On the early morning of Wednesday 25th October 2017, a group of armed men broke into the house of Joubert Conradie, 47, his wife Marlene, and their two children Hannes and Jana on their farm in Klapmuts outside Stellenbosch. When Joubert went to investigate he was shot and mortally wounded, dying soon after in hospital.

Later that day one of Conradie’s friends, Chris Loubser, posted an emotional video appeal on social media, calling for South Africans to wear black on Monday to mourn the victims of the ongoing farm murder epidemic in South Africa.

An event was then organised over a Facebook page – titled “Genoeg is genoeg” – in terms of which protesters would meet in Klapmuts and then drive in convoy through to Green Point Stadium in Cape Town. Similar events were also spontaneously and independently organised elsewhere in the country, many by AfriForum, with protesters sometimes blocking roads.

Across the country the protesters wore black clothes and carried white crosses, representing the almost three thousand people murdered in some twenty-to-thirty thousand farm attacks since the unbanning of the liberation movements in early 1990.

In the hundreds of images that were taken and circulated of the protests that day, there are all of four verified images of the Union Flag – the old South African national flag – two on clothing. There was an old man photographed on the back of a bakkie somewhere in Pretoria at a shopping mall, on the way to one of the protests. At a protest at a bridge over the R59 outside Vereeniging where the road had also been blocked, the Union Flag was photographed at a distance (so the image of the flag is tiny); it had been hung over the railings by unknown people. At the same protest one of the attendees wore a somewhat faded black t-shirt with an image of the flag, a noose, and the text “Gatvol for farm murders”.

These images were all taken in the early morning. Finally, a female biker from Kraaifontein was interviewed by a News24 journalist at or on her way to the Cape Town protest. She had the flag embroidered as a small patch on her leather biker’s waistcoat. When asked about it she said that she had felt safe under that flag. Asked why she hadn’t taken it off, given the organisers had said they didn’t want any apartheid-era memorabilia displayed at the protest, she said she wasn’t going cut it off “just for a meeting”.

Apart from that one example, there is no other recorded image of the flag being worn or displayed at either the Klapmuts/Cape Town or AfriForum protests. The R59 protest, where Die Stem was also sung by protesters, was one organised by persons unknown, not AfriForum. So why were there so many reports, and so much outrage on social media, over the old flag being extensively “waved” and “flown” at the protests?

Essentially this was the result of a cynical but clever influence operation being run on social media by people opposed to the protests and who were seeking to discredit them. Notably, the leading social media influencer and EFF activist Tumi Sole was seeking out and then circulating to his many followers any such images from early that morning. Other influencers also joined in, as did the DA and its leaders, which was seeking at the time to distance itself from its white support base.

There was little to work with after the early morning, and so old images of the Union Flag being displayed from years before started being used instead. In particular, it was the striking images of the old flag being very proudly displayed (or worn), set against the new flag being torched, which really ignited mass outrage nationally.

Flag images widely circulated on the day of the Black Monday protests. The juxtaposition of E against H, G and/or F provoked particular outrage on the day. All were all "fake". A, B, C, D are verified. C and B are from the same event.

These images were old ones, dating from years before. Yet through this process of selection, magnification, falsification and instant mass distribution via social media, the perception was successfully created by the end of that day that Black Monday protesters had been extensively flying the old flag across the country, while burning the new one.

Both the EFF and ANC then released statements denouncing the protesters as “racists” for displaying the “apartheid government flag”. Cabinet too condemned “the blocking of public roads, displaying of symbols of past oppression and destruction of national symbols which are a reflection of our hard-earned democracy.”

The reality though was that AfriForum and the organisers of the Klapmuts/Cape Town protests had prevented the use of the old flag at their events, to the extent that this was needed. The symbols employed were black clothes and white crosses. By contrast, it was the opponents of the protests who had deliberately circulated images of the old flag to stir up racial hatred and turn public opinion against the protesters and their cause. Not all the images used were “fake” but by far the most striking and powerful of them were.

In its statement issued a week after the protests on the 5th November 2017, the Nelson Mandela Foundation (“the Foundation”) declared that “apartheid was a crime against humanity” and “displaying the flag of apartheid South Africa represents support for that crime.” It denounced the “belligerence” of the protesters for “burning of the national flag” and “displaying of the old South African flag” and, after disparaging their cause, suggested that it was such “hubris” that underlay the “deep well of rage that underlies individual cases of murders on white-owned farms.” The insinuation was clearly that farm murder victims had somehow brought their horrific fate on themselves.

This statement also asked whether it was not time to “criminalise” displays of the Union Flag. Despite the basic premise of this statement being shown to be false – and many of the images it was referring to revealed as “fake” (most notably the flag-burning one) – the Foundation decided to press ahead, and in February 2018 it went to court to have “gratuitous” displays of the Union Flag declared hate speech, unfair racial discrimination, and harassment.

In his founding affidavit the Foundation’s CEO Sello Hatang again denounced the Black Monday protests as somehow being rooted in malign motives and accused the organisers and demonstrators of creating an enabling environment whereby individuals felt comfortable “not only bringing but brandishing the Old Flag, without any fear of ostracism by other demonstrators.”

Although he was forced to acknowledge by this point that some of the images were fake, he insisted that this did not matter, given that some of images were real, and these constituted an “unlawful celebration of a crime against humanity”.

In a case of seeking to prosecute Hamlet without charging the Prince, the Foundation could name no individual or organisation as a respondent who had either “brandished” the flag on Black Monday or condoned this in any way. Presumably had the Foundation found one of the four people who had displayed or worn the flag – and presuming they were not agents provocateurs – some individuals would have had to come to the Equality Court to explain, like the woman biker from Kraaifontein, that the old South African flag had positive connotations for them because life was better and more secure for them back then.

In the absence of any actual flag wavers, the Foundation sought to name AfriForum as the respondent, and that organisation then accepted its role as a “reluctant” respondent and chose to fight the case on narrow freedom of expression grounds. In prior debates with Hatang on the matter AfriForum’s Kallie Kriel had stated that while his organisation actively discouraged its members from bringing the flag to its meetings and events, he did not believe that the flag should be banned.

In August 2019 the Foundation, supported by the South African Human Rights Commission and the Minister of Justice, succeeded in their application to the Gauteng High Court, sitting as the Equality Court. Judge Mojapelo ruled that the display “of the Union Flag at the Black Monday protests” constituted “hate speech”, “unfair discrimination” and “harassment” in terms of the Equality Act, and that “any” display of the Union Flag, with certain exceptions when it came to journalism, academics and art, represented the same.

Earlier this year, when AfriForum sought to appeal the matter to the Supreme Court of Appeal, lawyers for the Nelson Mandela Foundation, the Minister of Justice, and the SAHRC unleashed, in their heads of argument, their heavy artillery against the Union Flag.

The Foundation described it as “unambiguously a symbol of white supremacy” and displaying it “demonstrates a clear intention to promote white supremacy and is thus hate speech”. In its heads the Ministry of Justice stated that the Union Flag was objectively the symbol of a “crime against humanity”, a symbol of colonial conquest, the display of any image of which is “akin to the use of the German swastika”, and, in turn, amounts to a “visceral propagation of racial supremacy of white people over black people and an incitement to cause harm”.

NB hate speech hearing in Supreme Court of Appeal on Wednesday - Afriforum appeal against ruling of Mojapelo DJP that gratuitous displays of the #ApartheidFlag constitute hate speech. We act for @SAHRCommission opposing Afriforum appeal. @NelsonMandela foundation also opposing.

— Dario Milo (@Dariomilo) May 9, 2022

In its submission to the court the SAHRC described the old flag as a symbol and “icon of apartheid” which represents “hate, pain and trauma” and an “evocative symbol of repression, authoritarianism and racial hatred,” the public display of which “can only plausibly and reasonably be construed as a means of asserting one’s affinity with, enforcement of and mourning for the apartheid regime.”

This case has attracted relatively little interest and attention. Most South Africans have far more pressing material concerns. And given that the vast majority of white South Africans neither display the flag, nor are particularly interested in seeing it displayed, the question sometimes put to AfriForum on social media is, “why are you even bothering to contest this?”

The Nelson Mandela Foundation & Co.’s war against the Union Flag nonetheless deserves greater critical scrutiny than it has received. Apart from their whole casus belli being contrived and built upon largely fraudulent foundations, the whole historical premise of the case is open to question, as will be explained below. And the implications of what the Foundation is seeking to achieve have not been fully grasped either.

***

Following the National Party’s victory over the South African Party (SAP) of Jan Smuts in the 1924 elections, Barry Hertzog had formed and led a coalition government made up of the NP and the South African Labour Party, a party representing (mainly) the English working class.

In his capacity as the new Minister of the Interior DF Malan had successfully moved to replace Dutch with Afrikaans as one of the official languages of South Africa. He also launched an initiative for the country to adopt its own national flag. The de facto official flag of the Union of South Africa being, up until that point, a Union Jack placed top left on a red background (the Red Ensign) with the country’s coat of arms in the middle.

The flag settled on was the Prince’s Flag which had been flown over the Castle of Good Hope under the Dutch East India Company, and on which the flag of New York state is also based. This attempt to replace the Union Jack caused an outcry among British jingoes in the SAP. The controversy reopened old wounds from the South African War and would take years to resolve.

A compromise was eventually reached between Herzog and Smuts whereby the new flag would incorporate the Union Jack alongside the flags of the old Boer republics, in the centre. The Union Jack itself would also be flown alongside the new flag in most official settings. Malan had wanted a “clean” flag, one that did not incorporate these old symbols, and he vehemently opposed these compromises, but he was eventually overruled in cabinet, and the new Union Flag was inaugurated in May 1928.[1]

After Herzog and Smuts had fused their two parties into the United South African Nationalist Party (the United Party) Malan had broken away to form the Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party. This was essentially a combination of the bulk of the Cape National Party and hardcore Republican elements in the Transvaal, Natal, and the Orange Free State.

The Fusion government was ended in September 1939, after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, when a majority of MPs rejected Prime Minister Herzog’s policy of neutrality and voted in favour of breaking off relations with Germany. As Prime Minister, Jan Smuts would take South Africa into war against Germany and then Italy. Herzog and his supporters re-joined Malan to form the Herenigde Nasionale Party in January 1940, but the following year Herzog broke away again to form the Afrikaner Party.

During the war South African volunteers would take part in the liberation of Ethiopia from the Italians and of Madagascar from the Vichy French. After the “disgrace” of the surrender at Tobruk, South African forces would redeem themselves in the first and second battles of El Alamein between July and November 1942. Allied victory in North Africa, it is worth noting, saved the Jews of Palestine and elsewhere in the Middle East from systematic mass murder by SS Einsatzgruppen aided by Arab nationalist irregulars.

South African troops would also participate in the offensive that expelled Axis troops from North Africa and in the subsequent Italian campaign. South African Airforce reconnaissance planes, flying from Italy, were the first to photograph Auschwitz. The SAAF also flew sorties to supply the Polish Home Guard during the Warsaw Uprising. Altogether some 200 000 uniformed South Africans took part in the war, of whom 135 000 were white South Africans, with 70 000 black and Coloured servicemen serving in auxiliary roles. Just under ten thousand South Africans were killed in the war.

DF Malan sought to keep the HNP’s strident opposition to South Africa’s involvement in the war within strictly constitutional bounds. Elements within the Afrikaner nationalist movement fell under the spell of National Socialism embracing, at various times, its virulent anti-Semitism and rejection of Western democracy.

Malan for his part would initially seek to temporise with these elements, particularly as they found organisational form in the New Order and Ossewa Brandwag (OB), before moving to outmanoeuvre and defeat them politically from 1941 onwards.

Among those who joined the OB, and expressed pro-National Socialist sentiments, were Piet Meyer, the deputy secretary of the Broederbond, and a young John Vorster, who was detained for two years without trial as Prisoner 2229/2 in Bungalow 48 at the Koffiefontein internment camp in the Orange Free State. Throughout his subsequent political career, The New York Times would refer to Vorster as a “wartime Nazi supporter”.

***

Three years after the war ended in the defeat of the Axis Powers, the Nationalist Party was elected to power on its apartheid platform. It won 70 out of 153 seats with 37,7% of the vote versus the United Party’s 65 seats, won with 49,2% of the vote. The NP was only able to secure a majority in parliament and form a government with the support of the Afrikaner Party, which had secured nine seats in the House of Assembly with 4% of the vote.

The new HNP Minister of Defence, Frans Erasmus, set about clipping the wings of the Union Defence Force. He discharged or side-lined many top-class officers with distinguished war records (such as Evered Poole), and changed uniforms and emblems.[2] By contrast many of those who had overtly aligned themselves with Germany’s National Socialists in the 1930s and 1940s were rehabilitated and appointed to prominent positions within the Afrikaner nationalist movement. In 1950 Louis Weichardt, the founder of the Greyshirts in 1933, was appointed provincial organiser for the Nationalist Party in Natal.

The NP also moved to put into effect their apartheid manifesto and shore up their government’s precarious majority in parliament in the process, by setting out to disenfranchise Coloured voters in the Cape through the Separate Representation of Voters Bill, in violation of the entrenched clauses of the 1910 constitution.

There was great unhappiness among many ex-servicemen at these developments. The lightning rod which transformed this brooding discontent into a mass political movement was provided by an event organised by the Springbok Legion in April 1951, in which striking symbolic use was made of the Union Flag.

The Springbok Legion had been founded during the war as a servicemen’s trade union type organisation, open to all races, in 1941. Its programme of getting “a square deal for soldiers” had seen it attract a membership of 55 200 by the end of 1944.

From the start members of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) had played influential roles in the organisation and its civilian partner organisation, the Home Front League.[3] Among the members of the latter were Bram Fischer, Vernon Berrange and Ruth First. At the time pro-Communists and non-Communists in the Springbok Legion shared an overriding common goal, namely victory of the Allied Powers, and so the political differences between them remained latent.

After the war ended the membership of the Legion dwindled with many white ex-servicemen regarding its pro-Communist orientation, especially in the Cold War context, as an anathema. One of the organisation’s founder members, Vic Clapham, resigned from the organisation’s Executive in 1947 due to the increasing dominance by pro-Communists, and had also allowed his membership to lapse. [4]

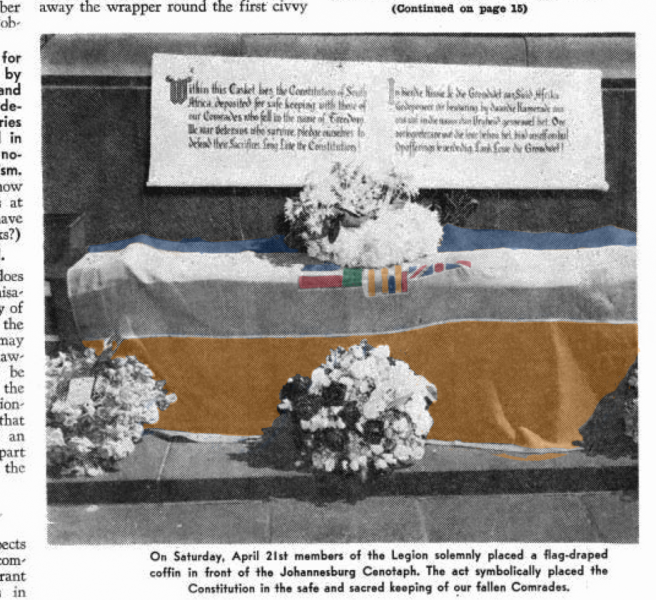

On 21st April 1951 the Legion held a ceremony at the cenotaph near the Johannesburg City Hall. The Johannesburg branch committee, to which Joe Slovo had recently been elected, would presumably have played an instrumental role in organising this event. A coffin, draped in a Union Flag, was laid in front of the cenotaph. Above it was placed a notice in both English and Afrikaans which read:

“Within this Casket lies the Constitution of South Africa, deposited for safe keeping with those of our Comrades who fell in the name of Freedom. We war veterans who served, pledged ourselves to defend their Sacrifice. Long live the Constitution!”

A partly colourised image of the flag draped coffin laid before the cenotaph in Johannesburg. It appeared in Fighting Talk: Organ of the Springbok Legion, May 1951

This act attracted some criticism, with one person writing to the Legion to complain that this was an act that desecrated the memory of the fallen “with politics”. In reply, the organisation’s National Secretary, the actor, theatre director and war veteran Cecil Williams wrote:

“The Cenotaph is our memorial to 10,000 South African men and women who gave their lives in the most momentous struggle of our times – the struggle to rid the world of the bestial Fascist system and to secure the democratic way of life. Enlisting was the most ‘political’ action servicemen ever performed. Ex-service men have a moral obligation to carry on the same struggle to achieve the ideals for which the war was fought. Men and women in the Springbok Legion accept that obligation… We do not desecrate the memory of the fallen. Because we honour their memory and their sacrifices, we carry on their struggle where they had to leave off.”

The general response was positive, with the event itself attracting a crowd of 3 000. Cecil Williams and the Legion’s General Secretary, Jack Hodgson, approached Clapham, now an organiser for the United Party, suggesting the mobilisation of ex-servicemen against The Separate Representation of Voters Bill.

Clapham had agreed but to maintain some political distance between this initiative, the UP, and the Legion, a War Veterans Action Committee (WVAC) was established, which would be chaired by Major Louis Kane-Berman, and on which the Battle of Britain fighter ace Group Captain A.G. “Sailor” Malan had agreed to serve. Harry Schwarz was also a member.

The real work was done by the thirty-member ad hoc Johannesburg WVAC committee, also chaired by Kane-Berman, and which included Williams, Hodgson, Pieter Beyleveld, and number of other current and former members of the Springbok Legion’s National Executive Committee.

On the 4th May a torchlit march through the streets of Johannesburg was held, with some 5 000 ex-servicemen and 10 000 other people taking part in the meeting on the steps of City Hall. Among those who addressed the meeting was Sailor Malan, South African War veteran Dolf de la Rey, and Leo Lovell, the UP MP for Benoni, and a member of the Springbok Legion’s national executive.[5]

In his speech, Lovell noted that while South African volunteers were battling the “Nazi hordes” up North there was a “Fifth column way back in the Union who hated the things we loved and fought for, and who agitated for the things our foreign enemies desired. Now they are in the seats of power. Are we surprised at what they are busy doing?”[6]

The gathering adopted four resolutions which inter alia condemned the action of the present Government “in proposing to violate the spirit of the Constitution” and pledged “to take every constitutional step in the interests of our country to enforce an immediate General Election.”

Under the heading “SA War Veterans Plan Steel Commando Drive on Cape Town” the Rand Daily Mail reported on 12th May that a “torchlight march on Parliament headed by a Steel Commando of wartime ‘jeeps’ from all parts of the Union will take place on the night of May 28 and the four resolutions passed at last Friday’s great ‘Freedom March’ in Johannesburg will be presented to selected Members of Parliament.”

The first jeep would leave Pretoria on the night of 23rd May and would then link up with a second vehicle at Johannesburg City Hall. Jeeps would also set out from Durban and East London and, travelling by three different routes, they would pass through fourteen major centres in the Union. The League’s publication Fighting Talk described this as “Operation, Torch Commando”. Again, much of the organisational work was done by members of the Springbok Legion with Cecil Williams serving as “adjutant”.

On the evening of 23rd May 1951, a crowd of two thousand people gathered to watch what the Rand Daily Mail also now termed the “torch commando”, consisting of two jeeps and eleven other cars, leaving for Cape Town, with “Oom” Dolf De la Rey in the first jeep, and Sailor Malan in the second. Addressing the crowd Malan stated:

“We have stood silent for three years and have watched this power-drunk Government controlled by a secret, sinister organisation [the Broederbond] assail our liberties on by one – some by stealth, and all with cynical Fascist arrogance. We will no longer stand for a government which, in the last war, openly supported our enemies – a set of politicians who are now setting up in this country the same type of government which our enemies would have established had they been the victors.”

The vehicles themselves carried Union Flags, flaming torch symbols, “no surrender” slogans and placards showing where they had come from. The Reverend Father Trevor Huddleston wished the commando “God speed” before they left.[7] In the British Movietone newsreel from the time (view below) one can see that the jeeps, and the other vehicles that accompanied them, marked with the “flaming torch” symbol and flying Union Flags.

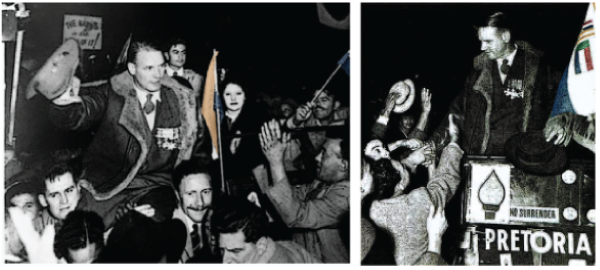

On its arrival in Cape Town the torch commando was welcomed by a huge crowd. The Rand Daily Mail reporter, who was embedded in the convoy, described the experience of riding with the “Torch Commando tonight through cheering multitudes” as being akin to “driving into Brussels again with the Army of Liberation”.

“Half a mile before it reached Cape Town’s Grand Parade the Commando was slowly edging through a narrow lane of wildly excited people, who reached into the cars to slap the men on the back and shake their hands. A woman looked into the Johannesburg vehicles with tears streaming down her face and said: ‘God bless you.’

“From this car we could sometimes see ‘Oom’ Dolf standing in the leading jeep and ‘Sailor’ Malan in the second wearing his old Air Force sheepskin jacket. The cheering never stopped. Two hundred yards from the meeting place the cars were jammed, and the crews had to leave their vehicles and fight their way to the platform from which it was impossible to see where the vast throngs ended. Far away in the distance torches still flickered.”

After the event the police described the crowd as the “biggest ever to gather on the Grand Parade”, although it was not possible to put a number to it. On the Rand Daily Mail’s frontpage the next day was a picture of Sailor Malan on his triumphant arrival, wearing his air force jacket and war medals, and being carried shoulder high by the crowd. One can see one Union Flag flying from the jeep and another being waved by a member of the crowd.

Two partly colourised photos of Sailor Malan's arrival in Cape Town with the Steel/Torch commando. A slightly fuller version of the picture on the left appeared on the front page of the Rand Daily Mail, Tuesday, 29th May 1951

Two of the key symbols employed by members of the Springbok Legion to mobilise ex-servicemen into opposition to the Nationalist Party were thus the torch, representing freedom, and the Union Flag, under which South African volunteers had fought against the “Nazi hordes” in the Second World War.

The culmination of “operation, torch commando” came on 28th May as the main meeting on the Grand Parade ended and a crowd of thousands, allegedly spurred on by Springbok Legion members, sought to force their way towards parliament. A melee ensued after the protesters attacked the police and the police launched numerous baton charges in return, with over 160 people, including 17 policemen, injured in the clashes outside the House of Parliament.[8]

Although this violence was blamed by the Rand Daily Mail on opportunistic misbehaviour by “disreputable” elements from District Six, the subsequent literature has tended to the view that this represented a failed attempt to force the Nationalist Party out of government. In his study Michael Fridjhon noted, “There seems to be little reason to doubt that by this stage some members of the Legion were prepared to gamble everything on an insurrection.”

In response to these events, and Nationalist government’s attacks on the “Communists” of the Springbok Legion, the Johannesburg WVAC took fright and voted on 7th June 1951 by fifteen votes to eleven to purge “prominent members and paid officials of the Springbok Legion” from the committee. This may well have saved the Torch Commando as an organisation from communist subversion, but it was at the price of losing the fiercely idealistic, brilliantly creative and highly effective left-wing activists and organisers who had played a leading role in conjuring the movement into existence in the first place.[9]

The pro-Communists of the Legion would, the following year, go on to help secretly re-establish the South African Communist Party and found the South African Congress of Democrats. Beyleveld was elected the COD’s first president, and Hodgson its secretary. Slovo was elected on to its NEC. Though a leading mover behind its formation, Cecil Williams was prevented from playing any formal role in the organisation by a banning order issued by the recently appointed Minister of Justice, John Vorster.

Legionnaires would, under the auspices of the COD, help organise the Congress of the People in Kliptown and write the Freedom Charter (Rusty Bernstein). They would also go on to play a central role in the liberation movement’s shift to armed struggle and the formation of Umkhonto we Sizwe between 1960 and 1961.

In his somewhat misleading account in Long Walk to Freedom Nelson Mandela recounts how, on the formation of MK, he “immediately recruited Joe Slovo and along with Walter Sisulu we formed the High Command with myself as chairman. Through Joe, I enlisted the efforts of white Communist Party members who had resolved on a course of violence and had already executed acts of sabotage such as cutting government telephone and communication lines. We recruited Jack Hodgson, who had fought in the Second World War and was a member of the Springbok Legion, and Rusty Bernstein, both party members. Jack became our first demolition expert.”

Cecil Williams also joined MK and worked closely with Mandela while he was operating underground. Williams was behind the wheel when he and Mandela were intercepted and arrested by the police outside Howick while on the way back from Durban in August 1962.

***

If the most radical white opponents of the Nationalist Party had in April and May 1951 made heavy use of the Union Flag as an “anti-Fascist” symbol, what was the attitude to it of their political adversaries?

The forced inclusion of the Union Jack at the centre of the Union Flag had always rankled with Afrikaner nationalists. Given that they had opposed South African involvement in the Second World War, and some had actively fought against it, they had also not formed the emotional connection to the flag that members of the Springbok Legion and other war veterans had during the conflict.

The initial priority of the Nationalist Party government though was removing the Union Jack itself as one of the official flags of the Union of South Africa. This flag, as one letter writer to the Rand Daily Mail described it in the 1950s, “has been, and always will remain, a symbol of defeat and humiliation to more than sixty per cent of the White population of the Union. Racial peace is impossible while it is slapped in the face of our people, bringing back memories which are best forgotten.”[10]

The 1957 Flag Amendment Bill stated that the Union Flag should be the only national flag. In his speech to the senate on the bill Vause Raw, a senator for the United Party and war veteran, recognised that this was “not only an attack on the Union Jack as a symbol of the Commonwealth, but a threat to the Union Flag.”

He observed that “Nationalist speakers regarded the bill as pulling down the flag of the conqueror” but if there “was so much hatred towards the Union Jack, then the next step would be to remove it from the Union Flag.”[11] In this period NP politicians would occasionally express their desire for a “clean” flag, and when pressed, NP leaders would studiously avoid giving a commitment that the Union Flag would not be changed.

In 1960 Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd announced that a referendum was to be held on 5th October asking the whites-only electorate whether they were in favour of a Republic. A majority “yes” vote was by no means guaranteed and the NP sought to win across English-speakers and other UP voters on this issue.

Sentiment among the most avid Afrikaner republicans was strongly in favour of changing the flag, should a Republic be achieved. When Verwoerd arrived in Bloemfontein to open a special congress of the National Party on the matter – at which he made an appeal for the support of English-speaking voters – he was greeted at the airport by supporters in cars “displaying the Union flag, but with the Union Jack obliterated.” In its place was “a green ‘R’ which stands for Republic.”

In its report on this incident the Rand Daily Mail noted that Verwoerd has “persistently avoided giving an undertaking in Parliament that the National Party stands by the present design of the Union Flag. It is well known that Nationalist extremists cannot stand the sight of the miniature Union Jack in South Africa’s flag.”[12] In an editorial the newspaper noted:

“The centrepiece of the Union Flag consists of the old Free State Flag, the Transvaal Vierkleur, and the Union Jack. Because of the presence of the Union Jack the Nationalists have never liked this design. One is entitled to ask if they were demonstrating in Bloemfontein how, if the republic should come about, they intend getting the ‘clean flag’ they have talked about for so long.

“The Union Jack occupies less than one-twentieth of the surface of the Union Flag, but even that, it seems may not be tolerated in the republic. So much for the regard the republicans claim there will be for the sentiments and traditions of English-speaking South Africans.”

The following month the Minister of Defence Jim Fouché was forced to give a hard assurance, at a pro-Republic rally in Pretoria, that the flag would not be changed if South Africa became a republic. This was in response to questioners who demanded variously a “true republican flag without the Union Jack” or the removal of the “Khaki blanket”. One questioner said that it “grieved” him to see the Union Jack on the national flag. “It is the flag which destroyed our mothers and children in the concentration camps, and we must do away with it.” In reply Fouché said white unity would need to start developing the day after the referendum and it would be senseless to start a new struggle – by seeking to remove the Union Jack – which might continue for years.[13]

***

The Union Flag was thus initially left unmolested after South Africa became a republic on 31st May 1961, following the narrow (52% to 48%) victory of the “yes” vote in October 1960. By 1966 Verwoerd had decided that the situation had sufficiently settled politically for the flag to finally be changed. Shortly before he was assassinated on 6th September 1966, he gave Dr Piet Meyer, chairman of both the Broederbond and the South African Broadcasting Corporation, permission for the nationalist movement to set about campaigning for a new republican flag.

In August the following year the campaign for a new flag was publicly set in motion at the National Party congress in Natal with delegates voting overwhelmingly (125 to 1) in favour of a new flag. Prime Minister John Vorster hinted that he would be very much in favour of this. “Let me say, as an old Cape man, that I am not married to the Union Jack in the Republican Flag. If the people of South Africa want a new flag, they will get a new flag. There is not the slightest doubt about this.”

This was a matter that would however have to be discussed by the other NP provincial congresses, Vorster noted, but if this motion was carried by a similarly overwhelming majority there as well, then “it will not only be my duty, but my pleasure, to take the matter to the federal council of the National Party.”

Once again, the Rand Daily Mail spoke against this plan in an editorial. “The absence of any storm of indignation should not be taken as approval” for such a move, it said. “The great majority of English-speaking people would prefer to keep the flag as it is and if this preference is expressed in murmurs, it is because of the resignation, helplessness and withdrawal that characterises the English-speaking outlook these days. This is not a healthy attitude and, if they were wise, the Nationalists would endeavour to dispel it rather than reinforce it.”[14]

In 1968 the NP’s Federal Council proceeded to endorse the need for a new republican flag in principle but left the timing of the change-over to Vorster, as the leader of the party. In early September 1968 the Cape Congress of the NP endorsed this approach.[15] The following week Vorster announced his decision on this matter to a crowd of 3 000 at the Transvaal National Party congress at the Pretoria City Hall.

In his speech he noted that the desire for a new flag had been expressed across the nationalist movement. He had thus had to ask himself: “Is the time to do it now? And I say yes. The time has come!” The crowd stood and cheered in what the Rand Daily Mail described as a “standing, almost frenzied ovation”. Vorster then added: “The way you have received this leaves me with no doubt.”

He told the congress that this new flag would be a flag for White South Africa, as the Transkei already had its own flag, and the other homelands would get their own flags at the appropriate stage as well. He also said that the commission would be appointed to ensure that the country got the right flag.

In his response the leader of the official opposition, Sir De Villiers Graaff, said that the United Party would cooperate in the process, but that they would prefer to keep the old flag. The Progressive Party was more outspoken. In a press statement the party’s leader Dr Jan Steytler questioned the “wisdom” of this move, saying it would do more harm than good, and was likely to be highly divisive.

“Instead of being the powerful unifying factor which it should be, this proposed flag might be a symbol of division and indeed enmity, particularly as the majority of Africans are going to be living permanently in the White Areas and not in the so-called ‘homelands.’” Furthermore, since the Indian and Coloured people would have no pretence to homelands, “the new flag might be interpreted as a symbol of their rejection by the Whites.”[16]

Vorster disregarded such warnings and pressed ahead. At the end of the month, he appointed a commission of inquiry which would report to parliament on the new flag. A Broederbond member, Justice JF Marais of the Transvaal Bench, would head the commission, and the Chairmen of the FAK and the 1820 Settlers’ Association, would also be invited to serve on it. Two experts on heraldry would also be appointed, as would representatives of the NP and the UP.

The Rand Daily Mail article on Prime Minister John Vorster's announcement of a new flag as it appeared on the front page of the newspaper 12th September 1968

The intention was that the new flag would be inaugurated on the tenth anniversary of the Republic on 31st May 1971. In early February 1970 the Rand Daily Mail reported that as part of the planned festivities the Rapportryers, a junior arm of the Broederbond, would carry sealed versions of the new SA flags and a message from the State President by horseback to the provincial capitals, as well as Windhoek. In August 1970 a circular from the Transvaal Education Department informed parents that the “new flag” to be unfurled on 31st May the following year.

The festival organisers disclosed in January 1971 that, much to their puzzlement, they were not going to receive a new flag after all. They did not know why this was the case and had just been told that it was the old flag that would be unfurled by the State President. The Rand Daily Mail noted in its report that following the 1968 announcements “the issue of a new flag for South Africa has been surrounded in mystery. Calls to publicise designs and possible colours of a new flag have gone unheeded and Members of Parliament even questioned whether the proposed commission had ever sat to carry out its task.”

In July 1971 Justice Marais stated that the shelving of the new flag project “had occurred after a difficulty, the nature of which he was not free to divulge, which was seen by the Prime Minister as insurmountable.”

***

This was not however the end of the matter, as sentiment in the Afrikaner nationalist movement remained in favour of a change of flag. A Transvaal NP Congress resolution in September 1972 asked the government to give “earnest attention” to the issue.

In May 1979 “a secret nationwide campaign to replace the present flag”, was reported on in the press, with a “highly confidential circular calling for the removal of the Union Jack from the flag” apparently being “circulated to thousands of leading Afrikaners, including Cabinet Ministers.” The Rand Daily Mail reported that Prime Minister PW Botha had “left the door open for a change in the South African flag. Mr Botha said a Parliamentary Select Committee was considering changes in the country’s constitution and this automatically included the flag.”

In June 1981 the Rand Daily Mail reported that Professor Carel Boshoff, the chairman of the Broederbond, had confirmed that he intended to put forward a proposal to the President’s Council recommending a new South African flag. This was on the lines of the proposal he and Eugene Berg had drafted two years previously, and which had called for the removal of the three small flags from the white centre.

In his response Harry Schwartz, now a Progressive Federal Party MP, said he “would never accept a Broederbond-inspired flag.” He also stated that “a decision about a new flag should come about at the same time that a new constitutional dispensation comes about for all the peoples of South Africa”.

A similar point was made by Nthato Motlana, chairman of Soweto’s Committee of Ten, who told the newspaper “We must drop this nonsense that there are only white people running this country. Before adopting a new flag, there must be thorough consultation among all South Africans. Only by mutual consensus can we reach an agreement on the shape and colours of the South African flag. We certainly don’t want a ‘Broeder flag.’”

The Rand Daily Mail headed its story on this negative political reaction to the proposal “Leaders give thumbs down to the ‘Broeder’ flag design”.

In an editorial on this matter, as well as the recent controversy around university students burning the national flag, the Rand Daily Mail caustically noted that “the cursory respect which the Broederbond pays to the national flag which it frankly wants to scrap is forgotten as the Government rages about flag burning by a handful of silly students.” As for the flag burners’ actions, it observed: “Those students have, of course, made it all too easy. To burn a flag can have only one purpose: to provoke those who hold it dear, and the people who hold the South African flag most dear, ironically, are not the Nationalists but those who fought under it in World War II.”

Yet again, this Broederbond proposal would come to naught, and a flag change was not part of the implementation of the 1983 Constitution. By the late 1970s much of the NP leadership had come around to recognising that apartheid and separate development was a dead end, and they had already publicly committed to ending several of the most odious features of that system.

By 1983 conservative Afrikaner elements had broken away to form the Conservative Party. The NP was thus increasingly dependent on the support of mostly English-speaking former United Party voters to hold onto its electoral majority.

It was also perhaps recognised that such a fraught symbolic project as changing the national flag should await the finalisation of a constitutional dispensation inclusive of all South Africans. This is indeed what ultimately transpired. The genius of the post-1994 South African national flag is that it somehow managed to combine the primary flags of African nationalism (the ANC flag) and Afrikaner republicanism (the ZAR one) into one unifying national symbol.

***

In the Whig Interpretation of History Herbert Butterfield wrote that when “we organize our general history by reference to the present we are producing what is really a gigantic optical illusion”. Viewed from the present the Union Flag may well appear to be the “apartheid flag”, but this is ahistorical. This was certainly not the perception of the ex-servicemen like Cecil Williams and other Springbok Legion members when they mobilised against the nationalists in the early 1950s, of opposition politicians, or indeed of a publication like the Rand Daily Mail.

It is not just that the adoption of the flag predated the introduction of apartheid proper by two decades, but that through much of the NP’s four decades in power Afrikaner nationalists had diligently plotted away to eventually replace it with a new and “clean” republican flag. Had John Vorster and Piet Meyer succeeded in their original plans the flag that would have been introduced in 1971 could certainly have been described as an “apartheid flag” as this was explicitly intended to be the flag of “White South Africa” alone in terms of their ideology of separate development. For reasons that remain obscure this plan was never pushed through.

As it was, it was well understood into the early 1980s that many in the NP and Broederbond detested the flag, as it stood, and that those who had the greatest emotional bond to it were veterans of the war against Nazi Germany.

One of lessons of the history recounted above is that a country’s leaders need to tread softly when it comes national symbols. In a divided society these can have radically different meanings to different peoples. The presence of the “Union Jack” at the heart of the Union Flag was offensive to many Afrikaners, who regarded it as a symbol of their people’s immense suffering at the hands of British imperialism at its jingoistic worst. Yet its removal from the flag would have been regarded by white English-speakers as symbolic of their marginalisation under Afrikaner nationalist rule and caused deep hurt and offence.

Nelson Mandela for one understood such sensitivities implicitly. During a critical period of the transition from white-minority to black-majority rule, when the country was close to civil war, he dealt with potentially explosive symbolic questions with enormous grace and wisdom. This legacy endures in the current national flag, the national anthem, and the retention of the Springbok as the emblem of the national rugby team. The replacement of the old flag with the new one was a much less fraught matter, as those from the Afrikaner republican tradition, particularly in the Transvaal, never had much love for it in the first place. Indeed, most white South Africans were, for opposing reasons, probably more content with the new flag than they had been with the old one.

Equally, when it comes to try and change or (as in this matter) “criminalise” national symbols a country’s leaders are well advised to leave an imperfect but adequate status quo well alone. In this case many black South Africans understandably view the old flag in much the way that many Afrikaners once saw the Union Jack – as symbolic of their degradation and humiliation over 80 years of increasingly repressive white rule in South Africa. White South Africans are generally sensitive to these perceptions and for this and other reasons the use of the old flag has become vanishingly rare.

The Union Flag was the national flag for the last 66 out of 88 years of white political domination over the Union and then Republic of South Africa, with the Union Jack being the or an official flag for the first 47 years. The point that is being forgotten in this debate is that while it can certainly be seen as a symbol of all the wrongs, injustices, and state crimes committed during that period, it is equally a symbol of all that was achieved through that time, and much that was honourable and good.

The Union Flag was thus the flag under which the legislative edifice of apartheid was constructed, the flag under which the white opposition mobilised against that project (most strikingly in the case of the Torch Commando), and the flag under which it was systematically dismantled over the last decade of white rule.

It is the flag under which South African volunteers fought Nazi Germany and the Italian Fascists in World War Two, the flag under which the country’s soldiers battled the Soviet Union and its proxies to a stalemate in Angola in the late 1980s, and the flag under which many unspeakable murders were committed by the covert units of the police and military, especially in the desperate, dying days of white rule. It is equally the flag under which members of the National Intelligence Service (and others) put their lives on the line to investigate those crimes and bring the culprits to justice.

What the Nelson Mandela Foundation, the ANC government, and the SAHRC are seeking to do though is to impose a single meaning on the Union Flag, and the worst one that it is possible for any human being to imagine. In doing so they are, for one, desecrating the memories of those soldiers who risked and sacrificed their lives in the war against Nazi Germany. This is particularly unforgivable in the case of the Foundation given how many of Nelson Mandela’s old comrades had been members of the Springbok Legion.

Beyond this they are by imposing this one meaning, a symbolic level, effectively seeking to erase the contribution that this once powerful, but now powerless and beleaguered racial minority, made to the building and developing of South Africa before 1994.

The message that this sends, at a time of already high emigration, is that the continued presence of the white minority in the country is one to be tolerated perhaps, but never to be valued.

What a pity it is that the Nelson Mandela Foundation - an organisation founded by a man renowned as a "great and good and graceful leader" - chose to take up such a petty and spiteful cause.

[1] Lindie Koorts, DF Malan and the Rise of Afrikaner Nationalism, Tafelberg: Cape Town, 2014

[2] “Erasmus must go, says Ross”, Rand Daily Mail, 6 September 1958

[3] Neil Roos, Ordinary Springboks: White Servicemen and Social Justice in South Africa, 1939-1961, Routledge London, 2018 (first published 2005 by Ashgate Publishing.)

[4] Barry White, The South African Parliamentary Opposition 1948-1953, University of Natal, DPhil Dissertation, 1989

[5] The speech was published verbatim in the May 1951 edition of Fighting Talk

[6] Fighting Talk, May 1951

[7] “Torch Commando Leaves Rand in Protest Drive”, Rand Daily Mail, 24 May 1951

[8] Roy Isacowitz, Telling People What They Don’t Want to Hear: A Liberal Life Under Apartheid, Kibbitzer Books, Kindle Edition, 2020

[9] Of the non-Communist leaders Jock Isacowitz, who had resigned from the CPSA in 1946 and served as Springbok Legion national chairman until April 1951, would go on to help found the Liberal Party in 1953.

[10] F J van Straaten, letter, Rand Daily Mail, 22 July 1958

[11] Rand Daily Mail, 14 March 1957

[12] Rand Daily Mail, 30 August 1960

[13] Rand Daily Mail, 10 September 1960

[14] Rand Daily Mail, 17 August 1967

[15] Rand Daily Mail 5 September 1968

[16] Rand Daily Mail, 23 September 1968