Earlier this week the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), South Africa’s state thinktank, presented a paper on the topic of “school segregation” in post-apartheid South Africa in an online seminar. The co-authors were Dr Rob Gruijters from Cambridge University’s Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre, Dr Benjamin Elbers, a post-doctoral student at Nuffield College, Oxford University, and Dr Vijay Reddy, a distinguished research specialist at the HSRC.

According to a Daily Maverick article on the seminar the study found that the student population of those schools that had been limited to the white population only under apartheid, was now 54,4% black African, 29,4% white, 12,5% Coloured and 3,6% Indian. Former black African schools in the townships and former homeland areas remained (almost) wholly black African with former Coloured and Indian schools presumably somewhere in between.

The findings in effect were that while South Africa’s racial minorities, and a minority of black Africans, now attend racially integrated schools, most black African pupils do not, for largely unavoidable demographic and geographical reasons.

The authors’ complaints about ongoing “segregation” were directed though not at the still monoracial black African schools but the now multiracial formerly white schools. Dr Gruijters’ told the seminar that “Former white schools are, on average, the most racially diverse, but they also contribute most to segregation, because white and Indian children remain strongly overrepresented in these schools, relative to their share of the population.”

This argument, that South Africa’s integrated schools are the ones contributing most to segregation, is on the face of it a confusing one. It is clarifying to recognize that what the authors of the paper have done is to keep the word “segregation” - with all its hard-earned negative connotations – but then excised its old apartheid-era meaning and inserted a new (and no doubt improved) one.

For the authors the desired and expected norm is that the racial proportions of schools conform to the racial population of the total (school going) population in South Africa; so, 87,2% black African, 7,5% Coloured, 3,8% white and 1,5% Indian. The more a school’s population deviates from that norm the more “segregated” it is, and the more it conforms to it the more “integrated” it is. A 100% black African school is thus less deviant and problematic than a 50% white one.

It seems then that what the authors are actually exercised by is not segregation per se but rather the “over-representation” of the white and Indian minority in certain schools, particularly those with the best performing pupils academically.

Dr Gruijters told the seminar that while “many, but not all, former white schools are now racially diverse to varying degrees, they are not representative of the population — mostly because white students remain overrepresented in these schools and black children, in particular, remain underrepresented in the country’s best schools”.

He added that, according to the authors’ research, “white students attended schools that were 68,5% white, even though white students only constituted 3,8% of the overall population of children who attended school in 2021”.

The problem of white and Indian over-representation was particularly striking when it came to the thirty most elite (high fee) government schools and the thirty most elite private schools in the country. White pupils monopolised 62% of the spaces in the elite public schools and 55% of the spaces in elite private schools. Indian pupils hogged 6% of spaces in the former and 13% in the latter. This is while black African pupils occupied only 20% of the spaces in elite public schools, and 27% of the spaces in elite private schools.

Based on these findings the authors castigated the white minority, along with other socioeconomically advantaged groups, for using the terms of the post-1994 settlement to “hoard” educational opportunities.

I

This research painted a worrying picture of overrepresentation by non-indigenous minorities in many of the country’s best schools, but what can be done about it? Fortunately, other nations have grappled with a similar question, and so there is little need to reinvent the wheel when formulating a solution.

A similar situation, for one, was once well documented in German higher schools in the early 1930s by racial researchers. The Institut zum Studium der Judenfrage, a leading Berlin based thinktank funded by the Ministry of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment, put out a report in 1936 dealing in part with this "problem". According to the 1925 census the population of Germany was 62 410 619, of whom 38 175 989 (61,2%) lived in Prussia. The Jewish population meanwhile was 564 379, of whom 71,7% (404 446) lived in Prussia. The Jewish population thus constituted a mere 1,1% of the population of Prussia, and 0,9% of the population of Germany as a whole.

In its report the Institute described the alarming racial imbalances that had developed in high schools across Prussia as of 1st May 1932. In the higher boys’ schools, the report stated, 3,1% of the pupils were Jewish, so three times the Jewish share of the total Prussian population. In Berlin alone the figure was 8%, in Hessen-Nassau 6,3%, in Lower Silesia 3,4%, and so on. Only in Sachsen and Schleswig-Holstein was the figure under 1%, and so under the 1,1% share of the Jewish population in the total population of Prussia.

The situation in the girls’ high schools in Prussia was even more extreme. The share of Jewish pupils in these schools was 10,4% in Berlin, in Hessen-Nassau 12,7%, in Lower Silesia 7%. It was only in Schleswig-Holstein that the proportion of Jewish pupils in the girls’ high schools was lower than the 1,1% Jewish share of the total Prussian population.

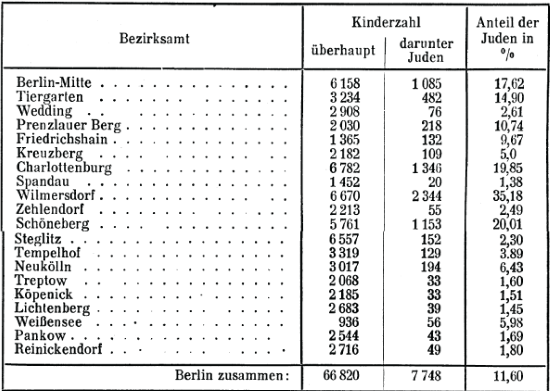

The report then highlighted the "dangerous" manner in which Jewish overrepresentation had developed in higher schools in the different administrative districts of Berlin. In not a single district in the nation’s capital, the report noted, was the share of Jewish pupils in these schools lower than the 1,1% Jewish share of the total population in Prussia. In ten districts it was even higher than the Jewish share (4,3%) of the overall Berlin population. The situation was worst in the wealthiest districts of the capital. In Wilmersdorf the share of Jewish students was 35.14%, in Schöneberg 20.01%, in Charlottenburg 19.85% and in Berlin-Mitte 17.62%. It set out these figures in the following table:

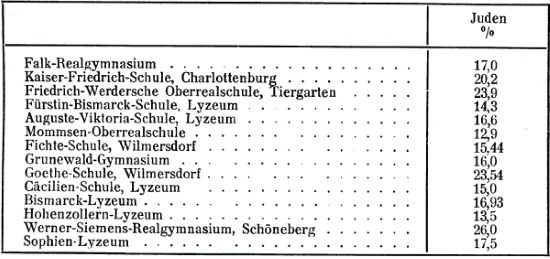

The Institute’s researchers then examined the demographic composition in fourteen of the most elite schools in the capital. In the following table they set out the "intolerable" situation of minority overrepresentation that had been allowed to develop:

Not unexpectedly, given these figures, a similar situation pertained in the universities of Berlin. In the Winter semester of 1932/1933 Jewish students made up 12,5% of students in the law faculty, 21,9% of the medical faculty, and 9% of the philosophy faculty.

II

By the time the Institute issued its report in 1936, listing these figures, this problem in Prussia had largely been addressed. It is instructive to examine precisely how this was done.

The national socialist movement in Germany had long been concerned by the way in which the Jewish minority had used the terms of the post-war democratic settlement in Germany to monopolise many of the best opportunities for itself. In late March 1933 mass demonstrations broke out across Germany calling inter alia for measures to limit the number of Jews in German secondary schools and institutions of higher education (as well as the professions) to their proportion of the total population.

The newly NSDAP government moved quickly to pass a law to give effect to this demand. The official rationale presented for the Law Against the Overcrowding of German Schools and Universities gazetted on 26 April 1933, was that the proportion of people of non-Aryan descent in the higher professions in Germany was “far greater than their proportion in the total population”. This imbalance was just as glaring as the reverse phenomenon, that the number of non-Aryans, especially Jews, who lived off manual labour was disproportionately small.

The situation gave those of foreign origin far too great an influence over German economic and spiritual life and weakened the German people and state. Above all, no self-respecting nation could allow its higher activities to be carried out by those of foreign origin to the extent that Germany had allowed up until then.

The admittance of those of foreign origin to the higher professions in a proportion too large in relation to their share of the population as a whole could, moreover, be interpreted as evidencing their racial superiority, something which was to be resolutely rejected. Given the intense competition for positions in the professions at the time it was also only natural and right that native Germans be given preference.

The predominance of those of foreign origin in the higher and more lucrative professions was largely due to their overrepresentation in the high schools and universities. It could not be expected for such people to limit themselves, of their own accord, to accessing educational opportunities in a manner concordant with the population ratio.

Therefore, by legally restricting the access of non-Aryans to schools and universities, the state would ensure that the correct proportions were maintained. This was also necessary to ensure that the German schools and universities preserved their German character.

In terms of the actual provisions of the law, as issued by decree, “the number of pupils and students admitted to each school and each department who are Reich citizens of non-Aryan descent [defined as someone with one or more Jewish grandparent] does not exceed the proportion of non-Aryans in the population of the German Reich. The proportion is determined uniformly for the entire territory of the Reich.”

The law also required that as the overall number of students in the universities an appropriate overall ratio “must be created between the total number of pupils and students and the number of non-Aryans. In the process, a ratio that differs from the quota can be taken as a basis”.

The former ratio was set by regulation at 1,5 out of a hundred for admissions, and for 5 out of a hundred for the overall ratio. In schools where the admission numbers were so low that accepting just one non-Aryan pupil would mean the permitted 1,5 per 100 quota was exceeded the school was allowed to admit a single non-Aryan pupil.

III

Could this sort of numerus clausus be introduced in South African schools to deal with the problem of racial inequity as exposed by the HSRC?

There is actually very little in the 1994 settlement to prevent any ANC (or future EFF) government from doing so. The ANC shrewdly engineered the equality clause in the final constitution of 1996 to allow it to enforce ‘demographic representivity’ in all fields of life, and at all levels, something it regards as a sacred objective of the National Democratic Revolution.

The fact that the ANC government has not done so in many schools is not because its hands have been tied in any meaningful way. Rather its attention has been directed elsewhere; mainly on enforcing race proportionality in the public service and state-owned enterprises, with the current focus being on senior and top management in the private sector. The different universities meanwhile have implemented a mishmash of race quotas on admissions in response to ANC demands.

The pupil (and staff) complements of high performing schools somehow slipped through the cracks and the HSRC, Nuffield College, and Cambridge University’s REAL Centre must be commended for bringing the attention of South Africa’s racial nationalists to this unpalatable fact. All that would be needed then is to now bring the racial principles that have already been applied to institutions like Eskom, the police, and the prosecution service, with such success, to those still high functioning public and private schools blighted by serious minority overrepresentation.

Here the German model could usefully be applied. This would require, in effect, that care to be taken to ensure that for every hundred students admitted to these schools only 3,8 should be white and 1,5 should be Indian. To ensure that there is no hoarding of opportunities on the margins the fourth white pupil admitted in a class of 100 should be 80% of average size, and the second Indian pupil would have to be even smaller still. In this way pupils of such ‘foreign origin’ would be kept in perfect conformity with the racial proportions of the total school going population.

The difficulties that may arise have considerably more to do with implementation. A certain ruthlessness would be necessary to push this policy all the way through. This relates both to overcoming minority resistance from without, as well as moral squeamishness from within. The experience of those few non-Aryans accepted into German schools, post the implementation of the April 1933 law, was not a particularly pleasant one.

A correspondent of The Times of London observed in 1936 that “owing to the 1,5 per cent regulation a Jewish or ‘part-Aryan’ child may be alone in its school, and the isolation from which it may suffer is very bitter. Part of the school curriculum consists of anti-Semitic diatribes, and the child is compelled to listen to the grossest and most shameful accusations levelled against its Jewish forebears. What must the effect on a ‘non-Aryan’ child be of being the object-lesson of such teaching?”

Life for such pupils was often so miserable, for these and other reasons, that a number of children “finding their life unsupportable, have sought the only means of escape open to them. There are others who have found within themselves the courage to endure. But many of the children share the state of mind of a little girl of 8 who said to her mother: ‘Pray to God that He will make me very ill or let me die. I cannot bear this any longer’.”

That racial equity policies may cause unavoidable distress to individual children is, of course, no reason not to pursue national social justice imperatives. It just requires of those implementing the policy a certain hardness. A more serious related problem is that if you apply a numerus clausus to one school racial minorities will tend to try and congregate in another. For this reason, it would be necessary to ensure that no school in the country be allowed to exceed the statutory limits on alien minority admissions and representation.

One inevitable result of enforcing such a policy across the board is that it would greatly accelerate the exodus of middle class white and Indian families from the country, given the high priority such families often place on their children’s education.

The resultant decline in the proportion of white and Indian children of school going age within South Africa would need to be closely and continually monitored, with the racial limits adjusted continually downwards, lest they inadvertently permit a situation to develop whereby such children were allowed to exceed, in any one school, their actual proportions of the school going population.

This is to be honest all a very complex, onerous and finicky undertaking, requiring eternal watchfulness, and it may ultimately be simplest to remove the last vestiges of segregation by kicking these alien racial minorities out of the school system, and then the country, altogether.