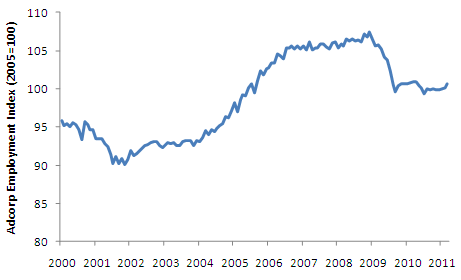

Adcorp Employment Index, March 2011

Salient features

- Employment put in a very strong showing during March, which was the first month since August 2008 - more than two and a half years ago - that all sectors, occupations and employment types recorded positive growth. The highest growth rates were recorded in agency employment (9.9%), in the transport (18.3%), electricity (13.6%) and mining (11.5%) sectors, and in agricultural (11.8%), professional (10.8%) and machine operator (10.4%) occupations. Total employment grew 5.6% during the month.

- Employment in the official sector grew 7.3%, while employment in the unofficial sector grew 2.0%, which is the first time since January 2006 that the formal sector drew workers out of informal employment.

- Temporary work grew by 3.7% during the month, of which agency work grew by 9.9% while non-agency temporary work declined.

- In this month's analysis, we take a closer look at the reasons for growth of temporary employment. Since January 2000, when Adcorp first compiled these statistics for South Africa, traditional permanent employment has declined by 20.9% (representing 1.9 million people) and temporary, contract and other forms of "atypical" employment has increased by 64.1% (representing 2.4 million people). In other words, all of South Africa's employment growth over the past decade - and then some - has been of a temporary nature.

Adcorp Employment Index

Source: Adcorp Holdings Limited

Analysis

One of the most extraordinary developments in international labour markets in recent years is the growth of temporary staffing. Since January 2000, when Adcorp first compiled these statistics for South Africa, traditional permanent employment has declined by 20.9% (representing 1.9 million people) and temporary, contract and other forms of "atypical" employment has increased by 64.1% (representing 2.4 million people).

In other words, all of South Africa's employment growth over the past decade - and then some - has been of a temporary nature. It is no doubt incorrect to use the term "temporary" to describe an enduring phenomenon that has been observed consistently for more than 25 years. Clearly there is nothing "temporary" about temporary employment, except in the limited sense that a particular temporary job may not last permanently or indefinitely.

Labour market groups have expressed differing views about employers' growing desire for temporary workers. To many trade unions, temporary work is a means by employers of circumventing labour laws and regulations, especially laws related to union organizing. To the UN agency responsible for overseeing international labour practices, the ILO, temporary work provides a much-needed stop-gap for people entering and exiting the permanent job market, such as youth, retired people, working mothers, and unskilled and inexperienced job-seekers.

To the international lobbying body for the temporary work industry, CIETT, temporary work is a natural business response to technological innovations in the workplace, such as 24/7 operations (which gives rise to shift work), management of peaks and troughs in business volumes (which gives rise to part-time work), and integrated supply chains (which gives rise to cross-company, cross-industry and cross-sector work opportunities).

There is no apparent agreement among these groups as to why employers' demand for temporary workers is rising. Even less, there is widespread disagreement about why an increasing number of job-seekers is proactively seeking out temporary work opportunities.

According to some commentators, chronic unemployment in heavily regulated (typically developed) labour markets has created a perpetual class of hopeless job-seekers, desperate for any work opportunity. To others, widespread unionization has created a sharp divide between "insiders" (who have access to medical aids, pension funds, and extensive legal protections) and "outsiders" (who cannot find work on any lawful terms). To yet others, the twin forces of globalization and technology adoption have created a "race to the bottom", where traditional, stable forms of work are giving way to precarious and unpredictable employment.

It seems incredible that 3.8 million South Africans - up from 1.4 million in 2000 - could be duped into accepting temporary work, if it were truly inferior. It is unbelievable that more than a quarter of the workforce has been fooled into giving up their apparently secure permanent jobs in favour of temporary work, if it were truly insecure. Given the sheer scale and consistency of the phenomenon, there must surely be something rational to at least some of the growing demand, among job-seekers, for flexible, part-time and temporary forms of work.

Some of the temporary work phenomenon is generational. In South Africa, the average age of a temporary worker is 27, whereas the average age of a permanent (and typically unionized) worker is 43. According to the Sloan Foundation, 85% of next-generation employees under the age of 30 actively seek part-time, flexible working arrangements - up from 22% just one generation ago. Increased parental and domestic responsibilities among males, in particular, have driven men to seek flexible work, which was long the domain of women. In South Africa today, more men than women (52%) are temporary workers, compared to a small minority (8%) a generation ago.

Another significant driver of the temporary work phenomenon is technological. Today work opportunities are heavily based on social networks, such as Facebook and LinkedIn, which have sharply increased workers' mobility between jobs. The average employee today will work for 8 different employers by retirement, up from 3 employers a decade ago. The flipside of job mobility from an employee's perspective is employee turnover from an employer's perspective, and in this sense many work opportunities are becoming "temporary" (i.e. of short duration) compared to a generation ago.

Much has been made about the possibly nefarious reasons why employers want to employ people temporarily, on limited-duration contracts. By contrast, very little is understood about the potential attractions of limited-duration work to the employees who, in growing measure, prefer to take on a succession of fixed-term, short-duration contracts with multiple employers. It may well be true that the phenomenon of a "job for life" is disappearing; but this appears to be driven at least as much by employees' changing preferences as by employers' desire to cut costs and boost productivity.

Temporary work is, in this sense, just one stage in the evolution of the modern workplace. It is an intermediate situation rather than the end game, where employees will be paid for their personal productivity, working probably reduced rather than extended hours. For ideological opponents of temporary work, it may seem implausible that a "willing buyer/willing seller" situation exists, and it is certainly more expedient to attribute sinister motives to businesses engaging in these practices. But the fact remains that a growing proportion of employment relationships is atypical, not only in South Africa but throughout the world.

Additional Data

Employment by Type

|

Occupation |

Employment Mar 2011 |

Percentage change vs. Feb 2010* |

|

Unofficial sector |

6,132,367 |

2.04 |

|

Official sector |

12,970,794 |

7.28 |

|

Typical (permanent, full-time) |

9,148,597 |

9.55 |

|

Atypical (temporary, part-time) |

3,822,197 |

3.70 |

|

- of which agencies |

994,226 |

9.94 |

|

Total |

19,103,161 |

5.57 |

* Annualized

Employment by Sector

|

Sector |

Employment Mar 2011 (000s) |

Percentage change vs. Feb 2011* |

|

Mining |

316 |

11.50 |

|

Manufacturing |

1,422 |

9.36 |

|

Electricity, gas and water supply |

89 |

13.64 |

|

Construction |

541 |

4.45 |

|

Wholesale and retail trade |

1,647 |

5.86 |

|

Transport, storage and communication |

532 |

18.32 |

|

Financial intermediation, insurance, real estate and business services |

1,604 |

3.75 |

|

Community, social and personal services |

2,619 |

4.14 |

* Annualized

Employment by Occupation

|

Occupation |

Employment Mar 2011 (000s) |

Percentage change vs. Feb 2011* |

|

Legislators, senior officials and managers |

1,021 |

3.54 |

|

Professionals |

675 |

10.76 |

|

Technical and associate professionals |

1,552 |

6.22 |

|

Clerks |

1,468 |

4.92 |

|

Service workers and shop and market sales workers |

1,806 |

0.66 |

|

Skilled agricultural and fishery workers |

103 |

11.76 |

|

Craft and related trades workers |

1,455 |

4.14 |

|

Plant and machine operators and assemblers |

1,047 |

10.40 |

|

Elementary occupation |

2,434 |

7.44 |

|

Domestic workers |

826 |

10.26 |

* Annualized

Statement issued by Adcorp, April 11 2011

Click here to sign up to receive our free daily headline email newsletter