of this campaign such as political education and induction. As with all rules, they can lend themselves to partial application or perceptions of such; or galvanise an industry of legal expertise to find loopholes of avoidance. This should be obviated through the utilisation of the movement 's disciplinary structures in finalising the details, proceeding from the perspective that the ANC is a voluntary organisation.

66. It should be expected that, once the system is put in place and sufficiently publicised, it would serve as a deterrent at least to the most vulgar expressions of ill-discipline that we have witnessed in the recent period. Further, it is hoped that consistent application of the system, especially in the early stages, will be indication enough that there is consequence to delinquency.

67. For any revolutionary movement, the reproduction and maintenance of its organisational culture and leadership cannot be left to chance. ANC branches and the Leagues are important ‘schools of socialisation'in this regard.

68. ANC branches are the first point of entry and (should) provide the most consistent and vibrant forums for members to participate in the political life of the ANC, and thus for the development and emergence of leadership. That is why the twin tasks of branches include mobilizing and organizing communities and as a political school for members of the ANC. It is in branches that we should learn the values of social activism and an understanding of the basic policies and principles of the movement. 67. The Youth and Women 's Leagues, as sectoral formations of the ANC and through their branch structures, also have similar yet specialised functions. The ANC Youth League serves as a preparatory school for young members and leaders, by harnessing their energy, innovation and enthusiasm in the transformation process. As a mass movement of young men and women, it also provides young activists with practical experiences of mass work, problem solving and service to the people. In addition, it mobilises and champions youth interests in the ANC and in broader society. It is therefore not surprising that from the ranks of the ANC Youth League have emerged tried and tested cadres and leaders of the ANC.

69. The ANC Women 's League is a political school for women, harnessing the reservoir of community activism we find among women virtually everywhere, raising their consciousness and awareness about their position and emancipation as women, the building of a democratic, non-racial, non-sexist and prosperous country for all, and preparing them to take their place in the ANC and in broader society, pursuant of these goals.

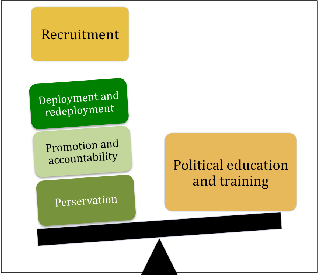

70. The recently launched Veterans League is a unique formation, an embodiment of the organisational experience and memories of our movement. It should thus play a critical role in the process of political education, socialisation and leadership development. 71. The Kabwe Consultative Conference in 1985 adopted a resolution on cadre policy, which sought to institutionalise the process of cadre and leadership development in the movement. This policy, and subsequent resolutions recognised the importance of the development, deployment, promotion, accountability and maintenance of cadres.

Figure1: Critical elements of a Cadre Policy

From: Kabwe National Consultative Conference (1985) Commission report on Cadre policy

72. Thus since Mafikeng in 1997, the ANC adopted resolutions on deployment policy and the roles and accountability of our public representatives and deployed cadres, because we recognise the role the state plays in shaping and driving the social transformation agenda and that this too should not be left to chance.

73. What has been lacking is a deliberate human resource development programme for the ANC, which encourages and creates opportunities for training and gaining experience in the myriad of spheres necessary to build a national democratic society. The implementation and coordination of such a policy should allow for a more conscious and transparent process of career-pathing by party cadres, and will also strengthen our deployment policies at all levels.

74. The NEC Lekgotla in January 2009 also pronounced on leadership conduct, calling for the development of an ABC of Congress leadership , which should spell out our basic approaches to leadership, and the conduct expected from ANC leaders at all levels. 75. A strong call emerged from Polokwane for us to refine our approaches to leadership transition and succession, including learning from other progressive movements and parties. This should allow us as we approach elective conferences of whatever structure in the movement to be prepared not only to consider the tasks at hand, but ensure that leadership transition takes into consideration intergenerational learning, balancing continuity and change to ensure the preservation of organisational memory and experiences, as well as renewal and replenishment. This, according to the Polokwane resolution, should be the subject of a separate discussion paper.

Conclusion

76. The 52nd National Conference will go down as the Conference that not only raised the alarm about the negative impact of incumbency, it also called for renewal to defend the traditions of the ANC as a liberation movement that must remain loyal to the people of SA. It marked a moment for self-reflection, self-correction and adaptation to new challenges.

77. The drive for the organisational renewal of the ANC should help pave the way for critical reflection and debate, creating an atmosphere where we can collectively find lasting solutions to these very difficult problems. This requires leadership to lead honestly, humbly and decisively, and for membership and cadres to ensure that we take responsibility for the health of our movement.

78. In the run-up to the Centenary and Second Decade, we should unveil a comprehensive campaign and programme of renewal at all levels. As we prepare for the Centenary of our movement and the end of the Second Decade of Freedom, we dare not fail!

REFERENCES

African National Congress. All documents on www.anc.org.za

‐ (2009). "Decisions of the NEC". NEC Bulletin, November 2009, p. 6.

‐ (2007). Building a national democratic society. Strategy and Tactics of the

ANC as amended and adopted by the 52nd National Conference, 2007. Johannesburg: ANC.

‐ (2007). "Resolutions: 1. Organisational renewal. Election of ANC leadership." 52nd National Conference Report, Polokwane, 16‐20 December 2007, p. 17.

‐ (2007). "Resolutions: 9. Communications and the Battle of Ideas.." 52nd National Conference Report, Polokwane, 16‐20 December 2007, pp. 59‐63.

‐ (2001). "Through the eye of the needle - choosing the best cadres to lead transformation." Umrabulo, No.11, June‐July 2001.

‐ (2000). "ANC - people's movement and agent for change." Umrabulo, No. 8, Special Edition, May 2001.

‐ (1997). "Challenges of leadership in the current phase." Umrabulo, No. 3, July 1997.

‐ (1997). "Organisational democracy and discipline in the ANC." Umrabulo, No. 3, July 1997

‐ (1985). "Report of the Commission on Cadre Policy." ANC National Consultative Conference, Kabwe.

Alliance (1998). "The State, property relations and social transformation." A discussion document towards the Alliance Summit. Umrabulo, no. 5. 1998

Blechinger, Verona (2002). "Corruption and political parties." Sectoral perspectives, November 2002. MSI

Butler, A. (2007). "The state of the African National Congress". Buhlungu S, Daniel J, Southall R and Lutchman J (eds). State of the Nation. South Africa 2007, pp. 35‐52. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

IDEA (2003) Funding of political parties and election campaigns. Handbook series. Stockholm: International IDEA.

Source: African National Congress discussion documents prepared for the National General Council 20-24 September 2010. Transcribed from the PDF - as such there may be errors in the text.

Click here to sign up to receive our free daily headline email newsletter