This is the fourth article in a series on the history of post-apartheid violent crime. The previous three articles can be read here:

The nightmare from which we have yet to awake (I)

Introduction

The previous article in this series described the trends in violent crime following South Africa’s political miracle of 1994. The number of recorded deaths directly linked to political violence fell dramatically after the 27th April 1994 elections, which ushered in both majority rule and three decades of one-party dominance under the African National Congress.

The total number of reported homicides stabilised at around 25 000 per year through the Presidency of Nelson Mandela, before entering into a long and consistent trend of year-on-year declines. It initially appeared as if the violent predatory criminality that had surged during the transition would follow a similar trajectory – with the number of robberies stabilising between 1994 and 1996.

There was, however, a striking inflection point in 1997. This was the year that the ANC publicly abandoned racial reconciliation in favour of transformation, and accelerated its quiet purge of the state machinery. Over the next several years there would be consistent year-on-year increases in the number of robberies under aggravated circumstances recorded, as the upwards trend first manifested in 1989 was reactivated.

The observation that post-apartheid South Africa was horrifically blighted by such criminality would be banal, were it not so contested today by Western intellectuals. Indeed, this peculiar tendency mars otherwise deeply researched and insightful accounts of post-apartheid South Africa. As noted in the previous article, in The Inheritors Eve Fairbanks presses the clearly erroneous claim that “By the end of the ‘90s, the police were recording only half as many incidents of crime as they did in the early ‘90s, despite a population growth of nearly 40 percent.” In his recent book on the 2019 elections, as played out in Mogale City, Evan Lieberman claims a “serious mismatch between trends in crime, including violent crime (which has largely gone down), and perceptions and fears of crime and violence (which continue to go up) during the post-Apartheid period.”

Both authors also put a racial spin on their assertions. Lieberman states that “compared with the extent of crime and violence that Black Africans face, the reality for White South Africans is one of relative security.” Fairbanks suggests to her American readers that the common fear by many whites of having their homes invaded by criminals were, in part, a guilt-ridden “fantasy”. She cites one source to suggest both that “a number of white South Africans had a memory of being assaulted in their homes when it never happened” and that “’the safest parts of South Africa’—formerly white urban suburbs—remained ‘as safe as anywhere in Western Europe’.”

Where though does this insistence come from that South African, and particularly white South African, fears and experiences of violent crime post-apartheid are unwarranted if not completely delusional?

Murder as a false proxy

The root of the confusion is basically this: When South Africans speak of their fear of violent crime they are referring, above all, to aggravated robbery. This is a crime where, by definition, the victims are accosted on the street, in their vehicles, in their businesses, or (most terrifyingly) in their homes, and threatened (or worse) with death or grievous bodily harm by their assailants.

There is a common tendency to assume that the incidence of homicide serves as an adequate proxy measure for this type of criminal violence. But while the homicide rate may well be the best measure for tracking overall violence in countries across the world - due to the issue of under-reporting of other categories of crime - robbery related murders tend to make up only a relatively small share of the total. Home-robbery related murders tend to be, in turn, only a fraction of these.

To use an international example to illustrate the point, according to figures released by the Federal Bureau of Investigation there were 413 402 robberies reported in the United States in 2003. These were responsible for 1 056 out of 14 408 homicides that year. A further 93 homicides were burglary related, and another thirty, motor vehicle theft related. 1 600 homicides were the result of gang and drug-related violence. The bulk, 4 334, stemmed from interpersonal conflicts and fights, with the circumstances unknown in 4 891 cases. In 915 of these latter cases (and 43% overall) the victims and perpetrators were however known to each other. The perpetrators were confirmed as strangers in only 12,5% of all cases, with the relationship unknown in 44% of cases. Even with robbery murders, in 24% of cases victim and perpetrator were acquainted with each other.

What this indicates is that the bulk of homicides are usually the result of interpersonal or inter-criminal violence. Robbery-related murders tend to make up a small proportion of all homicides and stem from a very small proportion of all robberies. Yet it is such killings, and other less common forms of stranger-murder, that people fear the most, and so think of first when figures for the number of murders are mentioned. This quite natural response creates a cascade of misperceptions.

Clearly, to begin with, the absence of murder does not mean an absence of aggravated robbery and vice versa. When it comes to trends, if these conflict then a small decline in the number of deaths resulting from dominant causative factors – such as interpersonal and political violence in South Africa of the 1990s - can offset even a large increase in deaths resulting from a smaller subcategory, such as robbery-related killings.

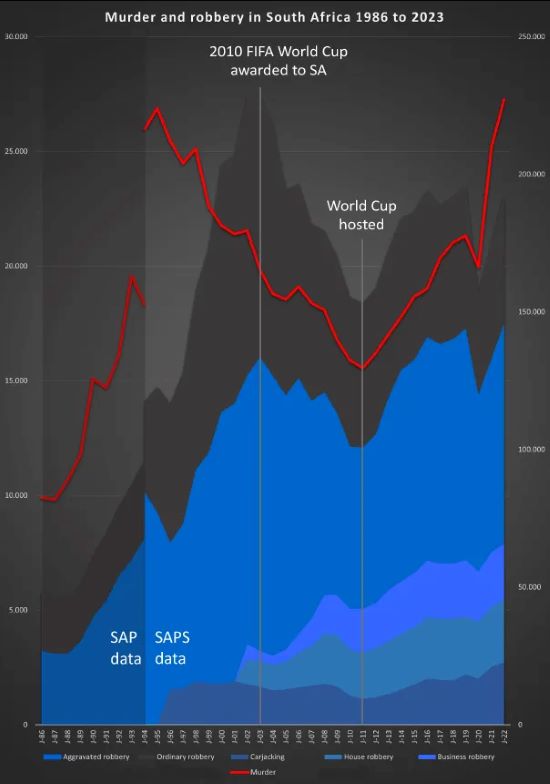

One of the great problems in making sense of violent crime in South Africa post-1994, and how it affected different communities, is that we do not have the sort of detailed data of the sort that the FBI compiled and published, including of the demographics of the victims. Nonetheless, it is clear from the crime statistics that are available (see our updated murder and robbery graph) that between the mid-to-late 1990s and the mid-2000s the number of homicides and the number of aggravated robberies trended in opposite directions.

The 2000s were generally a period of highly positive social and economic developments for the ANC’s constituency, which was finally able to reap some of the long-delayed rewards of liberation. Fuelled by the commodities boom economic growth reached 5%, unemployment declined, and government was able to massively increase the sum spent on social grants and public servant salaries. The avenues for self-enrichment of the ANC political class were also greatly widened in this period – through cadre deployment, Black Economic Empowerment, and tenderpreneurship - with the bill for these institutionally and economically destructive policies only falling due several years later. Firearms also became less easily available, which helped to reduce the deadliness of ongoing violence.

In the 1998/9 to 2003/4 period the number of reported homicides declined from 25 127 to 19 824. The fall was particularly dramatic in townships like Soweto and Katlehong, areas which had been notorious for their high murder rates under apartheid, and which had been at the centre of the political violence over the last decade of white rule. In Soweto 471 murders were recorded in 2003/4, a third of the number (1 391) reported in 1984. In Katlehong and the adjacent township of Vosloorus 219 murders were reported in 2003/4, again only about a third of the number (601) reported in Katlehong alone in 1984.

In this same 1998/9 to 2003/4 period, however, the number of aggravated robberies recorded rose from 92 630 to 133 658, a 44% increase. The dismantling of the police’s specialised units by ANC police chief Jackie Selebi, and the continued exodus of skilled professionals to the private sector, resulted in an implosion of the capacity of the detective services to identify and apprehend suspects.

This meant that in many middle-class areas once served by the now disbanded murder-and-robbery units hardened criminals could go on violent crime sprees that would last for years before they were finally ended. In one infamous case Ananias Mathe, a former Frelimo soldier, embarked on a murder, robbery, and rape spree in the northern suburbs of Johannesburg in 1999. He would only finally be taken off the streets seven years later (after one last dramatic escape from a maximum-security prison) after being arrested, prosecuted, and finally convicted of 64 out of 71 crimes that he could be linked to – including murder, attempted murder, numerous rapes of women in their homes, hijackings, and other assorted armed robberies.

The initial response of terrified suburbanites to such crime was to barricade themselves in their houses behind high walls and install panic buttons to summon armed responders at the moment their assailants burst in. Though these measures created the illusion of impressive security they were of doubtful value. They left criminals free to cruise through these areas unobserved and unimpeded and meant they had little fear of being disturbed once they had breached perimeter security.

In poor township areas the expensive security measures employed in the suburbs were inconceivable. But this does not mean that the community-based responses to crime in these areas were less effective, as many intellectuals often assume. In her memoir of growing up as a “born free” Malaika Wa Azania describes how she and her mother Dipuo –who are also the two main subjects of Fairbanks’ book – moved to Braamfischerville in the mid-2000s, an RDP housing estate next to Meadowlands, Soweto, which fell under the Dobsonville police precinct.

In response to rampant crime in the area a satellite police station was set up and street committees were formed to patrol at key hours. Every household was required to have a whistle, and when an intruder was spotted, the blowing of the whistle would alert their neighbours. The neighbours would, in turn, blow their whistles, until the entire community was summoned to the scene. Malaika observes, “The criminal would then be immobilised through a non-fatal beating. The police would be called and the suspect incarcerated. The introduction of this system saw a dramatic decrease in criminal activity in the neighbourhood. The people had won the war against crime.”

In the rural areas meanwhile, between 1998/99 and 2003/4 759 people were murdered in 5 406 attacks on farms and small holdings, according to figures compiled by the SAPS. In February 2003 the ANC government set about phasing out the commando system in these areas, the most important line of defence for farming communities. The purpose of this was to disarm ‘the boers’ ahead of a future drive to seize their farmland. President Thabo Mbeki nonetheless assured parliament that the purpose was actually to “ensure security for all in the rural areas including the farmers”. The promise was that the commandos would be replaced by “a revised SAPS reservist system”.

A footballing miracle

For fifteen years, from 1989 to 2003/4, the number of aggravated robberies reported every year had been on a relentless upward march, at which point this halted, and for several years headed back down again. This remarkable turnaround can largely be put down to FIFA’s announcement in May 2004 that South Africa would host the football World Cup in June-July 2010.

South Africa’s high levels of violent crime were one of the main threats to the successful hosting of this event and it was at around this time too that the Mbeki Presidency finally started taking the issue more seriously. Tony Heard writes in his memoir on his time in the Presidency that “crime was increasingly discussed at the advisory forum in the Presidency. I noticed how earlier nonchalance that crime was ‘not so bad’ and mainly just a white or elite perception, changed to all embracing concern.” In the ANC’s January 8th statements in the run up to the competition there were repeated exhortations to the party faithful to join the fight against crime, and the police were given political backing to deal with street criminals.

Yet even in these years venal ANC interests, and the movement’s ideological and political imperatives, continued to trump the desperate need for effective crime fighting institutions. Thousands of former lower-level MK cadres were given sinecures in the police service. In line with ANC racial doctrine Selebi obsessively sought to enforce the doctrine of “demographic representivity” at all levels of the SAPS. This required the effective abolition of the merit system and closing off the career paths of many able and committed police officers, on the basis they were white or Indian and therefore ‘over-represented’. Legal efforts to challenge Selebi’s prioritisation of race proportionality over all other considerations had some success in the lower courts, but they were ultimately squashed by the comrade judges of the Constitutional Court.

The one state institution still able to prosecute high level crime and corruption was the Directorate of Special Operations (DSO), or “Scorpions”, which had been set up in 1999 as part of the newly established National Prosecuting Authority. But this offended both factions of an increasingly divided ANC by asserting its independence and pursuing corruption cases against both ANC Deputy President Jacob Zuma and Selebi himself in 2007, and the DSO was abolished by a unanimous vote of the ANC caucus in parliament the following year. It was replaced by the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation (DPCI), or “Hawks”, which fell under the command of a more easily controlled and directed police service.

However, for a few years in the run up to the World Cup the police enjoyed the political backing to clear thugs off the streets. The number of aggravated robberies were brought down to 101 039 in 2010/11, the year the World Cup was hosted, mainly through the reduction in the number of street robberies. The number of car hijackings fell to a post-1994 low of 10 541 and the number of farm attacks too seem to have fallen considerably. The number of murders reported in Soweto in this year fell to 308 and the number of aggravated robberies to 2 777, not all that far above the 2 515 cases of armed robbery reported in the township in 1986.

There was a smaller dip in the number of residential robberies recorded – from 18 438 in 2009/10 to 16 889 in 2010/11 – and no decrease at all the in the number of business robberies. The number of reported homicides also reached their lowest point post-1994, with 15 893 murders recorded by the SAPS.

After the event

After the World Cup ended the fight against crime once again slipped down the list of the ANC government’s priorities, and other imperatives started asserting themselves again. The ANC now sought to wind down the successful reservist system within the SAPS, which had offset to some degree the earlier exodus of critical skills from the police. The number of police reservists stood at 63 592 in 2010. By 2014 the number had been cut by more than two-thirds to 18 577, before they were phased out almost completely. The ruling class made sure that they themselves were increasingly well protected. The total amount spent on VIP protection services – the armed guards of the ANC political elite – increased from R216 million in 1997/8 to R2,15bn in 2014/15, a close to three-fold increase in expenditure in real terms.

Up until 2014 there were still some redoubts of integrity and professionalism with the state’s investigative structures, particularly within the South African Revenue Service, but also in the Hawks and the Independent Police Investigative Directorate. As the country hurtled towards kleptocracy in 2014 these institutions were purged of key officials, many of whom had MK backgrounds and some of whom had even supported Zuma’s challenge to Mbeki. President Jacob Zuma would increasingly govern by placing weak, corrupt, or compromised individuals – “the worse the better” - in key positions in the police, prosecution, intelligence structures, and elsewhere.

The ethos within the ordinary police had, by 2014/15, become increasingly corrupt across the board. In another notorious case, one of the senior ‘old guard’ officers still in the SAPS, Colonel Christian Prinsloo, was involved in the sale of thousands of confiscated weapons in police stores to gangs in the Western Cape between 2008 and 2015. Thanks again to Selebi’s dismantling of the police’s anti-corruption unit in 2002, it was several years – and hundreds of gangland killings later - before he and his accomplices were eventually brought to book.

All the institutional checks against organised criminality and state corruption had been flattened by this point by successive ANC administrations. There were thus no guardrails left to check the plunder of state-owned enterprises, to protect suburbanites from armed gangs, or to stem the flood of hard drugs into the country.

In regard to the latter it was already evident in the mid-1990s that South Africa was becoming a major hub for international drug traffickers, and a growing market for hard drugs such as cocaine - which had been kept out of the country through the apartheid period. It was noted in a March 1996 SAPS report that 136 drug syndicates were operating in and from South Africa. This report also commented that the initial restructuring of the SAPS had already led to a decline in the ability of the police to counter trafficking by increasingly wealthy and sophisticated drug syndicates – something later vividly described by Johann van Loggerenberg in his account of his time as a deep cover police agent.

It was reportedly in 2004, the year after Selebi’s final closure of South Africa’s anti-drug police agency, that cheap black tar heroin started flowing into the country from Afghanistan. It was dubbed Nyaope in the townships and its use, usually in adulterated form, was noted in press reports from Pretoria in 2008. A hard drug epidemic, involving both Nyaope and ‘tik’ (methamphetamine), would spread unchecked across township areas across the country in the years following the World Cup. The drug trade and drug addiction helped drive a resurgence of criminality, as gangs battled it out to defend their turf, and the young men hooked on these drugs desperately sought to feed their addictions by preying on their neighbours and even close family members.

The source of the error

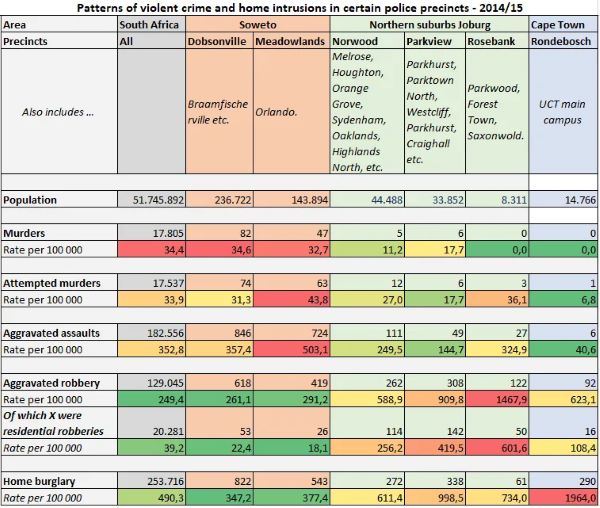

According to the SAPS crime statistics residential and business robberies were already up to record numbers in 2014/15, at 20 281 and 19 170 incidents respectively. There had been a surge in truck and car hijackings as well, and overall, the number of aggravated robberies reported were back up to 129 045, just short of the previous 2003/4 peak. The 17 805 murders recorded in 2014/15 were, however, still far below the highs of the mid-to-late-1990s.

The following year the criminologists Anine Kriegler and Mark Shaw published their book A Citizen’s Guide to Crime Trends in South Africa. It celebrated the fact that the number of murders had fallen so dramatically and the murder-rate even more so. Kriegler and Shaw wrote that in 2014/5 the SAPS had recorded fewer than 18 000 murders, down from 27 000 recorded twenty years previously in 1994, “in a population that has grown since then by about 40 per cent”, meaning the murder rate had more than halved. This half-remembered fact is clearly the origin of Fairbank’s fallacious crime around the incidents (or rates) of crime halving in the 1990s.

Kriegler and Shaw also comment in their book on the “perplexing” inconsistency between victims of crime surveys and the SAPS crime statistics on the matter of home robberies. For instance, in the 2014/15 survey, conducted by StatsSA, the respondents claimed to have reported around three times as many “home robberies” to the police, as “residential robberies” recorded by the SAPS in the national crime statistics.

For Fairbanks this disparity was “so stark” it suggested to her that a “number of white South Africans had a memory of being assaulted in their homes when it never happened. On some level, I found white South Africans simply expected to have their homes invaded someday by black burglars…. Perhaps the survey respondents heard frightening reports of home invasions on the news and came to imagine the memory was theirs. But some of the respondents may have imagined they had been attacked in their homes simply because they could not understand how they would not be.”

This would be truly remarkable, if at all true, but Kriegler and Shaw themselves did not make any racial distinction; and nor could they, as the same apparent disparity is evident in the replies of black, Coloured, and Indian respondents as well. (The police also do not release figures on crime victimisation by race.) The phenomenon is, in other words, unrelated to the race of the respondents.

It is likely to be accounted for, in good part, by the much narrower definition used in SAPS’ crime reporting than in the StatsSA survey. In the police statistics residential robberies are a subcategory of aggravated robbery, which usually means armed robbery. For the StatsSA survey there only needs to be some form of “contact” between victims and perpetrators during a break in for it to be classed as a “home robbery” - “’home robbery’ is regarded as a violent crime because people are at home when it takes place as compared to ‘housebreaking’ (burglary), which occurs when the family is away from home.” It is likely then that many of the home intrusions mentioned to StatsSA by survey respondents were classified by the police as common robberies and/or burglaries.

Kriegler and Shaw are also the source for Fairbanks’ claim, again in the context of white fears of aggravated robbery, that “‘the safest parts of South Africa’—formerly white urban suburbs—remained ‘as safe as anywhere in Western Europe’” after 1994. Referring to the 2014/2015 SAPS crime statistics the criminologists stated that “There are some parts of South African cities that have murder rates on par with some of the safest places in the world. Murder rates in suburbs like Rondebosch in Cape Town and Rosebank in Johannesburg would cause no concern if they were found in cities in Western Europe or Canada…. The safest parts of South Africa are as safe as anywhere in the world.”

The reason Kriegler and Shaw referenced these two police precincts were that there were no murders reported in either of them in 2014/15. It is obviously not possible to have a murder rate below zero. That does not mean they were “safe” by either Western European or even South African standards when it came to violent crime in general, and armed robbery in particular.

The police precinct of Rosebank in Johannesburg covers a former residential area in Johannesburg turned into an elite business node, in the heart of the city’s verdant northern suburbs. Its office parks, malls, and office buildings draw in a great number of people commuting to work every day. It also encompasses some suburban areas and had an estimated residential population of 8 311 in 2014/15. It lies between the Parkview (33 852 residents) and Norwood police precincts (44 488 residents). These three precincts cover areas – Houghton, Saxonwold, Forest Town, ‘the Parks’ - which are the quintessential ‘leafy suburbs’ of old northern Johannesburg.

If you look at police figures for 2014/15 it is evident that, while no murders were recorded in Rosebank there had been a dramatic surge of residential robberies in this area and its surrounds. In the three precincts of Rosebank (50), Norwood (117) and Parkview (142) - 306 residential robberies were reported in 2014/15, up from 222 the year before - a rate of 353 per 100 000 residents. (There were 11 murders committed overall, giving a murder rate of 12,7 per 100 000 residents.)

The Rondebosch police precinct meanwhile covers a similarly middle-class, mostly residential area in Cape Town, and includes the campus of the University of Cape Town. Its population was estimated at 14 766 in 2014/15. Sixteen residential robberies were recorded in the area in 2014/15, a rate of 108 per 100 000 residents. This precinct, though less affected by residential robberies, had a proportionally greater number of aggravated street robberies, as well as house burglaries, than its Joburg counterparts.

How do these residential robbery rates then compare with “anywhere” in Western Europe? Well Germany, for one, recorded 784 aggravated robberies of people in their homes in 2014 - a rate of 1 per 100 000 residents. This means that the rate in Norwood/Rosebank/Parkview police precincts was some 350 times higher, and in Rondebosch over 100 times higher. The suggestion that such “formerly white urban suburbs” remained as safe post-apartheid as anywhere in Western Europe is thus out by two orders of magnitude and beyond.

The residents of these famously middle-class suburban areas were also highly at risk, on this measure, relative to South Africa as a whole. The residential robbery rate nationally in 2014/15 was 37,1 per 100 000 residents in 2014/15 - and was lower still in the Dobsonville (22,3) and Meadowlands police precincts (18,1) in Soweto where Malaika and Dipuo grew up. The levels of interpersonal and vigilante violence in these areas were clearly far higher than in the suburbs, and the resultant incidents of murder (or more accurately, manslaughter) pushed up the murder rate to close to the national average.

The apartheid pattern endured in the sense that unsettled urban areas, particularly ones which had experienced a huge influx of recent migrants, exhibited incredibly high numbers of assaults, street robberies, and homicides. But in Johannesburg the old apartheid-era order whereby the residents of the leafy northern suburbs were protected from the armed thugs who terrorised the residents of the townships had been turned on its head.

Reopening of the frontier

The puzzle presented by Kriegler and Shaw in their book was why the “plummeting” murder rate was not being widely celebrated. “How is it that this huge reduction in fatal violence over the last two decades isn’t something we rejoice over, talk about or even seem to be aware of as a nation?” The answer to this was not impossibly complicated. South Africans’ anxiety around violent crime was driven, firstly, by fear of aggravated robbery, and particularly home robbery. By the time the book was written these forms of crime, which had never gone away, were already surging back upwards. Secondly, a pervasive sense of physical insecurity was further compounded by the ineffective police response to crime.

Over the years it became ever clearer to different communities that they could not rely upon the state to defend them from predation. The response this took in middle class suburban and farming areas was a reliance on increasingly sophisticated private security. In poorer areas this manifested itself in vigilante justice with criminals caught in the act being subjected to brutal on the spot punishment. In well-organised and defended communities’ crime could be kept at bay. It would be those living in or traversing the borderlands – such as elderly people living alone – who would be at the most acute risk of predation.

At best the police retreated into a clerical role, taking criminals into custody who had been apprehended by others, and registering case numbers for theft and robbery victims for insurance purposes. At worse they themselves crossed over into outright criminality. Although this is likely just the tip of the iceberg, given low detection rates, in the four years between 2019/20 and 2022/23, 5 489 police members were arrested for various criminal offences. According to a parliamentary reply by the Minister of Police to Pieter Groenewald, MP, 383 of these cases were for serious crimes - 220 for murder, 195 for robbery, 110 for rape, 29 for livestock theft, and four for cash-in-transit heists.

This brave new world was brought into sharp focus during the July 2021 insurrection in KwaZulu-Natal and parts of Gauteng, unleashed in response to former President Jacob Zuma’s brief imprisonment. SAPS members stepped down, while it was left to communities to organise themselves to defend their neighbourhoods from looting and violent destruction.

After a dip occasioned by lockdown and curfew measures implemented during the Covid-19 pandemic period the number of reported murders surged from 19.972 in 2020/21 to 25 181 in 2021/22 and increased again to 27 272 in 2022/3, the highest number ever-recorded. Last year also saw record numbers of aggravated robberies (145 934), car jackings (22 742), and residential robberies (23 029) reported.

According to the SAPS a causative factor could be established in 10 876 of the homicides in 2022/3. About half of these could be attributed to various forms of interpersonal violence. 802 were identified as gang-related and 318 as taxi-related.

1 670 were robbery related (including the 202 murders linked to hijackings). To put that number in some kind of perspective there were 31 cases of theft or robbery related murders in England & Wales in 2021/22, and in 19 of those cases the victims knew the suspect. Most extraordinarily, 2 124 homicides were put down by the police to vigilantism and mob-justice, up from 1 202 counted in 2019/20.

It is these two figures in particular – for mob justice killings and robbery-murders – which encapsulate the degree to which popular confidence in the criminal justice system has collapsed alongside the state’s ability to protect the population from violent predation.

This article first appeared on the Konsequent substack.