INTRODUCTION

On October 17 2018 Judge Ronnie Hendricks convicted Phillip Schutte and Pieter Doorewaard of murdering Mathlomola Jonas Moshoeu, a teenager caught stealing sunflower heads on their employer’s farm near Coligny, as well kidnapping and intimidating Bendel Pakisi, the state’s sole eyewitness in the case,.

In early March this year Hendricks proceeded to sentence the two “white farmers”, as the New York Times described them, to 18 and 23 years in prison respectively.

The two are now known around the world as the Sunflower or Coligny murderers.

Hendricks revoked Doorewaard and Schutte’s bail on conviction, and the two have now been sitting in jail for almost six months. They still do not know whether Hendricks will grant their application for leave to appeal, and remain uncertain as to the outcome of their efforts to overturn their conviction.

This article is the third in a series of special reports on this extraordinary case.

In the first article, Rian Malan introduced readers to Bendel Pakisi, an informal sector butcher who claimed to have seem Doorewaard & Schutte repeatedly hurling Moshoeu off the back of their bakkie, inflicting fatal injuries. Pakisi’s eye-witness account of this “despicable” racist crime provoked widespread arson and looting, but when the case came to trial he changed critical aspects of his narrative and repeatedly contradicted himself.

In the second, Gabriel Crouse addressed the forensic evidence, said by Hendricks to corroborate Pakisi’s horrifying narrative. On closer inspection, this claim turned out to be unsustainable.

Today, in this third article, we examine the call data from Doorewaard & Schutte’s cellphone activity on the morning of Moshoeu’s death, and its significance. Anyone who reads crime novels knows that cellphone technology has radically transformed the business of solving crime. It’s not just that police can “grab” your calls and listen to your conversations. If you own an advanced smartphone and its geolocation or geo-positioning function is working, they can pinpoint your exact position and trace any journey you have made.

Making calls from an ancient Nokia can land you in trouble too. You say, I was home in bed when the bank was robbed. Police say, sorry lad, your phone records show you were ten miles away, making and receiving calls that registered on a cellphone tower overlooking the bank where the robbery took place. Cellphone technology can work the other way, too, providing alibis to prove one’s innocence.

Such cellphone location data would potentially be critical to solving the sunflower murder case. All the leading actors in the drama claimed to have been carrying Vodacom cellphones on the morning of the alleged crime. The curious history of Pakisi’s phone is dealt with in footnote [2] below. Here we focus on the four devices belonging to Doorewaard and Schutte. In court, the two Afrikaners rejected Pakisi’s account in its entirety, claiming they’d never even seen him before, let alone taken him on a two-hour hell ride to lonely places where he could be terrorized and intimidated without anyone seeing. So, in theory at least, cellphone location data could be dispositive.

Given the public importance of this case, and the critical nature of this particular evidence to it, it is necessary to lay out the evidence in three separate parts. The question we will seek to answer is a simple one: are Doorewaard & Schutte guilty of the crimes for which they were convicted?

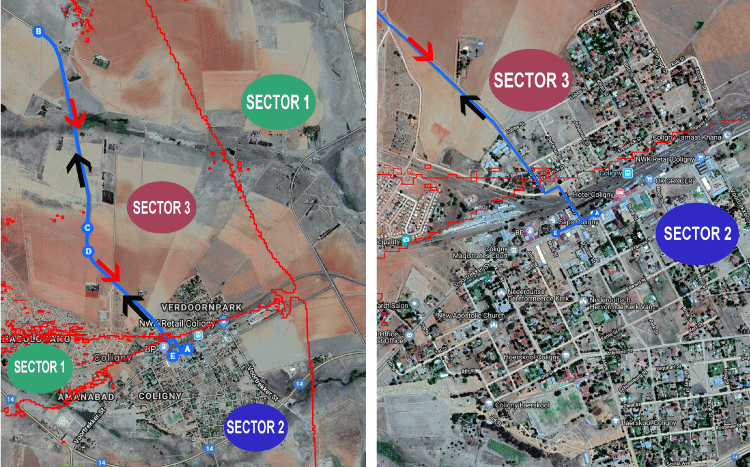

In Part 1 we map out the two different and wholly incompatible versions of what happened that morning. A depicts the version presented by the accused at their bail April 2017 bail hearing and during their trial. B depicts one of the versions presented by sole witness Pakisi.

In Part 2 we introduce the cellphone location data that was presented to court by Vodacom’s forensic experts.

In Part 3 we examine what that data says about the validity of these two incompatible versions.

PART 1: A TALE OF TWO JOURNEYS

A. Doorewaard and Schutte’s account

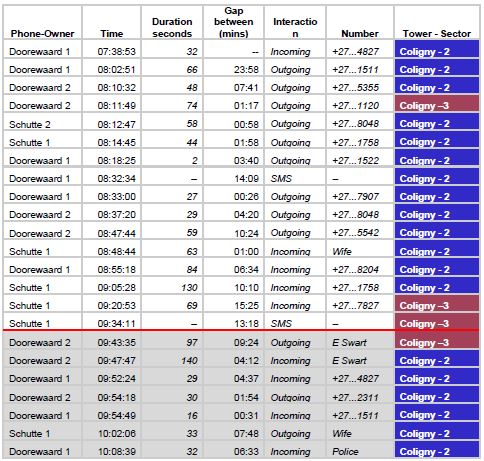

Doorewaard & Schutte’s account of the fateful day begins at 7am, when they reported for work at their employer’s workshop in Coligny. They claimed they remained at the workshop until just after 9am, when they headed off to collect samples from a peanut field a five minute (5km) drive from town in a north westerly direction. See below.

On their way back at around 9.30am they said they saw two teenagers stealing sunflower heads in a field belonging to their employer. They apprehended one, Moshoeu, and told him to get in the back of the bakkie. After a brief period driving back and forth looking for his accomplice, they headed towards town to report Moshoeu at the police station.

As they approached a bend in the road, Doorewaard and Schutte notice that Moshoeu was no longer on the back of their bakkie. They testified in court that they assumed he had jumped off, although they did not actually see this happen. On turning back they found him lying motionless in the road, bleeding. Reluctant to move Moshoeu for fear of aggravating his injuries, they asked two passers-by to watch over him while they rushed into town to report the accident at the police station, and get the SAPS to summon an ambulance from Lichtenburg.

Map 1: Doorewaard & Schutte’s version

There was little dispute that Moshoeu’s fall occurred at around 9.35am to 9.40am, and that Doorewaard & Schutte reported the incident to police very shortly afterwards. There was also no question about the location of where Moshoeu lay (D), as this was confirmed by numerous independent witnesses.

B. Pakisi’s account

Pakisi’s version of events was radically different. According to his court testimony, he was walking past the sunflower field towards Scotland informal sector at around 7.10 am that morning when he heard a gunshot. In the sequence of events that followed he said he saw Schutte repeatedly throwing Moshoeu off the back of a moving bakkie driven by Doorewaard. There was a mysterious and as yet unidentified third man in the passenger seat. When the whites realized Pakisi was watching, Schutte drove up to him on a quad bike and ordered him, at gun point, to return with him to the bakkie. This episode lasted between “15 and 20 minutes”, Pakisi said in one of his later statements to police.

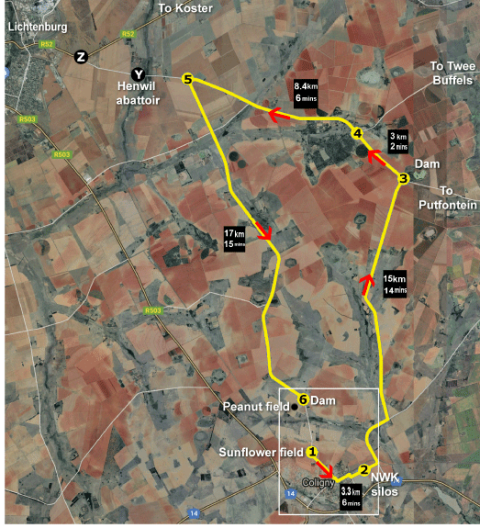

He was then forced onto the back of the bakkie, where an injured and unconscious Moshoeu would lie throughout the subsequent journey. The party then headed off in convoy in the direction of Coligny, stopping 700 metres down the road to deposit the quad bike at a farm gate. Schutte then got onto the load bed of the bakkie, which drove through Coligny to the NWK silos on the other side of town. They would probably have reached the silos at around quarter to eight. Here Pakisi was interrogated about what he had witnessed and subjected to a brutal assault. The party climbed back on the bakkie and set off on on the next leg of their journey.

Map 2: Pakisi’s version at trial

They then drove fifteen kilometers (14 minutes) to the north before stopping at the Lichtenburg-Putfontein T-junction (3). Here Pakisi was subjected to an even longer ordeal. He was forced to drink Captain Morgan rum, as well as one of the Castle Lights he had with him, then told to jump over the fence and walk into the water of a dam about 200m away from the road. Here he desperately begged Schutte not to kill him. After the third man came and told them there were people nearby, the accused and their captive returned to the bakkie, where Pakisi was made to drink from the rum bottle before setting off again.

Next stop was the Twee Buffels junction, roughly 3km (or 2 mins) further on. Here, Pakisi was ordered off the bakkie and told to run along the gravel road while his tormentors fired shots at his heels. Pakisi ran until he collapsed from exhaustion and fell down vomiting.

After that, the party drove just over 8km (6 mins) on the tar road towards Lichtenburg, halting again at the Coligny turn off (5). Here Pakisi was again forced to run in front of the bakkie while the accused fired shots at him. Again, he ran until he collapsed and started vomiting. This time, the accused forced him to eat his own vomit.

They then drove off towards Coligny in a southerly direction before eventually stopping next to a dam (6). Here Pakisi was ordered to wipe up blood from the back of the bakkie, give over his address, and hand over his cellphone, a Nokia Xpress. The whites then knocked him out and when he came around hours later, they were gone.

After ruling that Pakisi was a truthful and honest witness, Judge Hendricks filled in the final gap in his story. The “only reasonable inference”, Hendricks declared, was that Doorewaard & Schutte drove on towards Coligny after clubbing Pakisi unconscious and then dumped the dying Moshoeu at the spot where he was later found lying motionless and bleeding. As noted earlier, this would have been between 9.35am to 9.40am.

Although there were significant changes through Pakisi’s different versions [1] the basic shape of his journey remained more-or-less consistent. After forcing him onto the back of their bakkie, his captors travelled in an anti-clockwise loop out to the north-east, then to the west, and then back to the south. The journey would have begun at around 7.30 in the morning, and ended some two hours later. A significant part of this time would have been spent driving, as the distance between from Point 1 to Point 6 is 47km, often on untarred roads. A journey of this distance would take roughly 45 minutes at legal speeds, without any breaks.

As can be seen from the white rectangle on Map 2, there is a very limited overlap between these rival accounts in terms of time and place. Simply put, Doorewaard & Schutte claimed to have been in Coligny town throughout most of the period when Pakisi claimed they were in outlying rural areas, trying to intimidate him into keeping his mouth shut.

PART 2: THE CELLPHONE LOCATION EVIDENCE

Clearly, then one side or the other was lying about where they had been and what happened in the critical 7 am to 9.30 am time frame. Here cellphone location data could help unlock the entire case. In court, Doorewaard & Schutte testified that they were both carrying two Vodacom cellphones that morning, one mainly for work and the other for personal purposes. There were 16 transactions on these four phones – 14 calls and 2 SMS’s- between 7.38am and 9.34 am that morning.

During bail proceedings the previous year Brigadier Clifford Kgorane, who was the driving the investigation, testified that Section 205 subpoenas in terms of the Criminal Procedure Act were being used to secure relevant cellphone records and coverage maps. These were however not produced by the State during discovery, nor presented by the National Prosecuting Authority during trial. .

Instead, it fell to Doorewaard & Schutte’s defence team to approach Vodacom for this information, and to call expert witnesses to explain it. First up in the High Court in Mmabatho on the 3rd September 2018 was Vodacom’s Lynette Van Zyl, who presented detailed records of all activity on the accused’s four phones that morning. She explained that records from Vodacom’s electronic archive are infallible. They are generated by machines, and cannot be altered or adjusted by human intervention. They are, said Van Zyl, “99.99 percent accurate.”

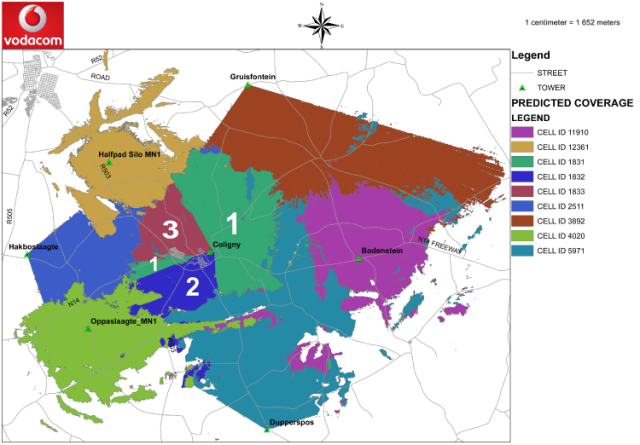

Next up was Samuel Hallatt, another forensic expert working for Vodacom, who presented a map showing the location of Vodacom’s transmission towers and their coverage footprints. Hallatt explained that most cellphone towers in the country are “sectorised” meaning that “they are split up into different antennas covering different sections. These sectors also add up to 360 degrees.” The Coligny tower itself was broken up into three sectors.

Hallatt testified that every time there was a “transaction” on any given phone– a call connecting or an SMS being sent or received – Vodacom’s system would record not just which tower picked up the call, but in which sector of that tower it fell as well. There was a 20 meter overlap between coverage areas where calls could go either way.

Hallatt explained how information from Doorewaard & Schutte’s phones fitted in to the map below. The darker green patches, for instance, represent the areas covered by Sector 1 of the Coligny tower. Dark blue is the area covered by Sector 2 of the Coligny tower and its allied antennae. Maroon shows the area covered by Sector 3 of Coligny tower, again with its allied antennae. Yellow represents the area covered by Halfpad Silo tower, and brown by the Gruisfontein tower. And so on. The white areas are all covered by other towers or antennae not shown on this map.

Map 3: Vodacom coverage map of Coligny and surrounds

Note: Labels 1,2 and 3 added by Politicsweb.

During cross examination by Advocate Moeketsi for the prosecution, Hallett stated that the system picked up and recorded in which area the start of a call had occurred, but not where it terminated. If no transaction took place, the Vodacom data could not tell where the device’s owner was between calls. Is it possible, Moeketsi asked, that a person could make a call in Coligny, leave and come back without being detected? “Yes,” said Hallett.

At more or less this point, Judge Hendricks stepped in with some questions of his own. “A specific tower records when a call is made but not when it ends?,” he asks. “That is correct,” says Hallett. So if I make a call at Coligny that continues while I drive past other towers, your data will only reflect the call made in Coligny? “Yes,” says Hallett. Finally, Judge Hendricks poses a hypothetical: if I give you my phone and you stay in Coligny making calls on it, those calls will register in Coligny even though I wasn’t there? “Yes,” says Hallett. “That is correct.”

Exactly what this proves is hard to say, because police introduced no evidence to suggest that Doorewaard & Schutte had left their phones with someone in Coligny that morning. If they had done so, the defence was positioned to call the humans involved to testify that they actually spoke to Doorewaard or Schutte that morning. “We could easily have done that,” says Doorewaard’s counsel, Adv. Hennie du Plessis, “but it didn’t seem necessary because the state never questioned the veracity of the Vodacom records.”

To sum up then, every transaction on those four phones that morning registered with a particular sector of a particular tower. This placed the device, at that moment, in the coloured area allotted to that sector on the map. The state did not no dispute that Doorewaard & Schutte had all four devices in their possession at the times these transactions took place.

PART 3: TESTING THE TWO ACCOUNTS

With this established it is now possible to test the radically conflicting accounts of Pakisi and Doorewaard & Schutte against Vodacom’s records. The table below is a compilation of the relevant data for Doorewaard & Schutte’s cellphone activity on the fateful morning. The Tower ID column on the far right identifies the precise device that picked up the transaction. ID 1832, for instance, is Sector 2 of Vodacom’s Coligny tower. ID 1835 is an additional antenna on Sector 2 of the same tower. All transactions relayed by Sector 2 are coloured dark blue for ease of reference. Calls relayed by Sector 3 and its additional antenna are shown in maroon.

Table 1: Vodacom data for Schutte and Doorwaard’s calls of the early morning of Thursday, 20th April 2017

The average length of calls before Moshoeu’s fatal injury is 56 seconds, with the longest call being 2 minutes 10. The first call recorded is at 7.38 am, after which there is a 23 minute gap. From 8.03 am to 9.34 am there are 14 transactions recorded on the four phones. The average average gap between them 6 mins 30 seconds. The longest gap is 15 mins 25 seconds.

With the exception of one maroon outlier, all transactions prior to 9.05 occur within Sector 2 (dark blue) of the Coligny tower area. The transactions pass from the dark blue sector (9.05 am) to the maroon sector (9.20am, 9,34am, 9,43am) and then back to the dark blue sector from 9.47am onwards. In other words, at the moment each transaction occurred Doorewaard and Schutte were in either the maroon or dark blue sectors.

Pakisi Revisited

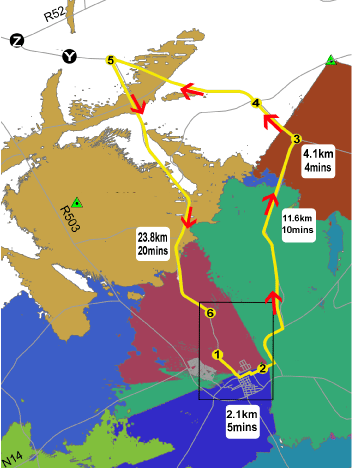

Let’s now lay Pakisi’s journey over Vodacom’s coverage map. As shown below, the route Pakisi claims to have followed during his kidnap ordeal crosses cellphone coverage areas in the following order: maroon -> dark blue -> dark green -> brown -> yellow/white -> maroon, as he and his captors moved in an anti-clockwise loop from Coligny to a point near Lichtenburg and back again.

Pakisi’s alleged ordeal began in the sunflower field, which falls within the maroon area reflecting Sector 3 of the Coligny tower. This is early in the morning, at a time when there were no cellphone transactions recorded. At around half past seven, according to Pakisi, his assailants drove through the very top of Sector 2 (dark blue) of the Coligny tower coverage area, and stopped at NWK silos (2), which lies right at the edge of that sector.

Doorewaard’s call at 7.38 am is thus potentially consistent with Pakisi’s version, but beyond that point everything changes. If Pakisi’s account is true. Doerewaard’s next call at 8.02am would have to be within either Zone 1 of Coligny tower (dark green) or Sector 2 of the Gruisfontein tower (brown). It is not. It is also within the dark blue area.

Map 4: Pakisi’s route overlayed on the Vodacom map

1: Sunflower fields. 2: NWK Silos. 3: Lichtenburg-Putfontein T-Junction. 4. Twee-Buffels T-junction. 5. Coligny T-Junction. 6: Dam.

At around 8 am Doorewaard and Schutte’s bakkie leaves Sector 2 of the Coligny tower zone and drives for 11,6km through the dark green zone. No transactions are recorded in this sector. It then crosses into the area covered by the Gruisfontein tower (brown). This is where the protracted incident at the dam (3) allegedly occurred. No transactions are recorded by Vodacom here either.

After that, the accused and their captive crossed into the white/yellow zones representing the footprints of either Halfpad Silo tower or towers not shown on this map. This is where both running and shooting (4) (5) incidents allegedly took place. The distance from the start of the white/yellow areas, to the point where the party cross back into Sector 3 (maroon) is 23,8km or a 20 minute drive without stopping. No transactions recorded by Vodacom here either.

Just more than 84% of the journey, in terms of distance, occurs in the dark green, brown and white/yellow areas; 75% in terms of driving time. The longest stops, according to Pakisi’s description, take place at points 3, 4, and 5, along the Lichtenburg-Putfontein road to the north. Conservatively then one can say that about an hour-and-twenty-minutes of his two hour long hell ride would have taken place in these areas. The traversal of these areas also takes place slap bang in the middle of the journey, and would have to fall across the 8am to 9am period. Not a single transaction however is recorded in the green, brown or white/yellow coverage areas.

Finally, a call by Schutte at 9.20am places that cellphone in the maroon of Sector 2. This is potentially consistent with Pakisi’s version, as they would have had to be back in the maroon zone at around this time. To support Pakisi’s account however the previous call at 9.05am would have been in the yellow/white zone. It is not. Again, it fell within the dark blue zone.

And Doorewaard & Schutte

Let us now turn to Doorewaard & Schutte’s account, and see whether the table above fits their version of what happened that morning. The map below overlays their version of their fateful journey upon the different Coligny tower coverage areas. The red lines mark precisely the dividing line between sectors. Most of Coligny town is covered by Sector 2 (dark blue), while the Verdoonpark neighbourhood to the north of the railway line falls in Sector 3 (maroon). The Tlhabologang township falls across Sector 1 (dark green) and Sector 3 (maroon.)

On the day in question they commence work around 7am, at the workshop (A) which is located in the town’s business district. This is in the dark blue zone. The 13 cellphone transactions recorded in Sector 2 between 7.38 am and 9.05 am all place them in this area. Initially Schutte is carrying two cellphones – one for work and one private. At 8.12am he uses the work phone to make a call, after which its battery goes dead. He puts it on charge, at his home, before they head out to the peanut field.

Map 5: Doorewaard and Schutte’s route overlaid onto the Vodacom coverage map

A: Workshop. B: Peanut fields. C: Sunflower fields. D: Place where Moshoeu fell. E: Police station.

As they drive out of town they cross into Sector 3 (maroon), at a point slightly beyond the railway line. The next transaction (a call) at 9.20 am is in the maroon area, where both the peanut and sunflower fields are located. An SMS at 9.34 am also places them in this area. According to his plea explanation, immediately after leaving Moshoeu with the passers-by at point D Doorewaard calls a local attorney friend, Esme Swart, to ask her for the number for an ambulance. This transaction also registers in Sector 3 (maroon). The call ends at 9:45. Two and a half minutes later Swart calls back, by which time Doorewaard and Schutte are already at the police station (E). This call registers back in Sector 2 (dark blue), where the police station is located (E).

CONCLUSION

The Vodacom records thus support Doorewaard & Schutte’s account of what happened that morning, and completely contradict Pakisi’s version. In the 8 am to 9 am period there are 12 transactions which locate Doorewaard and Schutte in Sector 2 of the Coligny tower. This is 15km to 20km, as the crow flies, away from where Pakisi’s testimony placed them during this period. There is no way that Pakisi’s account can be reconciled with these cellphone location records. This data, in other words, is completely discrediting of Pakisi as a witness, and his account.

This all raises something of a puzzle.

Pakisi was the sole eyewitness in this case. His uncorroborated testimony was the only evidence the state could produce against the two accused. The Vodacom forensic evidence, set out above, shows that his account was a fabrication. Why then is he not facing perjury charges? Why was this case even brought to trial by the NPA? Why are Doorewaard & Schutte described in the local and international press as “murderers”? And most importantly, why are the two men currently sitting in jail for a series of crimes that they could not have committed?

The simple answer to all these questions is that Judge Hendricks decided that Pakisi’s testimony was “honest, truthful and reliable and must be accepted”, and convicted the two accused on that basis. In order to get to this determination Hendricks just skipped over the cellphone evidence.

In his judgment he dealt with the cellphone evidence in a perfunctory manner. He briefly summarised Van Zyl and Hallatt’s evidence. He then referred to Hallatt’s testimony that there had to be a “transaction” for location data to have been recorded. “The relevance of his evidence to this case” Hendricks said, “is that although both accused had their cellular phones in their possession, no information would be recorded unless a transaction took place at or near the specific tower or area, for example if one looks at the telephone records of the number 0828843193, said to be the cellphone belonging to accused 1 [Doorewaard], on 20 April 2017 there is a time lapse between 08:55 and 09:52 of almost an hour.” Hendricks just left the matter there, and did not refer to this evidence again.

It is not clear what exactly what Judge Hendricks was suggesting here, other than that this almost hour long gap was deeply significant. In reality, the 8.55 am call transaction placed Doorewaard in Sector 2 (dark blue) of Coligny town. That alone is incompatible with Pakisi’s account. Even if the bakkie had departed from NWK Silos at that moment, as Hendricks seems to be implying, it would still not be possible to fit the subsequent journey, as described, into the forty-five minutes or so before Moshoeu fell. In any event, there were five other calls recorded on the other two devices in the possession of Doorewaard & Schutte between 8.55am and 9.52am. If these other phones are included, the almost hour-long gap is cut up into 10, 15, 13, 9, and two 4 minute segments.

The lesson of this all? The Bill of Rights may say that every person has the right to a fair trial, but when the mob is hungry, even a rock solid alibi is not enough to secure an acquittal for those accused.

Footnotes:

[1] Pakisi changed his story significantly in the various statements given to police, and at trial, of which some changes are relevant here.

a.) In his first statement to Coligny police on the 23rd April 2017 he said that he had witnessed Moshoeu being thrown off the back of the bakkie at just after 9.10am in the morning. This would have meant that all the events he described, including 45 minutes of driving, occurred in under half an hour. After Schutte and Doorewaard had presented their version at their bail hearing, Pakisi produced a revised second statement on the 22 May 2017, moving back the start of the incident two hours. The events he described could now plausibly have happened, in this period, though it would still be a tight fit.

b.) In his 22 May 2017 statement he said that at the NWK silos Doorewaard & Schutte had got out the bakkie and communicated to the third man still inside the van, “after some few minutes they got back into the van”. There was no mention of an interrogation or assault.

c.) In his statements to the police and others on the 23rd of April 2017, then again in his 22nd May 2017 statement, Pakisi had said that they had driven all the way to the Lichtenburg-Koster T-junction (Z), then doubled back, before stopping outside Henwil abattoir (Y). It was here he was first made to run, while being shot at. This section of his journey was simply lopped off during the trial, with Pakisi disavowing even knowing where Henwil was.

[2] Pakisi’ sim card was, according to Vodacom, “last used on the 9 April 2017 and only again used from the 8 October 2017.” The handset last connected to the sim card, also on the 9th April 2017, was a Vodafone Smart Mini 7. Despite this information being available to him, Judge Hendricks convicted Doorewaard & Schutte of the theft of Pakisi’s “Nokia phone”, and sentenced them to a year in jail for this crime. The data for Pakisi’s other, MTN, cellphone number was not secured or presented to court. It perhaps could have identified where he was that morning.

___

FAIR. BUT FEARLESS.

If you appreciated this article, and would like to see more of this type of feature, please consider becoming a Politicsweb supporter here.