Build elements of, capacity for, and momentum towards socialism

The past 20 years and the next 10. Political report to the SACP Central Committee, December 2013

Our 1995 7th Congress adopted an important programme, in the form of a strategic perspective, Socialism is the future, build it now. This perspective has always guided our Party since then, to anchor our role in the immediate post 1994 period, immediately after the democratic breakthrough of 1994. In fact, the primary theoretical and strategic content of building working class hegemony in all key sites of power and sites of struggle must be the struggle to roll back the capitalist market.

In fact, there is a deeply dialectical relationship between perspectives contained in our 1995 document and our current programme, The South African Road to Socialism. Our 1995 strategic perspectives laid a strong foundation for a campaigning SACP from 1999 onwards with its own distinct campaigns.

Similarly these campaigns are meaningless and will have no direction unless understood within the context of building capacity for, momentum towards, and elements of socialism, in the here and now. In fact, the main content of the second phase of our transition must be characterised by rolling back the capitalist market as part of driving a developmental agenda that will benefit the majority of the workers and the poor.

For the SACP the main content of the second, more radical, phase of our transition must be driven through building capacity for, momentum towards and elements of socialism in the here and now. It is only such measures that can ensure that we realize a radical break with the current semi-colonial growth path, building on the very important policy breakthroughs and government programmes (like infrastructure) that are in place now.

This Augmented Central Committee (ACC) must reflect on the past twenty years and the last five years of governance, especially the SACP's participation and lessons to be learnt out of this. This assessment must be subjected to our own programme and strategic perspective of building socialism now through building working class hegemony in all key sites of power and fronts of struggle.

Towards the 20th anniversary of democracy in SA - why we need a second radical phase of the NDR

The celebration of the 20th anniversary of our 1994 democratic breakthrough AUGMENTED CC Build elements of, capacity for, and momentum towards socialism The past 20 years and the next 10. Political report to the SACP Central Committee, December 2013 AFRICAN COMMUNIST | December 2013 8 will be used by the ANC alliance as a central theme of next year's election campaign.

This is perfectly correct. However, it is important that the manner and content given to this celebration is based on a clear analysis, including a CLASS analysis of what has transpired over the past two decades - otherwise the campaign will lack credibility amongst our mass base and, above all, will not sufficiently underline the reasons why we need now to consolidate a second radical phase of the democratic transition.

It is impossible to understand the need for (and the nature of) this second radical phase without understanding the following apparent paradox:

Things have generally improved for the majority of South Africans, including the working class and poor - but

The balance of class forces has generally worsened for the working class and poor relative to the power of monopoly capital since 1994.

The first part of this paradox, the story of important positive changes and victories since 1994 should be well-known to us, but it bears constant repeating - particularly to counter the pessimists and doomsday prophets in the media and opposition parties who argue that "things are worse than they were under apartheid". It is a message designed to sow despondency, pessimism about the ANC-led alliance, and even a loss of faith in popular power and our new democracy.

It is a message taken up by both the right and ultra-left.

Besides the critical consolidation of a non-racial democratic dispensation within a unitary state and the entrenchment of a progressive Constitution, the many socio-economic achievements include:

The lifting of the floor of poverty through, amongst other things, the roll-out of social grants. The number of South Africans receiving social grants has risen from 2,4million in 1994 to an impressive 16,1m at the present.

An increase from 13,8m (2001) to 23,5m (2010) of those in the LSM 5-10 bracket (LSM stands for Living Standards Measure, and brackets 5-10 are regarded as "middle" and "upper" strata).

- The reduction of those living below the poverty line to 9% of the population.

- Households with electricity rising from 58% in 1996 to 85% in 2011.

- Between 2- to 3-million RDP houses.

- Sanitation and water connection rollouts.

- The (belated) rollout of ARVs - the largest ARV programme in the world - now beginning to have a tangible impact on life expectancy (after a drastic drop).

- A significant impact on adult illiteracy.

- These are all remarkable achievements and they have everything to do with the progressive role played by the ANC-led alliance and the new democratic government.

However, these and other major socio-economic gains have been made "against the flow" of the dominant growth trajectory, they are the result of government-led efforts and (to a lesser extent) of popular struggles. They have been largely based on efforts of reform and redistribution at the margins - a redistributive politics of "delivery" out of surplus without fundamentally transforming the productive economy itself.

Because of this, all of the gains achieved are threatened, and many already have been hollowed out.

South African monopoly capital has been the major beneficiary of the 1994 democratic breakthrough

To understand the dominant growth path trajectory over the past two decades it is useful to return to the early 1990s. An important factor in the 1994 democratic breakthrough was the strategic realisation by South African monopoly capital (and the media and research think-tank apparatuses that advanced its interests), that white minority rule, having served monopoly capital's objectives very well for decades, was no longer viable. The cost of waging regional wars, notably in Angola and Namibia, the instability at home as a result of the rolling semiinsurrectionary waves of resistance, and international sanctions, particularly financial and oil sanctions, had all led to a significant decline in profitability.

This was an important factor behind the emerging national consensus for an advance to some kind of non-racial democracy that opened up the negotiations process. However, there were two very different class strategic agendas at play in this "consensus":

For the broad liberation movement a democratic breakthrough was seen essentially as a platform to advance immediately (certainly as far as the SACP was concerned) with what we now call a "second phase" of radical transformation.

For South African monopoly capital it was almost the exact opposite. The establishment of a formal non-racial democracy was seen as a "necessary risk" to open up the region and world to South African business and restore profitability. The strategic objective was to create a "formal", "low intensity" democracy in which majority power would be checked and balanced through a wide range of institutional and other arrangements, including making "delivery" of "change" dependent upon and hostage to capitalist-driven growth.

The idea was also to tame the ANC - partly through fomenting an Alliance break-up. Writing in 1992, Frederik Van Zyl Slabbert captured this overall strategic agenda well when he wrote: "one of the most daunting challenges facing [a future ANC government] is to protect the new political space created by negotiations from being used to contest the historical imbalances that precipitated negotiation in the first place... " In other words, for monopoly capital and its ideologues, the strategic objective of moving towards a democratic settlement was not to advance radical transformation - but to forestall it.

On balance, it is this latter strategy that has prevailed - not because it was wrong of the NLM to pursue a negotiated settlement, not because of any major constitutionally imposed limitations, and certainly not because (as the ultra-left alleges) we were pursuing an NDR strategy. In fact, the problem was that from around 1996 there was a failure to decisively and confidently pursue an NDR strategy within the new democratic space and with an overwhelming electoral majority - as a result, the second radical phase of the NDR was postponed.

The illusions of a social democratic social accord with monopoly capital

This relative failure was, in part, the result of another failure - a misreading in the early 1990s of what we were dealing with from the side of South African monopoly capital. There was an illusion that it would be possible (and desirable) to pursue a patriotic, "win-win", "social democratic accord" between labour, the AFRICAN COMMUNIST | December 2013 10 new ANC-led administration, and South African monopoly capital. The model that was assumed to be applicable to post-apartheid SA was a re-play of the social democratic pacts that operated in much of post-World War 2 Western Europe through to the early 1970s (the "golden epoch" of capitalism).

Perhaps this was not an illusion, but part of a deliberate strategy to consolidate a particular relationship between the post 1994 state and monopoly capital.

This could be especially so given the dedicated placement and training of our cadres who played a very key role in the evolution and driving of the 1996 class project. Some were sent to Goldman Sachs, Harvard School of Government, etc, as well as the role they played in sidelining some of the key research and analyses by the Macro-Economic Research Group.

Nevertheless.... The illusion that SA in the 1990s was ripe for such a patriotic pact was grounded on three interrelated illusions:

It failed to appreciate that South African monopoly capital (unlike West European capital in 1945) had not been ravaged by war, with factories destroyed and a work force scattered or disappeared.

In the interests of restoring profitability, post-WWII West European capital was inclined to act "patriotically", by investing in national reconstruction and development - re-building destroyed economic and social infrastructure, investing in training, and paying high tax rates. By contrast, while South African monopoly capital had suffered declining profits and growth rates through the 1980s and early 1990s, it was not on its knees. Sanctions and strict foreign exchange controls had led to increasing accumulation of surplus within the country, leading to growing conglomeration with inter-twined mining and finance capital moving into manufacturing, forestry, logistics, retail, property and services. SA monopoly capital looked to a democratic transition as an opportunity to disinvest out of the country, to globalise, to financialise and to unravel its diverse multi-sectoral holdings by focusing on key assets to maximise "share-holder" value. Patriotic investment into national reconstruction and development was not a priority.

The social democratic illusion in SA also failed to appreciate that not only was SA 1994 not Western Europe of 1945, but that the developed capitalist world itself had changed since 1945. The hey-day of social democratic accords, even in the Nordic countries, had long since come and gone. The very successes of these social accords in achieving near full employment and an extensive social wage had greatly strengthened the bargaining power of the working class and popular strata (although still within the confines of a capitalist system). This resulted in the social pacts entering into a period of conflictual stagnation (expressed economically in rising inflation), which was eventually "resolved" through a class offensive against labour and the welfare state (Thatcherism) and what later became known as neo-liberal policies (monetarism, Reaganomics, etc.) which enabled national monopoly capital to break out of national compacts, spurring on three decades of accelerated globalisation in pursuit of cheap labour markets in the developing world, and growing speculative financialised activity.

The 1994-era South African longing for a Nordic style social pact also failed to appreciate that the post-war reconstruction of Western Europe (and Japan) was greatly assisted by US aid (Marshall Aid) AFRICAN COMMUNIST | December 2013 11 in a particular conjuncture that no longer applied globally in 1994. It was thought that a democratic SA would benefit from major flows of foreign direct investment as a result of our "universally acclaimed" good behaviour in achieving a negotiated settlement. But in 1945 Keynesian economics, not neo-liberalism, was the globally dominant ideology in the capitalist world. Perhaps an even more important contrast was that US aid to promote (capitalist) reconstruction and development in Western Europe and Japan was driven by the new competing reality of an expanding socialist bloc in East European and (after 1949) in China. In 1994 this "threat" was no longer felt in the US.

It is important to remind ourselves of all these contrasting geo-political and economic realities - because the social democratic illusion of an all-in, multiyear social pact with monopoly capital is still being held up as SA's best hope in the National Development Plan (NDP), for instance. This is how the NDP envisages the social accord that lies at the heart of its overall political vision:

Labour agrees "to accept lower wage increases than their productivity gains would dictate". While business agrees "in return...that the resulting increase in profits would not be taken out of the country or consumed in the form of higher executive remuneration or luxuries, but rather reinvested in ways that generate employment as well as growth." (NDP, p.476).

The hopelessly utopian nature of this proposal is emphatically underlined by what has actually been happening over the past 20 years of democracy in South Africa. As even the recent Goldman Sachs 20-year report card on South Africa acknowledges, labour productivity has far out-stripped wages. According to the Goldman Sachs report labour productivity per worker trebled in a decade - from around R88 000 in 2002 to around R256 000 in 2012. (Of course, these productivity gains have been achieved largely through increasing capital-intensity with mass retrenchments of semi-skilled workers).

Notwithstanding these dramatic increases in labour productivity and resulting increases in profits, monopoly capital has generally done the exact opposite of what the NDP hopes it will do - paying itself higher executive remuneration, consuming imported luxuries, and not re-investing but disinvesting and/or maintaining an investment strike while diverting surplus into financialised speculative activity.

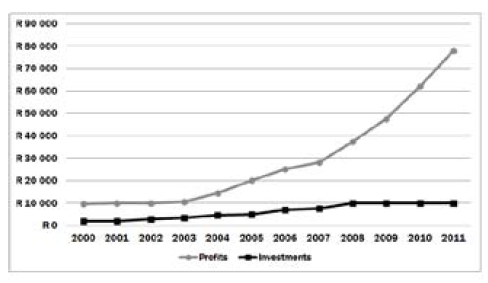

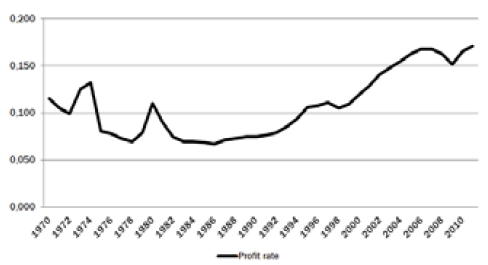

Reinvestment of profit: SA construction industry

Profit rate in SA - total net operating surplus relative to total capital stock

Source: Dick Forslund, "Profits, ‘productivity' & wage bargaining" (AIDC)

These tables all spell out a basic narrative - since 1994 profits have increased but the resulting surplus has not generally been ploughed back either into inclusive, developmental investment in growth or into wages. Another way of putting this is that since 1994 the medium-term strategic agenda of South African monopoly capital has largely prevailed over the strategy of using the democratic breakthrough as a platform to advance a second phase of the NDR.

This is not to say that transforming the balance of class forces is now irreversible - and, indeed, important shifts in policy and practice have been occurring over the past decade, and especially since 2009. However, in some ways the altered domestic balance of forces now makes the task more difficult than it might have been in the mid-1990s with South African monopoly capital still strategically off balance in the light of the new political reality.

The power of South African monopoly capital and mistaken policy choices by government, particularly in the period 1996 to around 2003, have meant that it is monopoly capital that has positioned itself to be the main beneficiary of the democratic breakthrough of 1994. But it is not just a question of who has benefited most. Benefits translate into class power, and class power translates into the ability to dominate; the capacity to subvert and undercut transformational endeavours; to influence and infiltrate our own formations; and the resources and arrogance to wage an unceasing ideological onslaught against progressive, state-led policies.

How GEAR policies favoured monopoly capital's disinvestment agenda

The NDP envisages raising investment levels from 16% of GDP (2012) to 30% plus by 2030 - (a 30% level was achieved in the 1980s). But the NDP fails to say how (apart from proposing the utopian idea of a social pact), because it fails to diagnose why investment levels dropped badly after 1994. In effect this is because it is unwilling or unable to critique the GEAR macro-economic package and related policies. These all played straight into the hands of monopoly capital's agenda to disinvest out of SA through:

- The liberalisation of exchange controls;

- The allowing of dual listings to major SA monopolies (Anglo, De Beers, SA Breweries, SASOL, Old Mutual, Liberty, Billiton, etc.);

- Which was exacerbated by allowing foreign operators where we already have major domestic operators (Edcon, Top TV, Walmart), resulting in further expatriation of dividends;

- Too high an exchange rate versus a more competitive Rand (which effectively enhanced the value of Randdenominated assets taken abroad, at the expense of our manufacturing and agricultural sector);

- Too high a level of interest rates at the expense of domestic investment (to attract short-term inflow transfusions, "hot money", to compensate for the haemorrhaging impact of capital flight).

In addition to all of the above, there has also been massive illegal capital flight and insufficiently effective regulation of transfer pricing, particularly in the mining and construction sectors. As a consequence, it is estimated that some 20-25% of GDP has been disinvested since 1994.

Financialisation - the growth of the casino economy at the expense of jobcreating productive investment

Related to all of the above, nurtured by and further contributing to it has been the dramatic "financialisation" of the commanding heights of the economy.

"Financialisation" refers, in the first place, to the growing dominance of banks, insurance companies, retirement funds and other financial institutions relative to other sectors of the economy.

Since 1994 the financial sector in SA has increased by some 300% compared to 67% for the rest of the economy. The NDP and Goldman Sachs praise this growth, but what does it actually mean? It means, as Professor Ben Fine puts it, "some three times the amount of financial assets had become necessary to support the production of a unit of output." While the financial sector has ballooned in size, the relative importance of manufacturing and mining has diminished.

The "contribution of mining and manufacturing to GDP has fallen to 23% from 38% in 1986" (Goldman Sachs).

However, "financialisation" does not just refer to the ballooning of the financial sector as such, it also refers to the way in which key productive sectors themselves are increasingly dominated by "share-holder value", nominal "financial worth", as opposed to other economic and social values. This results in all kinds of other perverse outcomes - the disposal of less profitable mines, in order to cherry-pick the most profitable regardless of the impact on jobs or productive output; company buy-backs of their own shares in order to artificially prime the share value; the payment of senior management in shares in order to incentivise short-term dividend returns, rather than long-haul productive investment.

The rapid and dramatic financialisation of the South African economy since 1994 has seen the value of the JSE relative to actual productive output in our economy ballooning. The Goldman Sachs report notes approvingly that "South Africa is a standout among all countries covered, with an equity market capitalisation that is twice the size of GDP".

Financialisation - the example of Afrgri

Afgri is an agricultural services company that dates back 90 years. It was originally an agricultural co-op set up to assist white family farms. It was handsomely supported by successive white minority governments with subsidies and other assistance. After 1994, instead of transforming this cooperative to service emerging and subsistence farmers, government liberalised agriculture. Like other former agricultural co-ops (KWV, Clover, Senwes) it transformed itself into a private company and listed on the JSE in 1996. Former cooperative members now became share-holders, free to trade their inherited shares on the stockmarket.

Financial speculation and profit maximisation began to displace agricultural production and food security concerns.

Today, Afgri remains a major player in our agricultural sector, and therefore, in theory, also a key asset in ensuring rural transformation and South African food security. It owns a vast proportion of South Africa's grain storage capacity, it provides services to 7 000 mainly commercial farmers through its ruralbased retail outlets and silos. It is the largest supplier of John Deere tractors in Africa and was recently subsidised through governments' tractor support programme for emerging farmers. Afgri also acts as an agent for the Land Bank distributing some R2-billion a year on behalf of the bank.

Afgri has recently been in the financial news with the proposed next, enAFRICAN COMMUNIST | December 2013 14 tirely predictable and dangerous step into further speculative financialisation.

The senior management are now intending to de-list the company and sell it for R2,6-billion to a private, largely unknown investment company, Agri- Groupe Holdings, which is registered in the tax-haven of Mauritius. 70% of its share-holders are reportedly North American. Although all of this has been covered in the financial pages of the media, there has been very little political outcry up to this point.

However the African Farmers' Association of South Africa (Afasa), representing a claimed 30 000 black smallholder farmers, has endeavoured to raise the matter. It has called on government to prevent the sale and taken the matter to the Competition Commission, labelling the proposed sale as a "blatant stealing of a cheap asset built by the state and South African commercial farmers".

Afasa has correctly noted that Afgri is "a very important cog in the lives of farmers and rural communities in Mpumalanga, Gauteng, Free State and KwaZulu- Natal...This is a company at the very heart and soul of South African agriculture and has been so for a century." Unfortunately, the proposed sale of Afgri has also now served to further divide black farmer representative structures, with the National African Farmers' Union of South Africa (Nafu SA) coming out in "unequivocal support" for the move and in opposition to Afasa.

It is probable that the Nafu SA leadership has been offered shares in the new arrangement, with its president Motsepe Matlala appearing to take a very opportunist stance. He has been quoted as saying that "as far back as 1996 Nafu SA had taken a stance similar to Afasa's present one and lobbied against the deregulation of agriculture - when the agricultural co-operatives such as KWV became companies. We said you can't deregulate the industry with blacks on the outside. We still hold that view. But the then agriculture minister Thoko Didiza went to court and we lost the case. We had to move on and we are now at a time when moving on is even more important. We have laws in this country and you can't continue to invoke history when opposing progress." It is critical that the SACP supports Afasa and that we ensure that the deepening loss of sovereign control over our food value chain to speculative foreign domination is halted and reversed.

The unfolding Afgri case is an exemplary reminder that the disastrous impact of the 1996 class project continues to be at play. It is absolutely imperative that the SACP injects this kind of class analysis into the 20-years of democracy narrative. Without such a class analysis we will simply get a "things are better than they were" story line. It is a story line that, whatever its merits, will disarm us in seeking to chart out the way forward to advance, deepen and defend the NDR.

The dominance of monopoly capital has also been buttressed by its control and dominance of private commercial media, which has for years been on a sustained ideological offensive against the working class and the ANC-led government.

Part of this offensive has been on blaming government for all the ills of capitalism, including for effects of the predatory behavior of monopoly capital itself. In addition, there has been a sustained and continuous ideological attacks on the working class, blaming it for things like strikes and indebtedness as being responsible for lack of AFRICAN COMMUNIST | December 2013 15 investment and problems in our country.

For instance private capital's attack on government's credit listing amnesty was seeking to absolve the financial sector for its complicity and responsibility in working class indebtedness through reckless lending.

Towards the SACP Centenary

Using this ACC it is important that we begin to focus our programmes and activities towards the centenary of the SACP in 2021. But this focus must not just be about working towards a date in a calendar, focus on what kind of SACP and what kind of South Africa would we like to see by that time, essentially 8 years from now. This is particularly not a long period, but will be characterised by a number of milestones in which the SACP must contribute towards shaping the outcomes.

2014 marks 20 years after the democratic breakthrough. Incidentally, the correctness of our characterisation of 1994 as a democratic breakthrough is being affirmed by the very notion of the necessity to inaugurate and drive a second phase of our transition. The 1994 first democratic elections marked a democratic breakthrough rather than an achievement of a substantively democratic South Africa at the time. It was a deliberate characterisation on our part signalling the fact that whilst 1994 inaugurated a historically and qualitatively new era in our country, lots of struggles still lay ahead to achieve the kind of South Africa envisioned in the Freedom Charter.

The fact that only now we are talking about a more radical second phase means that much as a lot has been achieved - and indeed the ANC is correct in its observation that South Africa is a much better place than it was in 1994 - a lot still has to be done. The notion of a second phase certainly does not mean that a lot has still to be done through ‘business as usual' (and certainly not through ‘business unusual' as well), but that we will need decisive breaks and ruptures with parts of the trajectory we have pursued, especially during the first 16 or 17 years since the democratic breakthrough.

2014 we are also holding the fourth national democratic elections. It is therefore also a year during which we must reflect on the past 20 years and map a way forward, and in our instance using our centenary as an important milestone and measure going forward.

This ACC must discuss and adopt key elements of our programme of action for 2014, but a programme of action that must be contextualised within, and also lay a basis for sustained SACP work towards 2021.

Between 2014 and 2021, 2017 becomes very significant in the wake of our own 14th Congress and the 54th Conference of the ANC. In both these congresses it is likely that there will be significant changes in the leadership across our Alliance structures, thus laying a basis for a different leadership for government after the 2019 elections.

Our actions and campaigns from next year onwards must prefigure and seek to shape the kind of leadership and priorities for the 2017 congresses and beyond.

We must begin to reflect on the challenges for 2017 at this very ACC.

Prior to 2017 we will be holding our Special Congress in 2015. This special congress must, amongst other matters, receive and adopt a report on the organisational renewal and restructuring of the SACP. But much more importantly the Special Congress must not AFRICAN COMMUNIST | December 2013 16 only receive a report on the SACP and state power, but must assess the entirety of our Medium Term Vision of building working class hegemony in all key sites of power and fronts of struggle. Much as the issue of the SACP and state power is most fundamental, this needs to be related to the broader question of power in society as a whole.

The year 2017 also marks the centenary of the Great October Socialist Revolution. From now onwards we must begin to prepare for this centenary as it is an important platform to intensify socialist propaganda in the broader South African society, and also tell the story of the relationship between the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and the struggles for national liberation and socialism, both in our country and in the rest of the world. It would be important to produce some publications for this centenary, including both the negative and positive lessons from the 1917 revolution and its aftermath.

2019, two years before the SACP's centenary, will mark the holding of the 5th democratic elections, and the inauguration of a government whose new leadership would have been elected in 2017. It would indeed have to be a government that will reflect the extent of the influence of the SACP and its socialist values, as well as the extent to which the power of the working class would have had an influence in society.

The forward march to 2021 starts now, with the preparations towards the 2014 elections and the 2014 SACP programme of action being the major platforms to start this march in earnest.

The SACP's 2014 programme of action

It is important that we ground our 2014 programme of action on an assessment of the state of each of our Alliance components and the tasks that arise out of this for the SACP in particular.

The state of the ANC branches and the effectiveness of these structures in our communities is relatively weak. In some areas there is indeed a very real danger of implosion within our structures, and the Alliance is often weakest at this level. In fact the functionality of our Alliance structures at branch level must be assessed against the background of the relationships and functionality between the ANC and SACP structures. It is also against this background that we must also reflect on the strengths, weaknesses and functionality of the SACP's VD based branches and the extent to which they are providing leadership in community struggles and people's effective participation in governance at a local level.

Whilst the ANC and SACP branch structures tend to do some commendable work during the elections, this work is however always complicated by internal battles around nominations, especially during the local government election campaigns. These structures are unable to have any sustained programmes of mobilisation for effective driving of governance beyond the elections The anchor of the 2014 Programme of Action must be the revival of the "Know Your Neighbourhood" Campaign (KYNC), especially to capacitate our branch structures to undertake this work in communities, including a proper grasp and understanding of priority governance and local development issues.

Our political education and capacity building for our branches must prioritise the understanding of the locality and the mobilisation of communities to drive local development programmes and projects. In a number of our areas both our districts and branches must also be empowered to actively participate in the many infrastructure development projects being rolled out by government.

The second key component of our 2014 Programme of Action must be the revitalisation of the financial sector campaign, building on the organisational and campaign work done during the 2013 Red October Campaign. Through this campaign the SACP must aim to build a mass movement aimed at the socialisation of the financial sector, as a platform for intensifying the critique of capitalism and its financial system as well as building the much needed community organisation and mobilisation.

Key components of the campaign must include:

- Criminalisation of the perpetrators of irregular garnishee orders.

- Criminalisation of law firms acting as debt collectors - they have no such powers in law

- Tighter regulation of micro-lenders.

- Action against the SASSA service provider which is illegally marketing air-time and other "services" at pension pay-out points, preying on the vulnerable.

- The socialisation of worker retirement funds - especially those nominally controlled by trade unions. These funds have been captured by private sector pension fund managers and have become a key factor in the growth of business unionism, and the related factional battles within Cosatu.

- The launch of the Postbank.

- The roll-out of FLISP (the government- guaranteed provision of bonds for the gap housing market). Despite being announced by government, Treasury has failed to provide the promised backup guarantee and the banks (who are not excited by the idea in the first place) have used this as a reason to boycott the proposal.

The financial sector campaign must be intensified as our flagship campaign towards the centenary of the SACP, and as a primary platform around which to build mass organisation and campaigning at local level. Our districts must be appropriately capacitated and resourced to be able to lead this campaign. The SACP must develop a political education programme and materials to capacitate our local leadership. Whilst it is important for Marxist-Leninist classics to be studied by our local structures, these in themselves without accessing and developing contemporary Marxist knowledge on the financial sector, will not empower our Cdes on tackling current challenges.

The challenges facing the progressive trade union movement: the need for focused and sustained SACP and Cosatu activism

It is also within this context that we must clearly define the tasks of the working class moving forward. It is important that we face the reality that the working class is currently faced with an extremely challenging period, especially the very real threat of a significant breakaway from our ally, Cosatu.

During the course of this year the SACP has been undertaking extensive analyses and discussions on the challenges facing the trade union movement, especially our ally, Cosatu. We have come to the principal conclusion that the challenges facing the trade union movement must not be approached from the standpoint of personalities, but through a careful analysis of the material and objective conditions facing the trade union movement, and as the basis for understanding the unions' own subjective strengths, weaknesses and responses to its challenges.

The objective primary sources of the challenges facing the trade union movement are a combination of the impact of the current global capitalist crisis as well as the advances and offensive by monopoly capital as captured in the first part of this political report. Whilst the global crisis might have worsened, the challenges facing the labour movement, critical in the South African reality is the economic dominance of monopoly capital over the past twenty years, including the reversal of some of the gains made by the trade union movement since 1994.

However, within the above context, what we have not adequately analysed are some of the specificities of the tensions that have erupted within Cosatu over the past few years, but especially over the last year. What we might not have properly grasped is the extent to which Cosatu has been contested internally (and indeed from outside) by a combination of forces, combining a variety of contradictory forces of workerism, business unionism and aspirations to use the trade union movement to access political power outside of, and in opposition to, the national liberation movement.

The primary target of this offensive has once more been the SACP. The SACP has always been the principal target of all the anti-Congress traditions, especially those breaking away from within our broad movement, from the PAC, to Inkatha, the Group of 8 and Cope.

Even inside our movement conservative strands like the 1996 Class Project and the New Tendency had all prioritised the SACP as its target - to seek to discredit and displace it, if not to drive it out of the alliance.

The latest factionalist surge from within Numsa has also placed the SACP as its primary target, in the same way as the 1970s workerist tradition had done in FOSATU, and later Cosatu. The primary reason for this is that a strong SACP has always acted as a counter to any workerist, or other claimed leftist pretences. The factionalist putsch by Numsa has become more intense, especially in the light of a more united SACP, whose prestige and influence in broader society and government policies has grown significantly after Polokwane.

In fact the Numsa-led opposition to the SACP participation in government had nothing to do with strengthening the SACP outside of government, but was about minimising the influence of the SACP especially on the state. Coupled with this was to keep the SACP highly dependent on trade union resources, in a manner that it could be controlled and be reduced into some union-controlled, oppositionist extra-parliamentary NGO type organisation.

What is the essence of the phenomenon we are seeing expressed through Numsa to try and capture Cosatu and redirect it into a political base for individuals and a faction within Cosatu? This tendency had sought to use Cosatu as its political base, position it gradually as part of some independent "civil society" than part of the liberation movement, building on the personal popularity of one Cosatu leader. This faction has been seeking to build its alternative base inside Cosatu by siding and supporting some of the renegade (and breakaway) elements in some of the key Cosatu affiliates (in NUM, SATAWU, POPCRU, etc).

Its strategy has also been to challenge the authority and standing of the ANC through championing itself as the primary fighter against corruption. Whilst using this left rhetoric, its primary source of influence has been business interests associated with some of the union investment vehicles, which also coincides with some of the personal accumulation interests within this tendency.

There is a coalition of a broader range of forces and interests both within and outside Numsa. The dominant tendency within the leadership of Numsa is firmly rooted in business unionism (hence its close links to EFF), backed by an old existing workerist tendency now working closely with formations like WASP. The latter sees an opportunity to achieve both inside and outside Numsa what it had always want to achieve, to drive a wedge between Cosatu and the ANC/SACP. But even more dangerous is that all these elements are showing a willingness to work towards a worker coalition with Nactu, Amcu and other splinters from Cosatu unions, including disgruntled elements within the federation.

Whilst these trends do not share the same political strategy or political goals, their interests converge around either capturing Cosatu or splitting from it, using Numsa as the nucleus of an alternative federation.

It was the response to this agenda by this tendency within Cosatu that led to the reaction by the leadership of Cosatu, immediately sparking the ‘political process' and the subsequent problems.

There are two primary tasks in the immediate future to (re)unite Cosatu.

The first is the need for Cosatu to remobilise but re-focus, away from programmes that have been defined by the factionalist tendency trying to capture Cosatu (e-tolls, etc), into focusing on the capitalist class as the principal enemy of South Africa's working class at the moment, as underlined by the earlier analysis in this report.

We need to move Cosatu away from narrow oppositionism into confidently leading struggles around a living and a social wage, transformation of the workplace, and also working closely with the SACP on the transformation of the financial sector, as part of reclaiming worker influence over their funds and resources. Internally Cosatu needs to focus on confronting the cult of the personality through, amongst other ways, revitalising a campaign to service membership led by the affiliates' presidents.

The second task for the SACP is that of intensifying its work with and inside the trade union movement. Whilst in the past we had committed ourselves to doing this, we have not created the necessary internal structures to focus on this task. Perhaps, we need to revive the Trade Union Commission as a substructure of the CC, together with the establishment of a well-resourced trade union desk in the SACP.

Such a commission and desk should not only be reacting to problems in the trade union movement, or just only in Cosatu, but creatively work with the trade union movement as part of building what we have referred to as an independent, militant trade union movement but that is part of the Congress movement.

This document first appeared in the SACP journal the African Communist, December 2013 (see here - PDF)

Click here to sign up to receive our free daily headline email newsletter